Karen Titus

July 2014—G-G-G-E♭. Also known as da-da-da-DUM.

Also known as the opening to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

It’s a simple motif, heard repeatedly in the piece (not to mention across the centuries), yet no less thrilling for that fact.

Maria M. Picken, MD, PhD, finds herself repeating an equally straightforward motif when she speaks about amyloidosis, and it, too, is worth hearing again: The disease is not being diagnosed early enough, and sometimes not at all. That theme has been a steady refrain of hers over the years, and it runs throughout a recent interview with CAP TODAY, so much so that she worries readers will respond with, Oh no, here she goes again.

But she’s willing to risk being tuned out. “This is so critical,” she says.

The stakes have always been high for patients with the disease. Now they’re even higher, given the advent of new treatments and the known long-term survival of patients who’ve been treated (read: diagnosed) early.

“A lot has changed in the last 10 years, especially with regard to treatment. But the problem of early diagnosis remains,” says Dr. Picken, professor of pathology, internal medicine (nephrology), and urology, and director of surgical pathology, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. It came to the fore again at the most recent meeting, this spring, of the International Society of Amyloidosis. “It was shown, again and again, that there is a high level of mortality at the beginning of treatment in a subset of patients—and these are the patients who are diagnosed late.” On the other hand, patients who are treated early and who respond to treatment tend to have durable responses, says Dr. Picken, noting that there is a cohort of patients who are alive 10 years post-treatment with bone marrow stem cell transplantation.

And so Dr. Picken persists. At the USCAP meeting in March, she spoke with CAP president Gene Herbek, MD—“very preliminary conversations,” she calls them—about how the College might establish recommendations and criteria for early detection and diagnosis of amyloidosis. She’s cowritten/coedited a textbook, Amyloid and Related Disorders: Surgical Pathology and Clinical Correlations (Humana Press/Springer). In her own practice as a renal/surgical pathologist, she frequently consults on amyloidosis cases. She also testifies in legal cases related to amyloidosis.

Pathologists, she says, need to claim ownership of the disease. “Nothing can happen unless it’s diagnosed in tissue.”

That requires them to look for it, a step that is still too rarely taken, she says. Even at the recent ISA meeting, the lack of pathologist presence was quite evident. “Only a handful of pathologists are active within this society,” says Dr. Picken. “The need to educate a broader pathology audience is very apparent.”

The first diagnostic step should be familiar to most pathologists, even if they rarely take it: perform a Congo red stain.

Before that can happen, however, physicians need to think about amyloidosis and order the test. Like planning for a summit meeting, the preliminary steps are as critical as the event itself.

While oncologists in particular are getting better at ordering the test—“They see the patient, and they obviously want to treat the patient,” says Dr. Picken—it still often falls to pathologists to be the first to think about amyloid and order the Congo red stain. “There is still not enough awareness among clinicians,” she says.

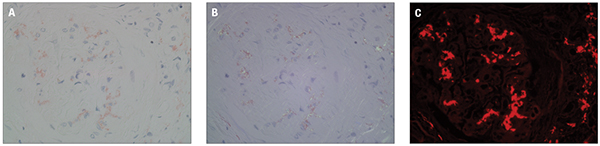

Three photographs (A–C) demonstrate a Congo red-stained paraffin section with kidney glomerulus. A shows the slide viewed in normal light (bright light), B shows the same field viewed under polarized light, and C shows the same field viewed under fluorescence light, using a TRITC filter. While only deposits detected under polarized light are truly diagnostic of amyloid, examination of Congo red-stained slides under fluorescence dramatically increases sensitivity.

In other cases, pathologists may decide a second opinion is in order, even after initial results are negative. Dr. Picken, who says she’s seen far too many missed diagnoses, calls this “a very good policy. Delayed diagnosis is terrible, and wrong diagnosis is very detrimental,” especially given the significant side effects of most treatments. “We’re not just talking about taking aspirin on a daily basis,” she says.

Treatments have advanced substantially for patients with the most common type of amyloidosis, AL amyloidosis, also known as primary amyloidosis, which is associated with plasma cell dyscrasia. Treatments are individualized and can include risk-adapted strategies (such as stem cell transplant) and combination therapies as well as heart transplantation.

There have been changes in managing hereditary amyloidosis as well, the most common type of which is derived from the transthyretin, or TTR, protein. TTR-related amyloidosis, or ATTR, is associated with a mutation in the transthyretin gene. Since the mid-’90s, when it was introduced, liver transplantation was the only treatment option. Now, however, there are pharmacologic options as well, with several clinical trials available for patients. Others are looking at the possibility of treating carriers of the defective gene prophylactically. “So again, a lot has changed.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management