September 2020—Between a rock and a hard place. Trying to stay ahead, trying to build inventory. Chasing multiple new testing requests. Anticipating influenza.

That’s where laboratory leaders said their labs were in early August when CAP TODAY publisher Bob McGonnagle convened members of the Compass Group on Zoom to share their pandemic experiences. They shared surprise, too, that the situation is what it is: “Not a clue in my mind that this would go past the springtime,” said Stan Schofield, president of NorDx and senior VP, MaineHealth.

McGonnagle asked them about the diversion of supplies, the coming flu season, IT support, lessons and long-term changes, and more, including: “Why doesn’t pathology and laboratory medicine have a Dr. Fauci?”

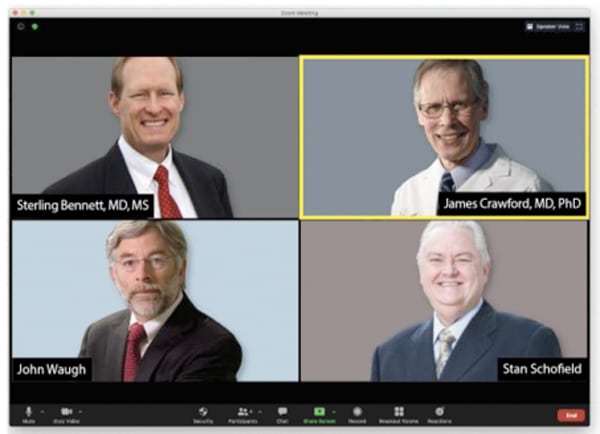

On the call, in addition to Schofield, were Gregory Sossaman, MD, of Ochsner; Judy Lyzak, MD, MBA, of Alverno; Sterling Bennett, MD, MS, of Intermountain; James Crawford, MD, PhD, Mike Eller, and Dwayne Breining, MD, of Northwell; John Waugh of Henry Ford; Robert Carlson, MD, of NorDx; Pamela Murphy, APRN, PhD, of Medical University of South Carolina Health; Susan Fuhrman, MD, of OhioHealth; and Norman Gayle of Regional Medical Laboratory.

The Compass Group is an organization of not-for-profit IDN system lab leaders who collaborate to identify and share best practices and strategies. Here is what they told us.

Did you have any idea when you first began to understand the severity of the pandemic that we would still be in the same place on Aug. 4? One of the Compass Group members, Susan Fuhrman of OhioHealth, said, and I quote from a CAP TODAY story published in August, “It just keeps getting surprisingly worse.” Greg Sossaman, do you have a reaction to that? And would you in your wildest dreams have thought you would be up in the air on Aug. 4?

Gregory Sossaman, MD, system chairman and service line leader, pathology and laboratory medicine, Ochsner Health: I agree with Susan Fuhrman in her assessment. We continue to bring up and expand testing, but it just continues to be more complicated.

Schools are beginning to start here next week and that scares me. More literature is coming out about how children are not as protected as initially thought and that they can be very infectious, and yet nobody has a school testing program. We don’t have the capacity to test teachers and students every day like they should be tested.

We now have a decent handle on the patient testing we’re doing, but we struggle with community and employer testing. We are using every single test we have every day and continue to bring up more. I didn’t think it could get more complex, and I thought we would be back to a new abnormal by now.

Stan Schofield, did you have any idea we would still be in this boat on Aug. 4?

Stan Schofield, president, NorDx, and senior VP, MaineHealth: No. We had the assay ready to go in mid-February, a laboratory-developed test, and I had inventory and supplies for 6,000 patients. I thought I was wasting money. I thought this is overkill, like the swine flu of 10 years ago where you wind up eating a lot of reagents. We blew through that in three weeks and have been on a scavenger hunt since then—all day, every day—to get supplies and materials. Not a clue in my mind that this would go past the springtime. And as Greg Sossaman said, we have industry, corporations, universities. Everybody wants to get tested. And it’s hard to try to help the community in general because of the limitation in reagents, supplies, and equipment. We’re meeting the needs of the health care system—keeping it fairly COVID-free for elective surgeries and diagnostic procedures—but there’s not a lot left over after that to help the community in general.

Members of the Compass Group, among them Dr. Bennett, Dr. Crawford, John Waugh, and Stan Schofield, met by Zoom in August to talk about where things stood for clinical laboratories. “This has been a sobering lesson in the fragility of our system,” Dr. Crawford said, noting it’s about more than pandemics, and adding, “As laboratory leaders, we have to be much more mindful of that fragility.”

