Karen Lusky

January 2020—A molecular oncology tumor board session at CAP19 explored a case of cancer of unknown primary, presented by medical oncologist Alexander Drilon, MD, research director of early drug development at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Rondell P. Graham, MBBS, head of GI/liver pathology at Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Dr. Drilon reported that the patient was 31 years old when she presented with progressive swelling in the left supraclavicular fossa. “Pertinent as part of her history, she had a previous diagnosis of stage IIIA Hodgkin lymphoma that was treated 16 years before she presented to us,” he said. When the medical records were scanned, they saw that she had been treated then with an ABVD regimen of chemotherapy and radiation to the abdomen and left supraclavicular fossa. Her past medical history was remarkable for hyperlipidemia and hypothyroidism. She had no prior surgeries. The physical exam “was notable only for a two-centimeter lymph node in the left supraclavicular fossa,” he said.

As part of their workup, the patient received a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a PET scan, which demonstrated hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy in the bilateral supraclavicular regions, lower cervical chains, and mediastinum. “Her laboratory examinations were unremarkable, so a pretty bland workup except for a mild elevation of CA 19-9,” Dr. Drilon said. A local surgeon performed a left neck dissection.

As part of their workup, the patient received a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a PET scan, which demonstrated hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy in the bilateral supraclavicular regions, lower cervical chains, and mediastinum. “Her laboratory examinations were unremarkable, so a pretty bland workup except for a mild elevation of CA 19-9,” Dr. Drilon said. A local surgeon performed a left neck dissection.

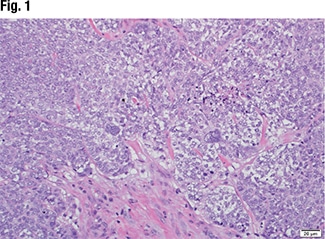

Dr. Graham displayed the image of a tissue specimen from a similar case (Fig. 1). “We have a neoplasm characterized by moderate-sized neoplastic cells with focal chromatin, prominent macronucleoli. And there are some occasional cells that show severe nuclear pleomorphism and multi-nucleation.” He also pointed out a brisk mitotic rate and some foci of necrosis. “A tumor that has a nonspecific look, such as this, is something we encounter rather frequently in our practice.”

The immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin 7 and negative for keratin 20, TTF-1, CDX2, thyroglobulin, vimentin, ER, PR, mammaglobin, GATA3, and PAX8. “So it was finally classified as a metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma of unknown primary.”

Dr. Graham noted that 60 percent of carcinomas of unknown primary are adenocarcinomas. Thirty percent are poorly differentiated carcinomas (of an unknown type), and then there are small percentages of squamous cell carcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma, he said. There are therefore two broad categories of CUP: a common carcinoma type that pathologists can recognize (e.g. adenocarcinoma) and a high-grade/poorly differentiated carcinoma type they cannot specifically identify. “And even at this level, this dichotomy is useful to be able to include in your reports.”

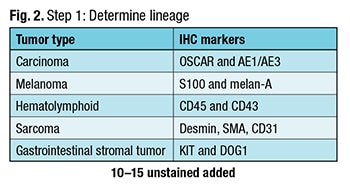

Dr. Graham described what he calls a “safe stepwise approach” to carcinoma of unknown primary workup. The first step: Determine the lineage. “It is a step that if one isn’t judicious, there is the potential for patient harm,” he cautions. As an example, “If the patient truly has a diagnosis of lymphoma, and it was instead signed out as a poorly differentiated carcinoma, there is the potential for patient harm because you may have an inappropriate treatment option offered to the patient,” he said in a CAP TODAY interview. In step one (Fig. 2), Dr. Graham attempts to determine if the cancer is a carcinoma and uses two epithelial markers: OSCAR and AE1/AE3. He uses melan-A and S100 to test for melanoma, noting there are other markers. To detect a hematolymphoid cancer, he uses CD45 with CD43. Some lymphomas don’t express CD45, Dr. Graham explained, so he likes to use the combination. To screen for sarcomas, he chooses desmin, SMA, and CD31.

