Valerie Neff Newitt

November 2022—Burnout among Canadian pathologists is prevalent, pain related for some, and workload driven for many. “There needs to be more of us,” says Julia Keith, MD, associate professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto and neuropathologist and director of wellness, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Molecular Diagnostics, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center, Toronto.

Dr. Keith is the author of a study published online Aug. 8 in the Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, titled “The Burnout in Canadian Pathology Initiative” (doi:10.5858/arpa.2021-0200-OA). Four hundred twenty-seven pathologists completed a survey across all 10 Canadian provinces, for a response rate of 50 percent of all Canadian Association of Pathologists members and 27 percent of all pathologists practicing within Canada. Most respondents (363) had completed the survey pre-pandemic, by March 2020. Sixty-four responded mid-COVID-19, in October 2020. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of burnout between the pre- and mid-pandemic cohorts.

Burnout was defined using the Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS) and characterized by three domains: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (feeling cynical or having a callous approach toward others), and a low sense of personal accomplishment (feeling ineffective in one’s work).

“The headline is the prevalence,” Dr. Keith says of the survey’s findings. “Fifty-eight percent of Canadian pathologists are burned out. And we know that physician burnout has negative implications for physicians themselves and for the quality of care they provide. So that’s a big deal.”

“Physician well-being, and pathologist well-being in particular, is a topic that warrants a great deal more scholarship,” she says.

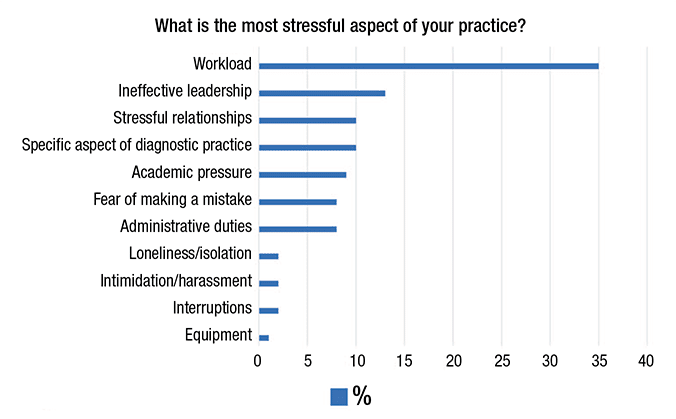

In the study, workload was found to be the top source of job-related stress, followed by ineffective leadership and stressful relationships (Fig. 1). It’s no surprise that workload came out on top, Dr. Keith says. “Workload is widely known as the major driver of physician burnout. So what can be done about it?” In response to an open-ended question about what pathology departments are doing to mitigate burnout, “some respondents described the process of workload assessment and subsequent attempts to distribute cases consistently and equitably as effective burnout mitigation strategies,” Dr. Keith says. “But the vast majority of workload-related departmental initiatives [reported by respondents to be effective] involved successful advocacy for more pathologist positions, more locum tenens. So I suspect our community needs to grow.”

Many workforce-related decisions are driven “by metrics, by evidence,” she adds. “So I’m hopeful that data from studies like this that demonstrate pathologist burnout prevalence can be useful to those who are advocating at various levels for more pathologist positions.”

A logical next step, in her view, could be to investigate the link between pathologist burnout and the quality of care pathologists provide. “Given the rigorous way that quality metrics are documented in laboratory medicine, our field is well positioned to study the relationship between physician burnout and medical error—patient safety—better than what has been done previously.”

Fig. 1. Top sources of job stress for Canadian pathologists shown as percentage of total responses mapping to each of 11 identified themes. From Keith J. Arch Pathol Lab Med. Published online Aug. 8, 2022. doi:10.5858/arpa.2021-0200-OA.

Another way to confront the physician burnout problem: build a business case for addressing burnout because of the associated physician turnover, reduced work effort, and early retirement. “These phenomena are financially costly,” Dr. Keith says.

An important finding of the study, she says, is the “relatively untapped opportunity for improvement” in practice flexibility. “The greater the amount of flexibility a given pathologist felt their department allows significantly correlated with lower scores on all domains of burnout.” Digital pathology and other such innovations in the field, she says, “have the capacity to allow for much more flexibility in when and where and how we do our work, and I am looking forward to seeing whether they have an impact in reducing pathologist burnout.” For pathology leaders, she adds, “I would encourage them to try to creatively foster flexibility in their own departments.”

Dr. Julia Keith: “The greater the amount of flexibility a given pathologist felt their department allows significantly correlated with lower scores on all domains of burnout.” [Photo by: Kevin Van Paassen/Sunnybrook]

At the departmental level, a wellness infrastructure was also reported to be helpful. The “easiest” wellness infrastructure strategies that were shared focus on communications, Dr. Keith says—for example, compiling wellness-related resources on a website or in a newsletter, having wellness as a standing agenda item at meetings to keep teams informed, and well-being themed educational opportunities or rounds. Other departmental wellness initiatives that respondents reported as being effective at reducing burnout, such as mindfulness training and formal institutional peer support programs, “are evidence-based interventions, meaning they have been shown to work.”