So we’re kind of between a rock and a hard place. We’re going into a big service demand time period and there’s very little we can do to offer support or help.

There’s a lot of finger-pointing going on, and a lot of people seem to think reagents can be stamped out as if they were widgets. In terms of the industry being caught short, they can talk about producing reagents and the time it takes to do so. It’s more like brewing a great beer than it is stamping out a bunch of metal parts. Stan, can you talk about that?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): You’re correct. We were all geared up for a world of great efficiency and low-cost operations. Not a lot of excess capacity. And the diagnostic companies were tooled up and managed to meet those needs in a strong business environment with a lot of competition. They couldn’t have a lot of waste or a lot of development cost. And SARS-CoV-2, in moving so quickly, caught everyone flat-footed and stupid. It was on us before we knew what was happening. The government was slow to react. Most of these diagnostic companies are big ships; you can’t turn them around in the middle of the bay. And with a bridge and everything else to worry about for regulations, standards, and quality, they’ve done a pretty good job. It’s been compounded because now it’s global and all these companies are global companies. So it’s not just what we want, it’s what the world wants.

We could have done a better job and a few more things, but the government has gotten involved a lot with this. The redirection, redeployment of supplies has not gone well, and a lot of areas have been stranded. The government’s position is more or less, save the cities, let the countryside burn. And while the countryside is burning now, there’s not much to redeploy because the demand is growing, not only from a political standpoint but also from a community and public standpoint. We get requests every day. They’re not sick; they need a test so they can go back to college or elsewhere.

The diagnostic companies—fixed, well-established organizations that can’t easily expand—have had unprecedented demand. You can’t build giant molecular diagnostic manufacturing factories in 30 or 40 days. Giving them the benefit of the doubt, from what I’m hearing, most are expanding and working hard to do that.

Dr. Lyzak

Judy Lyzak, what’s going on at Alverno? Are you largely in agreement with what you’ve heard from your colleagues so far?

Judy Lyzak, MD, MBA, VP of medical affairs, Alverno Laboratories, Indiana and Illinois: Yes, we’re very much in the same boat. We’re doing okay on our core-laboratory–performed tests, but we’re encountering a real shortage with the rapid molecular test in the hospital—our Abbott ID Now. Thankfully, we’ve controlled the utilization of that test with strict algorithms and guidelines on how our physicians can use it and for what patients, so the impact of the allocation limitations has been minimized. But it’s still a little startling when you are used to practicing until this point in a land of plenty. It was a little startling, as it is to learn daily from a vendor, that an allocation you assumed was going to be delivered at a certain point that very day has been likely redirected to someone else. And then you have to have the unpleasant conversations in real time with your clinicians across a vast geography to tell them that now they have to practice in a world of limited resources and without a rapid test for use in the ED.

If the Compass Group members are having trouble getting adequate supplies for their testing needs, what is happening at the 100-bed hospital in rural Utah or western Nebraska or South Dakota? Your labs should be as well taken care of as anyone in the country, and yet I know you’re not. And I know from LabCorp and Quest that even their public statements about turnaround times are highly optimistic. So what, from your perspective, Sterling Bennett, is explaining some of this?

Sterling Bennett, MD, MS, medical director, Intermountain Healthcare central laboratory, Salt Lake City: The situation in the rural areas is variable. We were contacted by our Cepheid rep, who said they have been instructed to provide x number of rapid molecular tests to three rural hospitals, and they had a designated list. They were receiving instructions from somewhere out in the ether that these rural facilities needed to be given preferential treatment with a quota of tests that vastly exceeded the usage in their communities. But then we have other facilities that seem to have no access at all to testing supplies. So it seems to be highly variable. And I think the main underlying reason is that none of us has ever lived through this before, and we’re all making it up as we go. People in industry are making it up in a different way than people in government, who are making it up in a different way than the people in health care.

One of the themes that has emerged almost from the start has been a dissatisfaction with a national policy. That’s a discontent that seems to be constant even though it has morphed. At the start there was a limited algorithm for people to get these tests, and now it seems like the sky’s the limit, that everybody almost as a right needs to have their molecular PCR status of COVID known. And that’s what’s in part gumming up the system, and the test shortage will continue well into the flu season. Would anyone like to speak in favor of returning to a national algorithm for patient testing?

