Karen Titus

December 2021—There are success stories. There are overnight success stories. And then there are things that just seem to happen overnight—minus the success.

In the midst of chronic discontent over the use of a race coefficient in equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate, one San Francisco hospital sought to make a change. The hope was to help end disparities in health care, such as lower kidney transplantation rates in Black people with chronic kidney disease.

The change at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital was pushed by what Neil Powe, MD, MPH, MBA, calls “a very small group of faculty and trainees lobbying the lab, unbeknownst to others.” The lab reported two values, using the eGFR equation with and without the race coefficient, but assigned “high muscle mass” and “low muscle mass” to the two values as a way to step around the troubling race component.

Dr. Powe, the hospital’s chief of medicine, doesn’t mince words when he considers how the change was made. “And it stereotyped ethnic groups even more,” he says.

Despite all the talk and desire to do things better—which reached a nationwide crescendo in the summer of 2020—there remained misapprehension about the role race has played in determining eGFR. Change was needed, says Dr. Powe, who is also the Constance B. Wofsy distinguished professor and vice chair of medicine, University of California, San Francisco. “But we needed a pathway to replacement.”

That path has opened up, recently and widely, with a new eGFR equation recommended by the National Kidney Foundation-American Society of Nephrology Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease (Delgado C, et al. Am J Kidney Dis. Published online ahead of print Sept. 23, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.08.003). Dr. Powe co-chaired the task force, along with UCSF colleague Cynthia Delgado, MD, associate professor and associate chief of nephrology–clinical operations, Department of Medicine, UCSF, and nephrology section, San Francisco VA Medical Center.

The equation is one of three recommendations the task force made:

- Immediate implementation of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable. As the authors note, the equation “does not include race in the calculation and reporting, includes diversity in its development, is immediately available to all labs in the U.S., and has acceptable performance characteristics and potential consequences that do not disproportionately affect any one group of individuals.”

- National efforts to increase routine, timely use of cystatin C, especially to confirm eGFR in adults with or at risk for CKD. Combining creatinine and cystatin C is more accurate, the task force notes, and supports better clinical decisions than using one filtration marker alone.

- Further research, aimed at eGFR estimation with new endogenous filtration markers and interventions to eliminate race and ethnic disparities in care.

The task force held 40-plus sessions to assemble and review data and evidence; in 16 sessions it heard testimony from 97 experts. It also took testimony from the community at large, including students and trainees; clinicians, scientists, and other allied health professionals; and patients, family members, and others—450 people in all.

Dr. Neil Powe and Dr. Cynthia Delgado, co-chairs of the task force that recommends use of the CKD-EPI creatinine equation refit without the race variable. “I want this work to stand,” Dr. Delgado says of the task force recommendations. “And I want this work to reflect that this is not a perfect test.” (Photo: Cindy Charles)

The recommendations are based on the work of another group (Dr. Powe, among others, was part of both groups), the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI), which formulated and cross-validated new GFR estimating equations without a race coefficient (age and sex are the only demographic factors), comparing them to currently used CKD-EPI equations (Inker LA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385[19]:1737–1749). The group used two data sets to develop current equations. One was from the CKD-EPI 2009 for eGFRcr (10 studies, 8,254 participants, 31.5 percent Black); the other from CKD-EPI 2012 for eGFRcys and eGFRcr-cys (13 studies, 5,352 participants, 39.7 percent Black) for both serum creatinine and cystatin C. They then compared the accuracy of the new eGFR equations to measured GFR in a validation set of 12 studies, seven of them new (4,050 participants, 14.3 percent Black).

Explains lead author and task force member Lesley Inker, MD, MS: “The work we did allowed the task force to come to this conclusion. Recommendation No. 1, of the CKD-EPI equation refit without the use of race, is the equation as reported by the New England Journal on the same day.” Dr. Inker is director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center and of the Kidney Function and Evaluation Center, Tufts Medical Center, and associate professor of medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine.

Among the criteria upon which the NKF-ASN task force’s recommendations were based were key elements of interest to labs, she says, including widespread availability of the filtration marker in all clinical laboratories, standardization of the assays, and high-throughput analyzer capability. The new approach would need to be relatively easy for laboratories to adopt.

Any new approach the task force developed, moreover, would need to be based on diverse populations. Of 12 approaches that did not include race as a variable, for example, seven were developed using populations that included no Black individuals. Among six approaches that were developed in a diverse population, the task force chose five for more in-depth analysis.