“The fundamental building block for wellness infrastructure is to appoint somebody as your physician or pathologist wellness lead, and then protect some of their time so they can do the job well,” she says. They need time to pursue training in physician well-being, such as the Stanford Physician Well-Being Director Course, to conduct needs assessments, and to implement wellness initiatives that are informed by local need, Dr. Keith says. “And involve your wellness lead in your leadership team.” There are sources of guidance not just for individuals, she says, but also for institutions that want to address burnout at a system level. They include, for example, programs of the National Academy of Medicine and the AMA. Hospitals that choose to participate in the AMA program, titled Joy in Medicine Health System Recognition Program, are awarded various levels of recognition based on their level of commitment to reducing burnout. “One of the takeaways for me when I read about these programs,” Dr. Keith says, “is how important it is for organizations to be able to demonstrate that they’re making operational decisions that take physician well-being into consideration, because in the absence of that, one runs the risk of whatever wellness infrastructure has been built as being viewed as a token gesture.”

At an individual level, “the answers respondents gave about effective individual burnout mitigation strategies overwhelmingly mapped to the burnout driver dimension of work-life integration,” Dr. Keith says, noting she thinks of work-life integration as “the things you do to take good care of yourself. The work-life integration strategies shared were highly variable, quite individual and personal, and there is no silver bullet.” The message for each pathologist, she says, is to “reflect on what aspect of self-care is currently working for us to some extent and to do our best to create space and energy for those things in order to foster our individual resilience.”

Fig. 2. Anatomic distribution of chronic work-related pain experienced by Canadian pathologists. Two hundred pathologists responded “yes” to experiencing any chronic work-related pain, many of whom selected multiple anatomic sites; 480 different “yes” responses were received across all anatomic areas. The total number of “yes” responses and the percentages shown for each anatomic site calculated out of a total of 480 responses are shown. From Keith J. Arch Pathol Lab Med. Published online Aug. 8, 2022. doi:10.5858/arpa.2021-0200-OA.

The two most commonly shared individual burnout mitigation strategies were exercise and having rules around one’s own work hours. “Some people say they curfew their day. They leave the office at a given point in time, even if some work is unfinished,” Dr. Keith says. “Some have rules that they never go into the office on weekends; others say working a few hours on the weekends sets them up for a better week.”

“But I want to emphasize that lack of individual pathologist resilience is not the root of the burnout problem.”

For Dr. Keith, the biggest surprise in the study results is the prevalence of chronic pain among respondents, with 47 percent reporting work-related chronic pain (61 percent of female pathologists, 32 percent of male pathologists) (Fig. 2). “And the presence of chronic pain significantly correlated with pathologist burnout, so I suspect that work-related pain may be a specialty-specific driver of pathologist burnout. And I think it may be the lowest-hanging fruit.”

One of her own work-life integration strategies is pain related. A few years ago she developed chronic low back pain, likely from years of sitting all day at the microscope and computer, so she reconfigured her office. The computer is now on a standing desk; the microscope requires her to sit on a stool. “And I physically separated those two workstations. As I make my way through my stack of cases I’m frequently changing between a seated and a standing position. I essentially found a way to incorporate some movement into my workflow.” When she began to speak about her office reconfiguration, other Canadian pathologists shared with her the changes they made. “This is an important lesson for junior pathologists and for trainees to hear: Perhaps they shouldn’t be configuring their offices in a conventional way. I suspect that the traditional setup of a pathologist’s office is not working well for many of us.”

Ergonomic assessments of workspaces can be helpful if the expertise is available, she says, but they are most helpful preventively and, in her view, not the full solution. “In my opinion, the pathologist pain problem is bigger than what we can solve just by using ergonomic microscopes and having a perfectly designed office chair that we proceed to sit in all day. I suspect that the extremely sedentary nature of our work is part of the pain problem. So creating ways to incorporate movement into our workday may also help.”

Not surprising to Dr. Keith were the findings that female pathologists reported higher levels of emotional exhaustion and lower levels of personal accomplishment than male pathologists (P=.001, P=.03, respectively). “I was aware of there being a gender gap in physician burnout. There’s a gender gap in remuneration in medicine as well, and, in my opinion, there remains a subtle but persistent amount of gender bias.” Her study’s findings were pre-COVID, she notes. “One of the ways COVID has impacted physicians is that the gender gap in burnout has widened.”

Thirty percent of respondents had been in practice five or fewer years, 17 percent for between six and 10 years, 25 percent for 11 to 20 years, and 28 percent for 20 or more years. Sixty-eight percent were practicing in an academic setting, 23 percent in a community hospital with an academic affiliation, 7.3 percent in a community hospital without an academic affiliation, and 1.2 percent in a private laboratory. Seventy percent of respondents were anatomic pathologists. The differences in the way pathology is practiced in Canada compared with that in other countries, including the United States, could have an impact on its generalizability, Dr. Keith notes in the study. Whether these differences “result in subtle or drastic differences in the pathologist burnout prevalence and drivers requires further study,” she writes.

She cites in her paper several previous studies of physicians that reported lower levels of burnout among pathologists, and says possible explanations are the better response rate in this study and that it relied on the widely used Maslach Burnout Inventory-HSS psychological tool for measuring burnout in health care workers. She writes, “The possibility that burnout may be much more prevalent within our specialty than previously reported is alarming from an ethical and moral perspective, as our community may be more vulnerable to or suffering from the adverse personal and relational consequences of burnout than previously realized. . . . It is also alarming from a patient safety perspective.”

But she is not nihilistic about the problem of pathologist burnout, she tells CAP TODAY. “Rather, I’m hopeful. I believe there is a lot that can be done.”

Valerie Neff Newitt is a writer in Audubon, Pa.