Dr. Breining

Dwayne Breining, MD, executive director, Northwell Health Laboratories, New York: It would be nice if there were a coherent strategy tying up all the loose ends, because having everybody competing against everybody else is not optimizing the situation.

I’m of a mixed mind about the national testing algorithm, because in terms of reopening the economy in the New York area, you do want to be able to swab as many people as you can. Basically every citizen of the New York area is at risk for exposure because it was so prominent here. And to identify patients and then isolate, you want to be able to do the swabs. At the same time, we don’t have nearly the capacity we wish we had. I’ve been in conversations with the governmental offices about possible alternative testing strategies for ongoing surveillance of institutions like schools, colleges, those types of things, where we can possibly bring antibody testing into the algorithm to do an ongoing surveillance of seroprevalence rates. But of course that would need to be accompanied by swab testing, at least in the initial phases and in some sort of ongoing sampling algorithm. So it’s preliminary at this point.

As for that small country hospital in the Dakotas or Utah that you brought up, if it doesn’t have cartridge-based testing—and I don’t think anyone has enough of that at this point—it has to send to the national commercial labs. Quest has been overwhelmed—we have had tests that have gone to Quest that are 18 days and still pending results. LabCorp, I think, is faring a little bit better. That’s because they’re charging more for the testing, so they diverted some of the demand. All of the national labs are telling the same story, and they are overwhelmed.

James Crawford, MD, PhD, professor and chair, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and senior VP of laboratory services, Northwell Health, New York: Regarding your prior question, you don’t have to be in South or North Dakota. Upstate New York is experiencing the same problem—the community hospitals don’t have the capacity.

My concern is that the solution might be worse than the problem. There’s discussion, at least at the New York State consortium level, about how nice it would be to have pathologists involved in these planning decisions, but that doorway has not opened up. Instead, it’s our health system CEOs who have the governor’s ear. Dr. Breining has his own back door to the governor’s council. Other states’ laboratories may have better channels to the policymakers. But the idea of people who have nothing to do with the lab industry coordinating national lab test supply is something we should be careful about recommending. I’d love to see national coordination, but I am not alone in saying it depends on who is in the room.

John Waugh, you’ve been observing this lab world for a long time, always with great insight. Why does the laboratory seem to be so shut out from some of the decisions that need to be made?

John Waugh, system VP, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit: Some of this is politics and some of it is science, as all of us know now. Unfortunately, the politics are happening; we’re in the middle of a political season. And that emphasizes a lot of the trigger points. But there is no question that at the federal level there is a big impact on moving around supplies. And the question was raised about where it’s coming from. It’s the White House Coronavirus Task Force. It’s Admiral Brett Giroir. I was on a conference call with him two weeks ago, and on that call he said, “I’m taking NIH money from Dr. [Francis] Collins here, and I’m going to buy consumable supplies from Hologic. And I’m going to move that to where I need it.” And he did the same with products from Abbott and Roche. So there are big, heavy hands moving these around.

And then he said—and I’m not judging whether it’s good or bad—what they want is the testing numbers to go up. Everything that was presented got approved as an EUA, so we had a lot of bad product out there, and now they’re trying to reel that back in. But going forward, his position is that we have to have more testing, we have to have cheaper testing, everybody doesn’t need PCR testing with its costs and time constraints, and we need to get down to testing at maybe $2 to $5. I can’t imagine what those kinds of tests are going to be or what the utility will be. But here’s somebody who doesn’t make his living in diagnostics—probably a great admiral, a great pediatric intensivist—but as assistant secretary for health in the Department of Health and Human Services he wields a lot of authority on how to move product around.

I’ve talked with company executives, even to the CEO level, who are cautious in not wanting to lose control of their supply chain. And the federal government has a spreadsheet it is keeping with 14, 15 company names on it of what’s being produced and where it is going. And these company executives have to make sure they’re moving product to the hot spots and underserved areas. Otherwise they’re going to lose control of their supply chain. And they want to take care of their own customers without having the federal government do it for them.

Robert Carlson, is a national algorithm, or a new algorithm for selecting patients to be tested, a little like trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube? Is the genie out of the bottle and we just have to deal with it?

