Autopsies show many faces of COVID-19

Anne Paxton

June 2020—“Sudden” and “global” are descriptors that seldom appear in tandem, especially in relation to disease epidemiology. But they both fit the COVID-19 pandemic, which has left the health care world reeling.

“COVID-19 has infected the entire planet pretty much all at once,” says Alex K. Williamson, MD, chief of autopsy pathology and director of the regional autopsy service for Northwell Health, the largest health system in New York State. “Never before have I seen a single disease stop the world.”

For autopsy services, it has created exceptional challenges, and, in watching the crisis balloon, Dr. Williamson realized that autopsy pathologists would have to cope with a serious information gap. “We were all facing the unknown with how to handle morgue operations and autopsies involving COVID. And we were trying to figure things out in isolation. There’s no playbook for what we’re going through.”

He decided that an ad hoc autopsy pathologist listserv to facilitate group discussion would start to address the problem, so he brought together an international consortium of autopsy pathologists. Its goal: sharing the information that its members have gleaned about COVID-19 from the autopsies they perform. “I thought it would be a good idea to bring everybody together so we could figure out COVID-19 with aggregate, communal knowledge.”

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration surprised and baffled many autopsy pathologists by issuing in March a guidance advising against performing autopsies without strong indications to do so, says Dr. Williamson, who spoke with CAP TODAY on April 29. In response, institutions limited the procedures or halted them indefinitely.

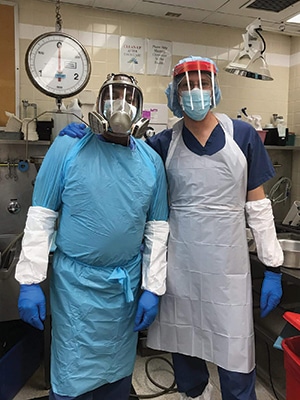

Dr. Williamson (right), with Devon Betts, autopsy assistant/morgue attendant. “We can’t and shouldn’t autopsy every COVID-19 death,” Dr. Williamson says, calling it an impossibility and dangerous. “But what we are doing is sampling a subset of patients across the spectrum.”

“A really important aspect of this group’s coming together,” Dr. Williamson says, “was making sense of the ambiguous OSHA guidelines.” When the pandemic began, “Everyone was scared. We just didn’t know what this thing is. And as we started talking to each other through forums like the listserv, more and more of us realized that the OSHA guidance was ill-informed.”

The guidance has since been retracted. “I was one of the earliest, most outspoken critics of that policy on the listserv,” Dr. Williamson says. “And others, through having this forum to share ideas and discuss, realized that if you have the right resources, such as a negative-pressure autopsy suite and appropriate personal protective equipment, and the training and skills to do infectious autopsies, we need to be doing them.”

The number of participants on the listserv, which launched in late March, rose to 180 by early May. Dr. Williamson’s surveys of participants show that the percentage of people on the listserv responding to the surveys who had done an autopsy on a COVID-19 decedent grew from around 10 percent to nearly 50 percent between March and May.

From a postmortem care standpoint, there are two main aspects to the virus, Dr. Williamson says. “There’s the morgue management of an increased death count, and there’s the importance of performing autopsy to understand this disease while ensuring the autopsy is done safely.”“Many people who have the disease have diffuse alveolar damage, but in other people COVID-19 forms blood clots. We’re also learning on the clinical side, and confirming it by autopsy, that this disease is more aggressive in those with underlying or preexisting conditions,” primarily high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, and obesity.

“In the clinical setting and in autopsy,” he says, “I have not yet seen this virus kill a truly healthy individual.” Most people who get COVID-19 aren’t in the hospital, Dr. Williamson notes. “They definitely aren’t on a ventilator and they aren’t dying. But we in autopsy pathology and all medical personnel are trying to figure out how to treat those who have a bad course. What is it about that population of people who come into the hospital, go on a ventilator, and then eventually die? What can we learn about that disease process, through autopsy, that can help those who have yet to contract this disease?”

One of the many mysteries yet to be unraveled involves the apparent mismatch of ventilation and blood oxygenation, Dr. Williamson says. So far, he has performed autopsies only on those who had no ventilator support or who had been on a ventilator only for days. “But it’s important that we sample patients across the spectrum of duration on a ventilator as well, so that we can learn why there is a ‘clinical disconnect’ between mechanical ventilation and oxygen levels in the blood,” he says. “As is the case with any medical intervention, it’s also important to assess if an intervention such as prolonged ventilator support is causing or contributing to tissue injury.”

