October 2018—CAP Press released in October the Color Atlas of Mycology, by Gordon Love, MD, D(ABMM), and Julie Ribes, MD, PhD. Its 388 pages hold more than 800 tables and images, with identifications verified by DNA sequencing (for images post-2009). Here, in an exchange with CAP TODAY, Dr. Love explains how this atlas stands apart from others in the Color Atlas series and from others on the market.

Dr. Love is chair of the Department of Pathology, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, and director of laboratories, University Medical Center, New Orleans.

Can you explain the concept of a field guide based on proficiency testing and why this field guide is useful in evaluating PT?

Can you explain the concept of a field guide based on proficiency testing and why this field guide is useful in evaluating PT?

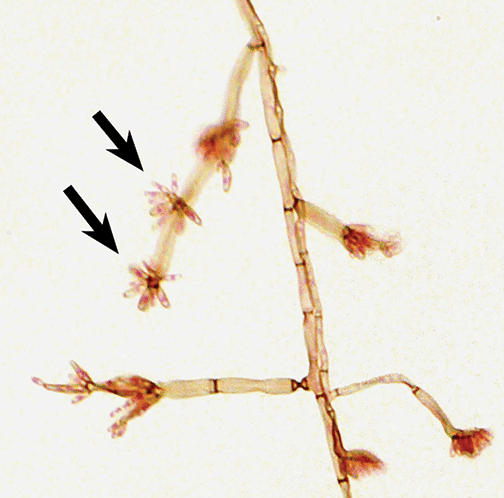

The Color Atlas of Mycology is based on proficiency testing results over a 16-year period in which fungal identification was guided by participant performance. The user-friendly presentations of images and text in the atlas show how to correctly identify as well as how to avoid misidentifying fungal challenges, whether proficiency testing or patient isolates. As an example, the use of Fonsecaea pedrosoi in FA-2002 resulted in an erroneous identification of Sporothrix schenckii by 47 participants. Both are dematiaceous (pigmented) molds that may form conidia along hyphae and conidiophores, but in the case of F. pedrosoi, elongated conidia may form asterisk formations (see image). Comparison of photographs make distinctions easier. This approach produced a mycology field guide that is uniquely suited to discuss the variations in fungal morphology that mycologists encounter in practice.

The process of identifying PT specimens should be identical to that of identifying routine clinical specimens. This atlas provides insights into the CAP mycology PT process. An advantage involves knowledge of previous challenges. The CAP Microbiology Resource Committee maintains a stored set of fungi for PT use. This stored set contains a restricted number of fungi that have been vetted by sequencing, with additions occurring relatively infrequently. A PT participant can easily review the 16-year history of mycology PT in this atlas but should realize that a new fungus could have been added recently. When entertaining any particular fungal diagnosis, distractors, as identified by previous PT, should be eliminated, and this thought process should be equally applicable to PT and isolates from clinical specimens.

From Fig. 96-3. Pattern of conidiation of Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Arrows indicate asterisk conidiation.

Your atlas is different in a few ways from previous atlases in the Color Atlas series. How so?

Most of the fungi, post-2008–2009, described in this Color Atlas of Mycology have been verified by DNA sequencing. This is in contrast to reliance on expert opinion and consensus as applied to morphology. Another way that the Color Atlas of Mycology differs from other Color Atlas titles is in the comprehensive use of PT data. All participant classifications for 16 years are reviewed. These identification decisions of PT participants defined the differential diagnoses. In the atlas, the adjacent comparisons of photographs of the correct and incorrect mold or yeast aid understanding. Other atlases in the Color Atlas series used photographs that had been distributed originally as PT challenges. The Color Atlas of Mycology is based on PT of organisms that live and then die and thus are unavailable for further study. Mycology PT examples after 2006 were documented by photographing the original challenges. For 2000–2006, the CAP did not keep microscopic photographs of challenges, but in some cases we were able to find photographs or glass slides in our personal collections.

Some important molds such as Coccidioides species have never been distributed for PT due to dangers in handling. We filled the gaps with yeast and molds collected in our mycology practices in order to make the Color Atlas of Mycology comprehensive. Some photographs were obtained from the pictorial library of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and others were used by permission.

Dr. Love

You write in the preface that the premise of this atlas is that morphologic identification will never become irrelevant even as diagnostic algorithms move to molecular or other nonmorphologic means. Can you elaborate?

As MALDI-TOF fungal databases become more comprehensive, fungal diagnosis is becoming faster and more accurate. But there will always be cases in which the molds or yeast do not identify. It would be in these cases that morphologic evaluation will continue to be necessary, and this atlas will help with that. It likely will remain good laboratory practice to correlate mold morphology with an automated result.

Can you describe the format of each section?

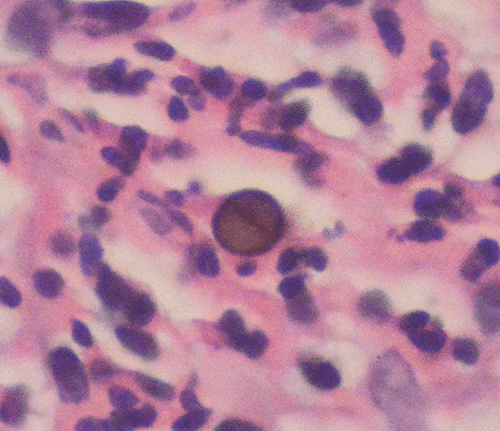

Each fungus is described in a standard format so the reader can easily find needed information to compare one fungus to another. An “essential facts” section describes the major aspects of identification as well as medical significance and ecology. Photographs of colonial and microscopic morphology follow. A taxonomy section describes changes in classification that have been prompted by the advent of DNA sequencing. For instance, Penicillium marneffei is now classified as Talaromyces marneffei. The Color Atlas of Mycology uses parentheses to indicate new and obsolete classification, as in “Talaromyces marneffei (formerly Penicillium marneffei),” to make these changes easier to follow. PT results from 2000 to 2016 are illustrated with abundant photographs that compare incorrect identifications to the challenge fungus. A final disease section describes disease manifestations with photographs of tissue and cytology presentations. Periodic “A closer look at” sections go into detailed examination of varied topics, such as the recommendations for mycology laboratories to identify Candida auris. This atlas has useful information for the bench medical technologist as well as for pathologists and infectious disease practitioners. An example of the extensive histopathology discussions is a muriform body from a case of chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi (see image).

From Fig. 87-3. Muriform body in chromoblasto-mycosis caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi.

Is there anything like this atlas on the market?

The 111 fungi described in the atlas cover almost all fungi in the CAP Master Lists of fungi and yeast. The Master Lists are useful documents that the CAP has developed over years to contain the fungi most likely to be associated with disease or to be otherwise encountered in the laboratory, such as saprophytic fungi often seen as culture contaminants. While it is possible that fungi not represented in this atlas may infect profoundly immunosuppressed patients, this text should reflect the workload of most medical mycology laboratories. The approach of the Color Atlas of Mycology in using differential diagnoses constructed by mycologists represents a new and unique application of PT data that no other mycology text incorporates. The hundreds of color photographs help with understanding the differences between look-alike fungi to improve the practice of mycology.

To order, go to cap.org, “Shop” tab, or call the CAP at 800-323-4040 option 1 (PUB226). CAP member price: $144; for others: $180. Ebook: $130 at ebooks.cap.org.