Dr. Carlson

Robert Carlson, MD, medical director, NorDx, MaineHealth: I’m afraid you’re right. I call it boiling the ocean. There are so many different demands. A logical, systematic approach where the sickest or the ones who need the test the most get the test would be a good start. But the demand is so far outstripping the supply that it’s going to be difficult to even begin to think about rationing, other than what the government is doing.

To what degree are the various health care systems back to business as usual? Elective surgeries, school physicals, et cetera. Greg Sossaman, what’s going on at Ochsner?

Dr. Sossaman (Ochsner): We’ve mostly resumed—surgery and clinic visits are back. Some of it has changed a bit, but most of that volume has come back. We’re probably in a little better position than some of the other hospitals in the state with such things as ICU capacity. Overall as a system, we are doing very well compared with where we were in March and April, though we’re not where we wanted to be at this point compared with last year.

Is this returning volume also crimping your ability to generate the kind of COVID tests that are demanded of you within the system?

Dr. Sossaman

Dr. Sossaman (Ochsner): There’s definitely competition for resources. For a while we were pulling staffing from other areas to work in our molecular lab at night or in other areas. Yes, as volume has come back, those techs have gone back to those areas, so it’s been difficult to maintain staffing in our molecular areas.

Stan Schofield, how is the return of some normalcy affecting your ability to operate the laboratories?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): Surgeries are about 90 percent back to pre-COVID norms for the big hospitals. For the small hospitals, it’s about 70 percent. The ambulatory setting is at about 80 to 85 percent based on locale in the state and population density. We are approaching our capacity under social distancing and physical and scheduling limitations.

We’ve added multiple lab staff to molecular. I’ve asked for more people to be recruited. For the next 12 to 18 months, we’ll never have enough people. But we’re going to keep trying to stay ahead of the curve because of the demand, because reagents are going to catch up and we’re going to be okay. But then we’re going to have the preanalytic bottleneck, the specimen collection. And we’ve been buying and expanding testing capacity with instrumentation and automation. So we’re trying to stay ahead by adding preanalytic and molecular people at every opportunity.

We’ve expanded a lot, but it’s not enough. What I see is the demand going into the fall with the flu and COVID combination.

The COVID asymptomatic demands are increasing every day—presurgery, pre-diagnostic, MRI, CT scan, labor and delivery. Now medical students have to be tested weekly, and all of this is rolling in. The number of asymptomatic patients exceeds the number of our symptomatic patients by 30 percent on an average day.

It takes a lot of resources to keep the health care system a COVID-free zone, so people don’t stay away. And the data are impressive: 20,000 people pre-screened, 25 are positive. That works, and it’s good information. But then everybody says, okay, that’s what I’ve got to have. I don’t want rapid ID Now; I want molecular. It’s the gold standard; I can count on it. And anything less than that is not acceptable to the medical staff.

Sterling Bennett, what are your thoughts on this? As the system returns to something a bit more normal, it’s clear that puts even greater demands on the laboratory.

Dr. Bennett (Intermountain): It does. So we’ve seen essentially a rebound to baseline for our laboratory volumes and our anatomic pathology volumes. Not quite, but close. Initially, as others have described, we shuffled people to do COVID testing, and as the volumes rebounded we had to move them back out. So we’ve had to fish around the system and redeploy individuals from other areas to keep the COVID testing flowing.

Judy Lyzak, are all your surgical pathologists back at the scope?

Dr. Lyzak (Alverno): We are. Our volumes have rebounded to about 80 to 90 percent of where they were—some hospitals a little more than others. So, yes, we are clawing our way back. And we are experiencing many of the same problems that my colleagues on today’s call have spoken to. One of our limiting factors, in addition to the supply chain problems, is having enough staff to push these thousands of tests through every day and meet the physicians’ expectations on turnaround time. When we introduced the risk assessment for surgeries, they wanted those faster than anything, and then they complained we couldn’t get the risk assessments done as quickly as they wanted and take care of all the acute patients as well. So balancing all of that, and using the EMR technology to configure those orderables so we understand how to prioritize things in the laboratory, has been a real challenge.

We’re about to go into a flu season, and it would seem as though the demand is going to be exponentially raised to put this testing on some kind of a multiplex system that can do flu A and B plus COVID. Dwayne Breining, is that your assessment of what’s going to happen to us once the flu gets its first foothold on the system?

