Hammering away at patient ID error

| Hammering away at patient ID error |

|

|

|

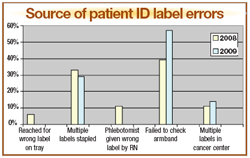

April 2010 Karen Titus Patient identification isn’t a game. But at Nebraska Methodist Hospital, Omaha, ID efforts bear an uncanny resemblance to Rock-Paper-Scissors. Call it stapler-highlighter-human nature. These are the more prominent elements that have helped and hindered phlebotomy team leader Diane Wolff, CLA(ASCP), as she and her colleagues have worked to reduce patient ID and specimen labeling errors at Methodist. For now, the highlighter appears to be trumping the stapler, and the phlebotomists cut their errors by more than half in 2009, versus the previous year. On the other hand, no amount of training, education, pleading, or probation seems to ever fully triumph over human nature, which oftentimes seems hell-bent on upending the best-laid schemes of phlebotomy team leaders as well as mice and men. The numbers are easy to follow. For 2009, the second year for which these QA data were collected, seven patient ID errors were logged, down from 18 in 2008. Wolff breaks down the major sources of error for 2009 into three categories:

These represent a reversal from 2008, when more errors were made by experienced staff. The numbers do not tell the whole story, however, and as Wolff explains the Methodist program, her stories often take on the specifics of a word problem in math. The current efforts grew out of earlier use of the CAP Q-Track for wristband errors. As those errors diminished and were finally laid to rest by electronic wristband printing in the access center, Wolff began casting about for another quality improvement project. She already knew, based on data gathered at the start of the Q-Track effort in 2000, that phlebotomists were making patient ID errors. At the same time, a new Cerner LIS made it possible for her to track those errors, primarily by identifying sharp changes in patient lab test results. Digging deeper, Wolff found that 26 patients were drawn wrong/ misidentified from March to December 2000. Some 10 years later, disbelief still burbles up in her voice when she recalls the figure. Wolff, who spent years as a core lab technician before moving to phlebotomy team leader, was shocked. “I knew how important patient identification was,” she says. Perhaps just as unsettling was seeing that seasoned phlebotomists were the source of many of those errors. “They were becoming complacent,” she says. She immediately began sounding the alarm, telling everyone—at meetings, via regular e-mail reminders—to make sure they were checking patient identification. “It was like a mantra,” she says. In 2001, she and her colleagues also revved up what she calls an aggressive corrective action policy/performance improvement program. Any long-term staff member (that is, on the job longer than a year) who made a patient identification error was automatically suspended without pay (after an intense investigation into the incident), anywhere from a day to a week, depending on the severity of the offense. “Which made all the phlebotomists nervous, but you know what? The very next year we cut our identification errors in half,” says Wolff. Hardly shabby. “I thought we were making progress,” she says. By 2005, when the hospital changed its policy and procedures on banding patients, “We basically flat-lined on the Q-Track, and saw hardly any errors” related to armbands and patient ID. Wolff, apparently, does not enjoy sitting on her laurels. Looking for another way to improve quality, she decided to tackle patient ID errors related to phlebotomy. A main source of such error was obvious, if not easily routed—failing to identify a patient. The second major source was dealing with a putative improvement—the system’s move to preprinted bar-coded labels. What’s not to love about tightly packaged, electronic information? Nothing—until you start stapling it together. During the so-called power draws at Methodist, between 4 AM and 7 AM, the phlebotomists would be dealing with large numbers of orders. One patient could, and often did, have multiple bar codes, which the clerical staff would then staple together. Naturally, amid the flurry of printing, collating, tearing, and organizing, different patients’ labels would occasionally, accidentally, end up stapled together. And the phlebotomists weren’t always catching them. A phlebotomist might have three labels for John Smith, along with one for Dorothy Jones in the next room. “They just weren’t paying attention,” Wolff says. Banning the stapler didn’t work. “We tried that for about a month, Ohhhhh,” says Wolff, still sounding pained at the memory of those four weeks. “It was not pretty.” So she changed the process once again, turning to the highlighter pen. Before phlebotomists left for the floors to do their draws, Wolff required them to highlight the last name on every patient label that was stapled together.  It worked. And then... At the end of 2007, Wolff had another proposal for her direct supervisor: formally tracking patient ID errors by phlebotomy. A year later, they saw those aforementioned 18 errors. It takes some time to explain how those errors occurred. Each error has its own story, its own players. For example: Methodist has an outpatient draw area in its cancer center, an open room with four draw stations separated by privacy curtains. Here, between 8 AM and 4:30 PM, the three or four phlebotomists working the shift might be drawing as many as 160 patients. The labels are printed on-site; given the volume, it’s possible for the phlebotomists to accidentally pick up a wrong label. “And they didn’t catch it,” Wolff says. “Again, we made some changes,” she continues. This included more education for the phlebotomy staff in the cancer center, such as one-on-one coaching and review of incident reports. “We made them aware of how these errors were occurring, without singling anyone out,” she says. Even bigger, she says, have been the monthly coaching sessions for new staff—those employed at Methodist less than a year. Coincidentally, 2009 was a year with more than a dozen new phlebotomy hires. Wolff and her phlebotomy training coordinator (and medical technology instructor), Kathleen Zadina, PBT (ASCP), used the personnel shift to think about fresh ways to indoctrinate new staff to the importance of patient ID. While new staff were taught to identify patients, they didn’t always appreciate how risky it was not to. Says Zadina: “It hasn’t dawned on them they’re dealing with patients’ lives.” Telling them isn’t enough. Zadina spends plenty of time with new hires giving them examples, including the case of two Michigan teenage girls who were involved in a traffic accident. One died; the other lived. Through a series of mistakes and omissions, the girls were misidentified, and for more than a month the surviving teen was assumed to be the other girl. Zadina’s message to her trainees: No one ever asked the girl her name. “Don’t assume anything,” she says. 2009 saw the drop from 18 errors to seven, and Wolff credits the shift in educational emphasis. In the first two quarters, almost all the errors were made by new staff. So in mid-summer, Wolff and Zadina began those monthly meetings, reiterating the risks of patient ID failure. They also reminded new hires that they were moving out of their probationary period. Now, errors (after an investigation) would mean an automatic suspension. (At a second offense, the phlebotomist is placed under a performance review, and he or she is monitored while doing collections. At a third offense, the employee is terminated.) Wolff and Zadina have also traded a little anonymity for more transparency. In years past, Wolff says, she would keep errors confidential between her and the phlebotomists who committed them. Now, without naming names, she and Zadina discuss any and all errors that occur at the monthly meetings, driving home, once again, that errors aren’t acceptable. Wolff sounds a bit like Thomas Gradgrind, the notorious headmaster in Dickens’ Hard Times, who liked to chant “Fact, fact, fact!” at his students. Wolff, with far more humor and her eyes on a worthy prize, says, “We want it to be safe, we want it to be safe, we want it to be safe. Safe, safe, safe, safe.” Over the years, Wolff has also learned to account for the sometimes inscrutable behavior of human beings, some of whom cannot be budged from their planetary work habits. “When I first started tracking these errors, I was disappointed, and surprised, that my longtime people were making them,” says Wolff. “They know full well that patient ID is the most important part of their process.” Wolff suspects they simply grow complacent. A phlebotomist on the overnight staff typically works seven days on, seven days off; over the course of the week, he or she might work the same two or three floors. That leads to familiarity, which in this case breeds not contempt but contentedness. “They get to know the patient, and all of a sudden they don’t follow the process, which is: Walk in. Hi, I’m here from the lab to draw your blood.’ Look at the armband and ask them to state their name,” Wolff says. Every step is finely tuned. Phlebotomists need to ask patients to state their names, rather than ask patients if they are, for example, Jack Smith. It’s a subtle difference. And it’s a process change Wolff’s older phlebotomists have had trouble adopting. “They have their own style, their own bedside manner,” she says. “It’s been hard for them to change.”