In step one (Fig. 2), Dr. Graham attempts to determine if the cancer is a carcinoma and uses two epithelial markers: OSCAR and AE1/AE3. He uses melan-A and S100 to test for melanoma, noting there are other markers. To detect a hematolymphoid cancer, he uses CD45 with CD43. Some lymphomas don’t express CD45, Dr. Graham explained, so he likes to use the combination. To screen for sarcomas, he chooses desmin, SMA, and CD31.

Dr. Graham also includes KIT and DOG1 for gastrointestinal stromal tumor in the initial panel because he has seen GIST overlooked on numerous occasions. “It is occasionally forgotten, and this is a diagnosis you can make and for which the patient can be treated.”

Narrowing the differential is step two (Fig. 3). Once Dr. Graham has completed the first step and suspects the cancer is a carcinoma, he finds keratin 7 and keratin 20 to be helpful. The markers are available in many practices, “and they narrow the differential diagnosis for carcinomas,” he said, “because there are some patterns where the differential diagnosis is really quite short.”

Dr. Graham uses synaptophysin and chromogranin to distinguish neuroendocrine neoplasms. If those markers are positive, he includes Ki-67. “The main value of Ki-67 is determining the tumor grade, which has prognostic value. It also informs the oncologist on its potential responsiveness to platinum-based chemotherapy in the context of neuroendocrine carcinoma,” he said.

“I do p40,” he added, “because if it is positive, I can look for whether it expresses high-risk HPV or not, because that narrows the differential diagnosis and may have therapeutic implications.”

If keratins 7 and 20 are negative, the pathologist has to contemplate a short list of four carcinomas: hepatocellular, prostate, renal cell, and adrenocortical. “If you see this profile, you have to rule out these differential diagnoses,” he said. A keratin 20 positive and keratin 7 negative also has a short differential: GI, urothelial cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. “By contrast, keratin 7 only positive carcinoma has a long differential. It can be difficult to remember all of the differential diagnoses at the top of your head, but once one has the keratin 7-20 profile in this context, the rest of the algorithm should efficiently lead to an answer.”

If keratins 7 and 20 are negative, the pathologist has to contemplate a short list of four carcinomas: hepatocellular, prostate, renal cell, and adrenocortical. “If you see this profile, you have to rule out these differential diagnoses,” he said. A keratin 20 positive and keratin 7 negative also has a short differential: GI, urothelial cell carcinoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma. “By contrast, keratin 7 only positive carcinoma has a long differential. It can be difficult to remember all of the differential diagnoses at the top of your head, but once one has the keratin 7-20 profile in this context, the rest of the algorithm should efficiently lead to an answer.”

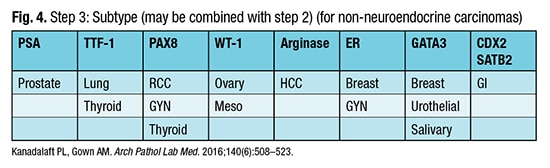

Step three is the refined search for the carcinoma subtype (Fig. 4) and may be concurrent with step two. “I do look at clinical information to see how to narrow and tailor this, if that is available to me,” Dr. Graham said. But his point is that “with a very limited pattern of markers, you can get to most diagnoses.”

Dr. Graham pointed out the caveats for step three. “For example, GATA3 can be positive in a lot of different tumor types. The initial papers touted its sensitivity for breast cancer and for urothelial carcinoma, but many different tumor types can be positive for GATA3.” TTF-1 is positive in neuroendocrine carcinomas, not only in the lung. “If someone has a small cell carcinoma, which is a histologic type of neuroendocrine carcinoma, regardless of the site of origin, TTF-1 can be positive.” One example is a small cell carcinoma from the urinary bladder.

A review of 12 studies found that the five most common occult primaries identified at autopsy are lung cancer, pancreatobiliary malignancy, other GI tumors, breast cancer, and ovarian carcinoma, Dr. Graham reported. “You want to make sure that when you finish your workup and you are ready to sign it out as a cancer of unknown primary, that you considered or excluded these possibilities as much as possible” (Massard C, et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8[12]:701–710).