Dr. Breining (Northwell): That’s exactly right. If you look at especially the crowded urban hospital setting, in a normal flu season the hallways back up with patients waiting for flu results, even when we do have enough flu testing in the hospitals. You can imagine now the patient cohorting nightmare that’s going to occur because anyone coming in with flu-like symptoms is going to need to be tested for COVID and flu. We see a lot of RSV as well.

So our approach is to try to have the multiplex cartridge-based testing available for all the hospitals that need it for patient cohorting. But of course with what’s gone on with the cartridge-based testing systems, it’s the same factories making the cartridges. And then the manufacturers can load them up with whatever reagents they want. So a number of the vendors have said they’re opening up new factories and they assure us they’ll have enough supply.

The military and other organizations love these test systems because they’re so easy to use. They can grab them by the truckload and the shipload whenever they think they need it. I heard one person, possibly from West Point, in an unguarded moment in a radio interview talk about how they were testing all the cadets daily. I expect that kind of thing is going to continue well into the flu season. So we’re pretty worried about that, because the other thing the clinicians tell us is that in a normal flu season, they don’t test nine out of 10 people who come in with symptoms, because once the flu is prevalent, they pretty much know what they have. They’re thinking they’re probably going to have to test everybody this year. I doubt they’re that disciplined in normal practice, but I’m sure they’re not testing everybody, either. So there are going to be more orders.

But, fingers crossed, based on the information coming in from the Southern Hemisphere, they’re seeing almost no flu season at all so far. And all of the social distancing and masking should have some effect on the propagation of the flu virus. Maybe we’ll get lucky.

John Waugh, do you already have your feelers out for these multianalyte panels?

John Waugh (Henry Ford): We’re looking at the usual suspects that have test systems that are out there. The challenges are going to be in worldwide allocation. If it were only the United States, we’d be okay. But we’ve got the whole rest of the world. And we’ve got all of our hot spots where product gets shipped to prioritize for those areas. But as Dwayne Breining says, people are not going to be terribly troubled about the flu, but if they have respiratory symptoms, everybody is going to want to know if they have COVID. Because that’s the bad actor here. Products that have flu A/B, RSV, and COVID are going to be the ones people want.

Some of those run on large platforms. Some are more rapid tests. But even the ones that are more rapid tests may be 20-minute or 30-minute tests. Typically when we do seasonal influenza testing, we test patients while they’re still in the clinic or urgent care area. The question is, how long do you want to clog people up waiting in those areas, getting close to each other or coughing and sneezing, while you’re waiting for those test results? A lot of the COVID testing right now is not rapid point-of-care testing. It’s going back to the laboratory and being done on big platforms.

Pamela Murphy, how are you implementing the COVID antigen tests, if at all? And what does your supply chain look like at MUSC?

Dr. Murphy

Pamela Murphy, PhD, APRN, system administrator, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Integrated Clinical Center of Excellence, Medical University of South Carolina Health, Charleston: We are not using any of the antigen tests now. We are doing PCR testing on the Abbott m2000, and we have three of those. Two are old and failing frequently with their use now. We have one Alinity m that we got about two months ago, and we’re getting a second one in the next month or two. In the past few weeks we have run into pipette tip issues, just like almost everyone else. That put a hindrance on our capacity. We’ve now been able to get those back in, but it changes week to week. We are also using the Cepheid GeneXpert, but our allocation is limited.

So we are constantly looking at equipment issues, supply chain issues, people issues, not being able to recruit enough to run our testing. And referral labs are waxing and waning as well, as they have had capacity issues as well as people—COVID-positive—issues.

Did you have any idea in March that we would be in August facing the situation we are all facing today?

Dr. Murphy (MUSC): None at all. It’s been very challenging for our team. We are constantly being asked to pivot. Right now the politics play in quite a bit. And so we have been asked to now look at nasal swabbing or saliva testing. And there’s a lot of pressure on our teams to try to validate and make that work. But we are 100 percent NP swabs right now.

Norman Gayle, what is your perspective? Are you in consensus with what you’re hearing from your colleagues, or do you have new wrinkles you’d like to share?

Norman Gayle, VP and chief operating officer, Regional Medical Laboratory, Tulsa, Okla.: It’s interesting to hear that we are all experiencing similar challenges, and without a doubt everything that has been mentioned is common to us here in Oklahoma and the region we serve. No idea whatsoever that we would at this juncture still be in the height of this pandemic from a laboratory testing perspective. And as you all probably are aware, Oklahoma is bordering on the orange-red level now for the past seven days. We’ve crunched out greater than 10,000 tests over the past seven days, and the positive rate has ranged from about 9.2 percent to 14 percent. Our overall positive percentage since day one, which would be March 20, when we rolled out our first test, is now at about 6.2 percent.