Drill down deep enough, and you hit the bedrock of human nature. Zadina, who says three phlebotomists have been fired over a nine-year period, doesn’t have any easy explanations. One phlebotomist, since terminated, would leave the labels at patients’ doors, memorize them (“as far as he was concerned,” says Zadina), proceed with the draw, then label the tubes outside the room, without any direct comparison between labels and patients. Why was he functioning (so to speak) this way? “I have no idea,” says Zadina. Another phlebotomist, also fired, never managed to learn the process. “We counseled her and counseled her. I don’t know why she couldn’t get it,” Zadina says. Yet she’s sympathetic to the interruptions that can disrupt a phlebotomist’s meticulous routine. A physician may walk in and give additional orders just as the phlebotomist is preparing to ID the patient. “Well, you go write that down. And then you go back, and your tourniquet is already there, and you assume that’s the point you’re at in the process,” says Zadina. But the patient has not been identified. She’s trying to adjust for such distractions by adding yet another element to phlebotomists’ training. New phlebotomists are learning to check with patients after everything has been labeled, correlating their armbands with every tube of blood. “If you missed it the first time, you caught it the second time,” Zadina says. So far, this extra step seems to be working. In 2010, Wolff hopes to see the number of ID errors drop by half again. If that happens, she would consider calling their efforts a success and start using the numbers as a maintenance monitor. Beyond that, she’s looking ahead to a specimen integrity project. But, ever-vigilant, she knows it’s never possible to fully let down her guard. She tells the story of her father’s recent visit to a doctor’s office, where she watched a health care provider draw his blood, then set the unmarked tubes on the counter while she left to get more paperwork. Wolff says she fought off the urge to get up and write her father’s name on the tubes herself. “At one point my dad looked at me and said, ‘What’s the matter? Why are you staring so hard at those tubes?’ I told him, ‘They don’t have a label on them.’” Her dad assured her the provider would indeed mark the tubes when she returned, but Wolff made a vow of her own. “I said, ‘I am not going to let her leave this room, Dad, until she does that.’” Karen Titus is CAP TODAY contributing editor and co-managing editor. |