A topic that comes up often on the listserv is how many autopsies should be performed. “We can’t and shouldn’t autopsy every COVID-19 death,” Dr. Williamson says. “That’s an impossibility and it’s dangerous. But what we are doing is sampling a subset of patients across the spectrum. It’s important to examine different ages, different underlying conditions, and different lengths of hospitalization and ventilation.” Through that process, “We hope we’ll be able to obtain a better understanding of what this disease is, how it affects us, and what we can do to better manage it.”

As one example of how the listserv has helped change approaches to maximize the autopsy’s usefulness, Dr. Williamson says, “We know that people with COVID-19 have a higher incidence of blood clots, so some who have the training are doing complete exams of the deep leg veins at autopsy to make sure there are no hidden blood clots that we wouldn’t see in a normal autopsy approach. That’s an example of how we are modifying our autopsy technique to learn more about the disease. It’s kind of a feedback loop with the active practitioners, the autopsy pathologists, doing the work, and our experience informing the work we all do moving forward.”

At autopsy, pathologists are observing clots filling a vessel that are visible to the naked eye as well as those that require a microscope to be seen. “We are seeing microscopic blood clots in some organs,” he says. But they are not as prevalent as initially feared, in his experience. “Early on, there was a report that COVID-19 patients had all these microscopic thrombi forming in the lungs and the kidneys. I haven’t seen that in a majority of the cases I’ve examined. We’re still exploring that as a community, but the microscopic blood clots don’t seem to be a salient feature of the disease pathology.”

The “cytokine storm,” an escalated immune response, is a known feature of some COVID-19 infections. But as a humoral response, circulating in the blood, it cannot be seen at autopsy. “What we can see are the effects of that cytokine storm if they have anatomic manifestations. I may see inflammation of the heart or lung under the microscope, for example. If the cytokine storm sets up a blood clotting state, I will see those blood clots. So autopsy can corroborate the idea of the cytokine storm but it can’t visualize the humoral activity of that cytokine storm,” he explains.

Using electron microscopes that allow magnification powerful enough to view viruses, autopsy pathologists have been viewing sample tissues removed at autopsy, a survey of the listserv confirms. Dr. Williamson has seen probable virus in the lung of at least one of the decedents he examined, and studies have reported finding virus in various other tissues and organs throughout the body. “It’s conceivable that this virus would spread throughout the body during the viremic stage of infection and would deposit in the various tissues,” he says. “More definitive results from a larger number of autopsies would confirm this. But we are leaning toward believing that this virus disseminates throughout the body and implants in the colon, in the kidney, in the lung.” More clarification of that is needed, he says.

A survey of listserv members found that most people are following the recommended autopsy guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Williamson reports—although since testing resources are limited, if a person has a positive antemortem test, such as with a nasopharyngeal swab, a postmortem swab would not add anything and would not necessarily be taken at autopsy.

However, he has found that some pathologists are obtaining postmortem swabs from the lung and collecting tissue to freeze for later analysis. In addition, if someone has suspected COVID-19 and dies but there was no diagnosis in life, “I do think the postmortem nasopharyngeal swab serves an important purpose for epidemiology and for that autopsy.”

Most basically, it’s important to emphasize, he says, that autopsies are confirming that almost everybody dying with COVID-19—“and I believe probably everybody”—has a preexisting condition that renders them vulnerable to the virus’ lethality.

The number of autopsies that NYU Winthrop Hospital conducts each year hovers around 100, says chair of pathology and laboratory medicine and autopsy director Amy Rapkiewicz, MD, who spoke with CAP TODAY on May 5. But when her hospital admitted its first COVID patient March 3, that changed. Based on the OSHA recommendation, “The administration was not in favor of us doing autopsies right from the get-go.”She views a COVID autopsy as no different from an influenza autopsy. “We’re board-certified forensic pathologists and our autopsy suites are negative-pressure. We use PPE. But we created a specific COVID protocol and some of it came from talking to Alex and getting great information from other people on the listserv.”

After her department re-petitioned the administration, “They allowed us to do two COVID autopsies a week.” This agreement came because of the inquiries she and her colleagues received (and kept track of) from the critical care physicians. “We have a good relationship with them, and they were emailing us saying, ‘We ventilate the patients but they’re still hypoxemic. What are you seeing at autopsy?’”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management