The challenges with supplies abound. We have seen some improvements in this area through collaborative efforts with our national laboratory leaders and with the national suppliers. We have three platforms constituting six instruments dedicated to COVID testing: two Abbott m2000s, two DiaSorin MDXs, and two Hologic Panthers. And we just started to install the Abbott Alinity m platform.

Surgeries have returned for the most part to pre-COVID levels. We ran into major national supply shortages over the past two weeks, and it had our surgeons stepping back a bit to reassess the COVID-19 presurgical testing plan.

Epic is in the headlines today because the company has called all its people who have been working at home back to Verona, Wis., to start programming and building, and people are complaining. Stan Schofield, would you like to comment on IT support in the midst of a pandemic?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): IT support would be nice if it would ever start. We’re finding that IT projects are still slow; it’s hard to communicate when we’re not easily together. Lots of Zoom and GoToMeeting calls, and things are not happening in a rapid, timely fashion. Reporting requirements are difficult. Ask on order entry—we have 10 elements we have to do for the CDC—every one of these tests that comes in now. And the state of Maine has one setup. We do work in New Hampshire; that state wants a different format for its reports. And it’s problematic to get IT to do any of this kind of thing remotely. So the idea of Epic and people going back to work, or not working—this whole thing is a mess. Most of the time the Epic people do not have a lot of compassion for or understanding of the laboratory’s needs during this pandemic. (Editor’s note: Epic rescinded its requirement for employees to return to the company’s campus this year.)

What will be the lessons learned from COVID as we work our way through this, and what do you foresee as possible major structural changes in the laboratory world, in the laboratory industry, that may arise out of the pandemic?

Dr. Bennett (Intermountain): One of the immediate lessons learned is that we need to maintain inventory levels less lean than we have done in the past. It will be a long time before we go back to something that approximates just-in-time inventory. So we’re trying to build inventory of all lab supplies. I know there’s some expense to that. But also from a long-term perspective, I believe the IVD industry is going to be reexamining how it manages its supply chain as well, to avoid shortages or rolling shortages and to prepare for unanticipated events.

Another lesson we’ve learned is that relationships are really important. We need to make sure we have solid relationships with executives in our health system. We’ve found that the relationships even within the laboratory service have been critical. And in a perverse or an unexpected way, this COVID crisis has helped us organizationally within lab services because we huddle together frequently on issues like managing the inventory of the cartridge-based tests, the rapid tests, making sure people are all on the same page with the information they need. We know each other better, we work together better, and I think we’ll see long-term benefits from that.

We’ve also looked at external relationships with our state public health lab and with ARUP. We have helped each other fill shortages of supplies and reagents and had a cooperative effort that has emphasized the importance for us to be on good terms with people in our community.

Dr. Crawford (Northwell): And I would go in the same direction. Advice given to me long ago was to make your friends before you need them. What we’ve experienced in the past five months by way of community has, I hope, been transformational. We’ve all been friends and we’ve had contacts in various places, including in public health, but this episode makes abundantly clear the need to have strong relationships, personal relationships as best as possible with public health, with the state, and across our national laboratory community.

Something that we discovered in New York, and I understand it has occurred to a certain extent in other states, is an ad hoc consortia of laboratory communities to deal with these issues. For us it was the assembled laboratory leadership of 11 major New York State academic health systems. Although we didn’t specifically help each other meet our direct institutional needs, the advocacy of this consortium with the state was helpful just by way of communication. There are other examples in other states. I also think the relationship with manufacturers can only be strengthened.

This has been a sobering lesson in the fragility of our system. And it isn’t just about pandemics. When the tsunami hit Fukushima, the one plant—I believe it was Roche that made pipettes—was taken out. And it was a dicey time. As laboratory leaders, we have to be much more mindful of that fragility. And while it starts with stockpiling, I think it also includes contingency planning as we move forward. This has been quite a lesson in that regard as well.

Can you foresee any unpleasant long-term changes to the laboratory industry, whether they might be regulatory or having a testing czar of sorts, which I think would be, to say the least, a double-edged sword?

