May 2016—CAP TODAY and the Association for Molecular Pathology have teamed up to bring molecular case reports to CAP TODAY readers. AMP members write the reports using clinical cases from their own practices that show molecular testing’s important role in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Case report No. 11, which begins here, comes from Cooper Medical School at Rowan University and Cooper University Hospital, Camden, NJ. If you would like to submit a case report, please send email to the AMP at amp@amp.org. For more information about the AMP and all previously published case reports, visit www.amp.org.

Erica Schramm

William Kocher, MD

Tina Bocker Edmonston, MD

Case presentation. A 75-year-old man presented in the emergency department with the complaint of right shoulder pain for the prior three weeks, which was subsequently found to be due to a displaced clavicular fracture with no apparent history of trauma. His past medical history was significant for hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, aortic stenosis, and a high-grade superficially muscle-invasive carcinoma of the prostatic urethra diagnosed at an outside hospital two years prior. The cancer had been treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and radiation with complete response. In the emergency department, the patient was noted to be hypoxemic, and laboratory studies were significant for hypercalcemia, mildly elevated creatinine, abnormal liver function studies, and mild anemia. The patient was admitted for further evaluation.

Additional laboratory testing suggested a paraneoplastic etiology for the patient’s hypercalcemia. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses were normal. An ultrasound suggested a liver mass; however, this finding could not be confirmed definitively by CT scan. Subsequent imaging studies demonstrated radiolucent lesions involving ribs and thoracic spine, raising concern for metastatic disease. The main differential diagnoses for lytic bone metastases included squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, renal cell carcinoma, and breast cancer. However, imaging did not reveal any possible primary tumor. The patient became increasingly unstable with multiorgan failure such that biopsies of any of the bone lesions could not be obtained. Despite maximal medical intervention, he died two weeks after admission.

laboratory testing suggested a paraneoplastic etiology for the patient’s hypercalcemia. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses were normal. An ultrasound suggested a liver mass; however, this finding could not be confirmed definitively by CT scan. Subsequent imaging studies demonstrated radiolucent lesions involving ribs and thoracic spine, raising concern for metastatic disease. The main differential diagnoses for lytic bone metastases included squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, renal cell carcinoma, and breast cancer. However, imaging did not reveal any possible primary tumor. The patient became increasingly unstable with multiorgan failure such that biopsies of any of the bone lesions could not be obtained. Despite maximal medical intervention, he died two weeks after admission.

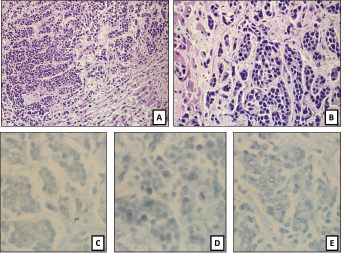

Autopsy revealed the presence of widespread metastatic disease in liver, spleen, perihepatic and common bile duct lymph nodes, right clavicle, and thoracic vertebrae. There was no evidence of malignancy in the prostate or urinary bladder. Histology showed metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma with neuroendocrine features; however, immunohistochemical stains for neuroendocrine markers S-100, chromogranin, and synaptophysin were all negative (Fig. 1). Despite evaluation of the histomorphology, the immunohistochemical profile, and the distribution of the metastases, the primary cancer of origin remained unknown. Histologic sections of the urothelial carcinoma that had been diagnosed at an outside institution two years prior were not available for review; however, the original histology had been described as grade three without mention of neuroendocrine features. The histology of the tumor found at autopsy did not provide any clues as to the origin. A paraffin block of the tumor was sent to a commercial laboratory (Rosetta Genomics) for its Cancer Origin Test.

Fig. 1. (A), (B): H&E of sections of a liver nodule show pleomorphic small blue round tumor cells growing in nests and trabeculi, suggesting a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma. Mitoses are present. Tumor cells are completely negative for (C) S-100, (D) synaptophysin, and (E) chromogranin.

The test uses microRNA expression microarrays for the quantitation of 64 microRNAs.1 Two classifiers are applied to determine the tissue of origin of the unknown primary. These classifiers were developed using microRNA profiles of a training set of 1,282 known and well-characterized tumors. A binary decision tree chooses the left or right branch based on the expression level and preset thresholds of one to three microRNAs at each node (Fig. 2). A second classifier, the K-nearest-neighbor (KNN), compares the expression across all 64 microRNAs to the data set of the 1,282 training samples and selects the majority diagnosis among the nearest five samples (Fig. 3). The binary decision tree and the KNN independently predict one of 42 tumor types, and in 82 percent of cases they agree on the tumor origin.1 For these cases, the accuracy of the molecular classification is 90 percent.1 In cases of disagreement between the binary decision tree and KNN, two possible cancers of origin are reported and ranked according to the calculated confidence measure of the two classifiers. In the reported case, the decision tree and KNN did agree and identified the metastases to be of urothelial origin. Additional immunohistochemical stains for uroplakin and GATA3 were subsequently performed and were positive, confirming the molecular result (Fig. 4). Cause of death was therefore determined to be widespread metastatic urothelial cell carcinoma.

Fig. 2. Binary decision tree from Rosetta Cancer Origin Test (courtesy of Rosetta Genomics). Each numbered square is a “node” with one to three defined microRNAs and preset thresholds of expression levels that determine whether the next step chooses the left or right branch. After passing through multiple nodes, the tumor reaches the final end of a branch that suggests a tumor type. A red line depicts the path of this tumor through the binary decision tree that ends with the tumor type “Urothelial Carcinoma (TCC).”

Discussion. Cancer of unknown primary, or CUP, often serves as a catchall diagnosis for metastatic cancer when a primary site has not been identified despite an extensive clinical and pathology workup, as in our case. It has been estimated that CUP makes up three to five percent of all new cancer diagnoses each year in the United States2 (about 50,000 to 70,000 new cases per year). The prognosis for patients with CUP is poor. Median survival from diagnosis is generally only three to four months, with one-year survival of 25 percent and five-year survival of 10 percent.3 About 60 percent of cancers of unknown primary are well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, 30 percent are poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or poorly differentiated carcinoma, five percent are squamous cell carcinomas, and five percent are poorly differentiated or undifferentiated malignant neoplasms.4CUP presents a challenging diagnostic dilemma for pathologists. By definition, extensive testing often does not reveal a clear tissue of origin. Even postmortem examination fails to identify the primary site in 15 to 25 percent of patients.5 For each individual patient, an exhaustive workup may ultimately include CT, MRI, PET scan, endoscopies, serum tumor markers, gross tumor morphology, pattern of spread, light microscopy, and immunohistochemistry.2 However, in about 30 percent of cases of cancer of unknown primary, the staining pattern does not give a final diagnosis.6 Patients whose primary cancer cannot be identified are often treated with empiric systemic platinum-based therapy, rather than chemotherapy specifically directed toward the underlying cancer. Studies suggest that only 25 to 35 percent of CUP respond to empiric therapy, increasing the median survival to nine months.7

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management