The task force also took into account performance in external validation (in terms of bias, precision, and accuracy), as well as potential long-term consequences.

“I think they did a very good job of rolling this out in a comprehensive way,” says Melanie Hoenig, MD, associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Renal Division, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The key reports “all came out online at once,” she says. “And the National Kidney Foundation’s website, kidney.org, updated their calculators at the same moment.” She also lauds the comprehensive supplementary data included as part of the task force report.

All this is aimed at improving a measurement that can seem dicey from a clinical standpoint.One may be the loneliest number, but a collateral point might also be true: One number alone may not be sufficient. A single eGFR value, even calculated with the best of all possible equations, is not the beau ideal. Many physicians, Dr. Hoenig says, “probably don’t even remember that it’s an estimate. They’re just looking for a number to help guide them in terms of medication.”

Nevertheless, eGFR has pulled the lion’s share of attention, even more so with the latest reckonings on the race coefficient. Given that spotlight, observers are hoping the new equation and recommendations will change not only what labs and clinicians do but also how they talk about what they’re doing, with one another and with their patients. Those working to bring about change dug deep; the hope is that the change will be equally seismic.

Dr. Delgado runs the low kidney function clinic as well as the dialysis unit at the San Francisco VA. The hospital intends to implement the new equation; it already offers cystatin C in-house.

In one regard, the new equation may not change her day-to-day practice significantly, she says. “I have a tendency to follow change in kidney function,” she says. “And there are so many other things that one evaluates in a person when you’re trying to decide whether they’re going to need dialysis,” including metabolic abnormalities, proteinuria, and albumin in urine.

But on an equally practical level, she continues, “this change addresses any questions and ambiguity” that have bubbled up with the current estimating equation. The race coefficient “didn’t make it easy to have a dialogue with patients.”

In that regard, the new eGFR equation might serve almost as a type of medical talking stick. “It’s a moment for patients and practicing physicians to have a better relationship because it clarifies the dialogue a little bit better,” Dr. Delgado says. “Patients are no longer going to be apprehensive or worried that their kidney function estimation and their [treatment] plan are going to be driven by how they look. As a clinician, that’s a great thing.”

The new eGFR equation looks familiar, and even similar to the CKD-EPI equation currently in use—though it lacks the race coefficient—“but it’s different,” says Dr. Hoenig. “There are lots of little parts of it that are different. The formula itself is really complicated, with several exponents.”Many clinicians won’t dip far into the backstory of how the new equation was developed, Dr. Hoenig says. “They’re looking for the lab report, they’re looking for the creatinine, and then they’re looking for whatever the lab says is the estimated GFR.”

Nevertheless, she suggests it’s worth peering more closely at the work behind the new formula. Fig. 1 in the New England Journal study provides a strong visual of how the current and the new creatinine and creatinine-cystatin C equations perform in Black and non-Black populations. It also looks at the performance of the current cystatin C equation, alone, in both groups.

The current CKD-EPI works well for non-Blacks. “It doesn’t mean every single person is on the line of identity, but on a population level the formula works well,” Dr. Hoenig says. For non-Blacks, the P30 is 89 percent; that is, 89 percent of participants are within 30 percent of their true GFR. (In Dr. Hoenig’s experience, “People are shocked by that info: This eGFR is only within 30 percent up or down of the number you’re giving me? But providers don’t want that nuance. Primary providers have increasingly challenging work addressing complex medical conditions,” she says, “and are grateful for dosing guidelines linked to a single eGFR value.”)

Correct classification shows how many people fall into the correct stage of CKD predicted by the eGFR, Dr. Hoenig continues. For non-Black participants, that figure is 69 percent.

For Black people, using the current formula with the race coefficient results in more dismal numbers. The P30 is 85 percent, and the correct classification is 63 percent.

The authors also looked at the impact of simply removing the race coefficient from the current CKD-EPI formula and keeping the other elements the same. Simply put, it doesn’t work.

Dr. Hoenig

“This is the argument that many have been making—that you can’t just drop the race coefficient,” Dr. Hoenig says. “Because then you will misclassify more people.” For Black participants, the correct classification falls to 59 percent when the coefficient is dropped; for non-Blacks, the correct classification is unaffected and remains at 69 percent. “Honestly, none of these numbers are actually very good.”

The new formula yields results that fall in between those two approaches. For Black participants, the P30 is 87 percent. Correct classification is 62 percent. For non-Black participants, P30 drops to 86 percent; correct classification is 67 percent.