Dr. Crawford (Northwell): I’ll make two points. The first is regulatory. The relaxation of regulations raises the question of what we should reassemble as the agencies that relaxed the regulations say, “Let’s just go back to the way it was before.” I would argue for a cogent advocacy to examine the regulations that were relaxed and see if we can get a more streamlined regulatory landscape. I’m not saying there should be an absence of regulations, but just examine the pros and cons of what we’ve seen during relaxation. An example is remote sign-out by digital pathology—this has been a very effective option. But it was a rather wild time with the testing EUAs that were issued. Let’s learn from this sequence and be thoughtful as stricter regulations are reinstated.

But my second concern is the landscape over which the laboratory industry travels. On the one hand, the smaller the lab, the more vulnerable it is. The bigger the lab, potentially the more advantages. But I worry about near-patient testing, which is what the smaller labs provide. I think what has been trampled during the COVID-19 sequence is the importance of the labs proximate to patient care and the communities they serve.

I appreciated governor Andrew Cuomo’s recent editorial saying it isn’t just about the big-box labs. He makes specific mention of the 260 non-commercial labs in New York State that are helping to meet the state testing capacity. I’d love to have that broader diversity of laboratories emphasized as we move forward.

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): One of the things I’d like to see as we go forward is the laboratory not lose the momentum and visibility about its role and importance in health care. For too long we’ve been in the cellar or basement, rats running the wheel. The value of the laboratory has never been greater or more appreciated for those who have been able to deliver the services and the technology. We need to build on that and not let people forget that and be relegated back into a secondary role.

The second part of this is the big threat to the industry. PAMA is still on the books, and it is difficult. Starting this year, it would have been a tough year, and then COVID hit and nobody’s keeping score. But after COVID is over, PAMA’s going to be around again. And if the laboratory is not well established and recognized for its value, the dollars and cents are going to play a heavy hand on lab operations. Take advantage of the visibility and value you have brought to your systems, your hospitals, and your patients about the integral part the laboratory plays in health care, and continue to build on that role.

Dr. Crawford (Northwell): What we do right now is critical, even if we’re still licking our wounds as we recover services. Translating what Stan just said into action is a lift.

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): It’s a lift, but anything of value is a lift. It’s about executive leadership and more communications. This conversation itself could be the basis of a white paper on the value of the laboratory during the COVID crisis and how laboratories have overcome every challenge, every difficulty to deliver the goods and take care of patients. I don’t have a magic solution. I just don’t want us to lose the opportunity now when the visibility is there. And let’s make sure the visibility is positive rather than negative.

Let me add a wrinkle here. More times than not when laboratories become prominent in public media and public comment, we’ve seen events happen that have had negative consequences. Instead of the Pap mills being shut down, laboratories got CLIA ’88. Do we have the possibility now of a bad outcome because of the prominence people have put on testing, particularly when their understanding of that testing has been inadequately mediated by people who don’t know what they’re talking about?

John Waugh (Henry Ford): Truer words have never been spoken. When you talk about bad outcomes, immediately my mind went to Pap mills and people doing testing on their kitchen table. That’s where CLIA came from. But the outcome there is that the quality in a lot of our laboratories got better. A lot of the information that’s been in the lay press has been challenging. One of the good things that has happened is we learned about the importance of patient populations beyond inpatients and outpatients. Nursing home patients—when a professional athlete can get tested 24 times and grandma in the nursing home can’t get her first test yet, that’s a bit of a challenge. We learned more about the large disparities across a state and across the U.S. in resources and the ability to deliver. The easy and fast relaxation of state, federal, and CLIA regulations where you could do laboratory testing in a police station, at a car wash, anywhere you want. We’re going to have to flip back into a more regulated environment. I don’t think we’re going to be able to continue in that kind of a relaxed fashion and still talk about quality.

We learned in our laboratories that we had the ability to work remotely and do it at a high level. We also learned about the ability to change directions with speed. People said we need PCR testing, and then they said we need more PCR testing. They said, “Okay, we’ve got more PCR testing. What about antibody testing? Can you do antibody testing?” Yes, we can do antibody testing. “What about antigen testing?” We’ve had to chase a lot of different requests to compete and to prepare in different ways.

Susan Fuhrman, do you have opinions or thoughts about these long-term lessons and long-term sequelae of the pandemic for laboratories?