The primary malignancies “you don’t want to miss,” he said, “because they have favorable prognoses and good treatment options,” are as follows:

- Breast cancer. If a patient has axillary lymphadenopathy, it is reasonable to be worried about breast cancer, he said.

- Prostate cancer. Blastic bone metastases and an elevated serum PSA would be suggestive of prostate cancer. “There is a newer prostate marker, NKX3.1, which is excellent if you have it in your lab,” he said.

- Colorectal cancer. Colorectal endoscopic findings may be helpful for their negative predictive value.

- Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cervical lymph nodes that are positive for carcinoma and for high-risk HPV strongly suggest oropharyngeal and base of tongue primaries, he said.

- Extragonadal germ cell tumor. “If you have mediastinal or retroperitoneal nodules or a mass in a young man, this is an important diagnosis to consider,” Dr. Graham said. In young adults, particularly men, he advises making sure that the prospect of a germ cell tumor has been ruled out.

Four IHC pitfalls are common sources of problems. No. 1 is skipping the first step; the pathologist does not determine the line of differentiation. No. 2 is lack of awareness of the “traps” in step three. For example, “urothelial primaries can show intestinal differentiation,” he explained, “and mucinous lung carcinoma can mimic a GI primary by immunohistochemistry.” The other two pitfalls: a failure to check the IHC controls and mislabeled slides.

To avoid exhausting the block before making a diagnosis, he offers these tips: split cores into separate blocks, face block for H&E and unstained at the same time, review H&E with clinical data before ordering IHC, and consider getting opinions before ordering.

Returning to the tumor board case, Dr. Drilon said their previous workup didn’t strongly suggest the tumor’s lineage. So the patient’s local physicians treated her with platinum-based doublet therapy. “It wasn’t clear why this particular regimen was chosen, although as per the local oncologist, the initial thought was this might have been a lung primary that manifested mostly as having metastases, with the occult lung primary not being found obviously on imaging. But thankfully, the patient had at least half a year of disease control, stable disease with this chemotherapy,” before there was progression in bone.

“Again, given that the local oncologist thought this might be more of a lung primary,” he continued, “pemetrexed was subsequently administered with five months of benefit, minor disease shrinkage. Unfortunately, that was again followed by worsening, widespread lymphadenopathy, and new metastases that involved the bone and new bilateral pulmonary nodules.”

“Again, given that the local oncologist thought this might be more of a lung primary,” he continued, “pemetrexed was subsequently administered with five months of benefit, minor disease shrinkage. Unfortunately, that was again followed by worsening, widespread lymphadenopathy, and new metastases that involved the bone and new bilateral pulmonary nodules.”

To help further characterize the case, the patient’s initial tumor biopsy was sent for next-generation sequencing. “By this time, the patient had seen us at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center where we have an internal next-generation sequencing assay, MSK-IMPACT,” Dr. Drilon said, describing it as a broad hybrid-capture–based—not amplicon-based—NGS platform that interrogates more than 460 different genes for copy number changes, recurring gene fusions, single nucleotide variants, and hotspot substitutions.

Using the panel, they discovered an IRF2BP2-NTRK1 fusion. “This was definitely in-frame and looked like it was an activating event because it included the kinase domain,” Dr. Drilon said. No other colonical tumor drivers were found in the sample. A splice site TP53 X25_ mutation was the only other alteration detected. “Our assay comes with an assessment of mutation burden and microsatellite stability or instability. And this tumor was deemed to be microsatellite stable with a low tumor mutation burden, which we do tend to see with these cancers that are driven by a colonical driver.”

Dr. Graham spoke about the role of molecular profiling in CUP from the laboratory’s viewpoint, and in doing so he was “wearing two hats,” he said, as a GI anatomic pathologist and a molecular pathologist. “When I talk about molecular profiling in CUP in my AP role, most colleagues are thinking about commercially available molecular assays to assign a site of origin. These are assays that are based on gene expression profiling looking at miRNAs or mRNAs to assign a site of origin.”

Dr. Drilon

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management