Bias (the median difference between measured GFR and eGFR) for Black participants is +3.6 milliliters per minute per 1.73 square meters with the new equation, which falls in between the numbers for the current equation (bias: –3.7) and the current equation dropping the race coefficient (bias: +7.1). (A positive sign indicates underestimation of measured GFR; a negative sign, overestimation.) For non-Black participants, the bias in the new equation is now –3.9; in the other two equations, it’s –0.5. “But, on the whole, for an individual it does not perform very differently from before,” says Dr. Hoenig. “And now we have a much better profile for the Black participants.” On average, the new equation is an improvement, she says.

Dr. Inker

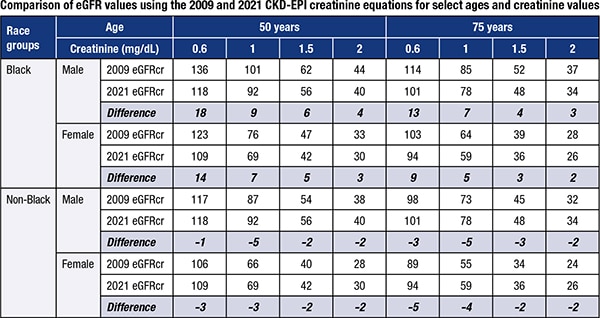

The new eGFRcr equation has similar overall performance to the current equation, but its main advantage, Dr. Inker says, is that it does not disproportionately affect any one group of individuals. The true GFR has not changed, even though the reported value might differ—which is important for patients and health care professionals to remember. “In general, the new eGFR values will be slightly lower in Blacks and slightly higher in non-Blacks than previously reported values, and the changes will be greater for younger patients and those with higher levels of GFR,” Dr. Inker says (see table).

Dr. Hoenig applauds the supplemental material that identifies the makeup of each cohort that was used in equation creation. “One of the things that’s always been murky—since race is a social construct—is how participants were assigned.”

When the MDRD GFR equation was developed, “that notion of how people were assigned to each group was not generally considered,” Dr. Hoenig says. When the current CKD-EPI was developed, things weren’t much better. “You cannot find that information when you read that report.” To do so requires pulling the 16 studies in the development portion and the 10 in the validation cohort, “and then trying to figure out how they recruited patients.”

Dr. Hoenig extols the transparency by everyone involved. Those who developed the new equation “pulled the curtains back on that, which I think is helpful.”

Fig. 1 in the New England Journal article provides similar insight into how adding cystatin C to the various equations performs. Similar patterns of improvement are evident as well. Adding cystatin C to creatinine improves the accuracy of the estimated GFR for both groups, with less difference between groups.There was no need for a new equation that included only cystatin C, since the current one does not use a race coefficient. The biggest change may simply be the push to use it more in combination with creatinine so the result is more accurate, Dr. Inker says.

For the vast majority of laboratories, cystatin C is a send-out; it will require what Dr. Hoenig calls “activation energy” to bring it in-house.

There is a “very real logistical hurdle to incorporating cystatin C,” agrees Jonathan Genzen, MD, PhD, chief operations officer, ARUP Laboratories, and associate professor (clinical), University of Utah Department of Pathology. It can be performed on many automated analyzers, “so I would not describe it as a particularly esoteric test. Rather, it is not yet available on the extensive array of automated platforms that you would want at this point.” Ideally, it would be performed on combined chemistry-immunology instrument clusters so that cystatin C and creatinine can be performed at the same time without specimens having to be distributed among laboratory sections, he says. “But cystatin C is not yet in widespread use, and it adds significant cost.”

There is a “very real logistical hurdle to incorporating cystatin C,” agrees Jonathan Genzen, MD, PhD, chief operations officer, ARUP Laboratories, and associate professor (clinical), University of Utah Department of Pathology. It can be performed on many automated analyzers, “so I would not describe it as a particularly esoteric test. Rather, it is not yet available on the extensive array of automated platforms that you would want at this point.” Ideally, it would be performed on combined chemistry-immunology instrument clusters so that cystatin C and creatinine can be performed at the same time without specimens having to be distributed among laboratory sections, he says. “But cystatin C is not yet in widespread use, and it adds significant cost.”

Roughly two percent of U.S. labs perform cystatin C in-house, says Greg Miller, PhD, professor of pathology, co-director of clinical chemistry, and director of pathology information systems, Virginia Commonwealth University, who was also a member of the NKF-ASN task force. Because it’s a send-out test for so many, coordinating results to perform the new eGFRcr-cys equation might present another challenge to labs, at least from an IT perspective, he says.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management