Dr. Fuhrman

Susan Fuhrman, MD, president, CORPath, Department of Pathology and Laboratories, OhioHealth Riverside Methodist Hospital, Columbus: The laboratory has come out of this looking pretty darn good in most places, particularly hospital and health system laboratories. We’ve taken on the challenge. We’ve flexed remarkably. We’ve developed great relationships with all kinds of people with whom we previously hadn’t had an opportunity to relate. And we don’t want to lose that momentum. This is a great opportunity for laboratorians and pathologists to stand up and take a bow, and we need to be out there to do it.

From my own standpoint, I can’t believe how fast my IT department can switch around orders and specimen types. And we’re going from dry swabs to wet swabs, from oral to nasal, on a dime. Things that took me months to get through they can do overnight, which makes me realize that it’s definitely a matter of priorities and resource allocation. These things are technologically possible and they can happen.

The same is true of resources. If I need something related to COVID testing, I just have to tell my story and it’ll happen. That’s another thing we don’t want to lose. We know now that these things can happen, and we need to be able to tell our stories well so that we don’t lose the attention we’ve had, which is good attention. We’ve shown what we can do and how key we are to the provision of medicine in this country. It’s a big opportunity.

Jim Crawford, give us your thoughts about how not to lose this momentum. You’ve given as much thought to this as anyone I know in the past three to five years.

Dr. Crawford (Northwell): It starts with your own corporate health system stakeholders, I would hope your payers, most certainly your medical practice community, and very definitely your consumers. So it’s a local and regional activity. That’s long before we go to Albany or Washington. Our relationships with our most immediate stakeholders are the foundation upon which we stand. Certainly the Compass Group represents that principle.

To address what Stan said about taking advantage of the visibility and value and building on it, my thinking is that this is a public relations challenge first. On the one hand it’s professional. Our medical colleagues and our corporate colleagues have learned more about laboratory medicine in the past five months than they thought was possible, and they’re still novices. That could continue.

But we are about to enter into the world of false-positives and false-negatives, so our relationship with our communities is critical if we’re going to navigate into the fall. This is not business; this is public relations. I can’t say I have a strategy for educating the broad public on false-positives and false-negatives. But it is upon us. I’d love to have people thinking about it, because we’re going to have visibility that could be upside or downside, depending on the way it plays out.

Some people have asked, Why doesn’t pathology and laboratory medicine have a Dr. Fauci? Greg Sossaman, would you care to answer that?

Dr. Sossaman (Ochsner): That’s a good question. Normally we rely on our professional organizations to play the national role. Traditionally we haven’t had any pathologists who have ascended the ladder from an administrative standpoint at the NIH or CDC—not to say that we couldn’t, but we haven’t. We’ve had high-profile pathologists in leadership positions in the AMA and in other areas, but not within the NIH. It’s possible we don’t have as much basic research on the pathology side that coincides with interest from the NIH and CDC.

Stan Schofield and Sterling Bennett, what is your take on why we don’t have a Dr. Fauci?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): We’ve never had something in pathology that impacted the whole population, and that’s where Dr. Fauci comes in. He is truly the expert. We’ve not evolved into epidemiologic, population studies, any of that. We have really smart people, but we don’t deal with public policy and/or populations or do research around infectious disease that lends itself to the promotional opportunity for an expert to go on TV or support the government as an expert. If we had a pathologic disorder or a cancer that was running everywhere, we might have someone like that. It’s just not normally our field of expertise. And pathologists have had supporting roles in infectious disease, microbiology, and virology but not top leadership roles. It just hasn’t evolved that way.

Yes, I sometimes have to remind people that Dr. Fauci cut his teeth in the AIDS epidemic, so he’s seen this movie before, including the political elements, although I don’t think, even in his wildest dreams, he would have thought he’d see the political elements he’s seeing today. Sterling Bennett, your thoughts?

Dr. Bennett (Intermountain): The short answer is we haven’t united behind someone and put that person forward as a spokesperson.

I’d like to echo what Norman Gayle said about the value of the community of the Compass Group and being able to get together and share the experiences we’ve had. It’s one thing to think we’re going through something alone and there’s something wrong with us because we have all these problems. But when we can see our peers who we know are expert in what they do and are individuals we try to model in our own practice and they’re experiencing the same things, there’s both a level of comfort there and an opportunity to confer with one another to get better ideas about what we can do to navigate this thorny path.