Anne Paxton

October 2019—You may not be curling up next to the fire with a cup of hot chocolate to read your copy of the new Digestive System Tumours, part of the World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Series. You’re more likely to have it sitting nearby at work with dog-eared pages and a cup of coffee on it, says Ian Cree, MB ChB, PhD, head of the WHO Classification of Tumours Group and editorial board chair of the latest and fifth edition. Still, as essential reference guides in medicine go, the freshly minted 635-page tome, released worldwide in June, is a ravishing picture book.

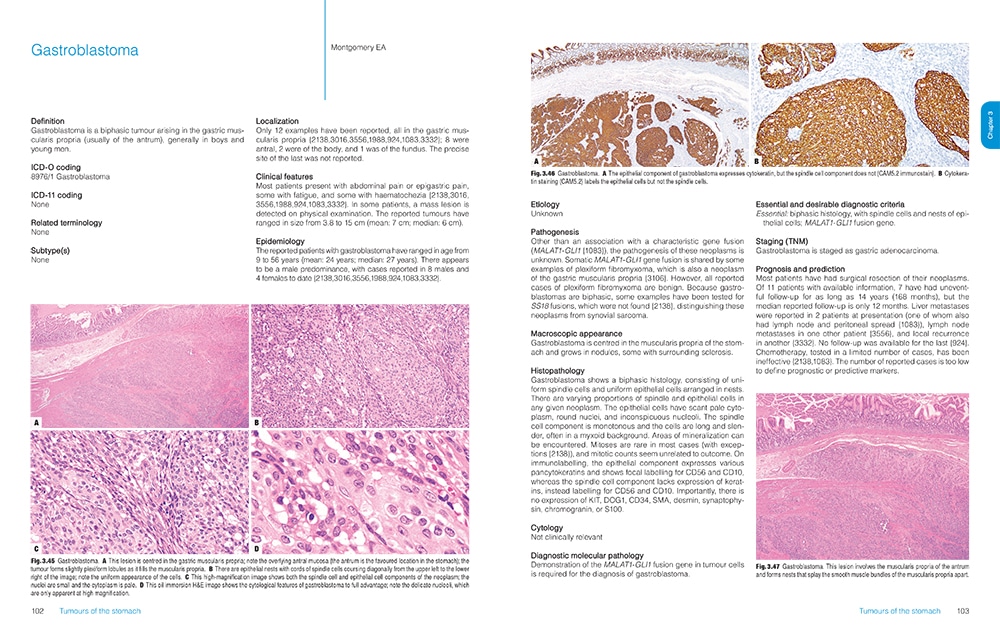

Featuring more than 1,000 high-resolution color graphics, Digestive System Tumours, the first volume of the fifth edition of the WHO series known as the Blue Books, brings a noticeable improvement in image quality and graphic design over the fourth edition, published in 2008. The book’s two-column layout, replacing the former three-column design, allows for enlarged images throughout. And this book is the first to be produced in both a print version and an online subscription version that includes whole-slide imaging.

Dr. Washington

More important, the book has been rewritten and reorganized to incorporate new tumors, new information about how each tumor behaves, and other significant advances in classification since the 2008 edition. “The new edition was a worldwide, collective project that brought together pathologists from Asia, South America, Europe, North America, Australasia, and Africa to collaborate using the best available evidence and practices,” says Mary Kay Washington, MD, PhD, professor of pathology, microbiology, and immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and a standing member of the WHO series editorial board.

Now that the new book is available, the WHO board hopes people can start using the terminology immediately, Dr. Washington says.

Classification is important because it creates the international standards that underpin diagnoses of all tumor types in all cancers, says Dr. Cree, who is a pathologist with the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, publisher of the WHO Classification of Tumour Series. “It means that you can compare data worldwide from different health care systems very easily. If you have a stomach cancer in the U.S. or in Europe or in Japan, it will be the same. You can therefore compare clinical trial results and be confident that patients are getting similar, if not identical, diagnoses from pathologists across the world.”

The fourth edition of the WHO series set a whole new standard and raised the bar considerably from the third edition, Dr. Cree says. “And we are honestly trying to do the same with the fifth edition.” The new online subscription feature, for example, is intended not only to make user access easier but also to show significantly more content. “We have a whole-slide image for each diagnosis in the book. Whole-slide images allow us to get an overview of the entire section of the slide right down to the individual cells and see what is going on.” In addition, each paper in the book has a direct online link to the evidence that underpins the paper, he notes.

The large amount of genomic information in this new edition of Digestive System Tumours reflects how necessary molecular data are becoming in diagnosing some tumors, though by no means all, Dr. Cree says. “There is an increasing amount of information that is of very considerable use. If you look at cancer incidence across the U.S., you would find that the bulk of patients have tumors within the top 10. Those are the ones we tend to use quite a bit of molecular information with.”

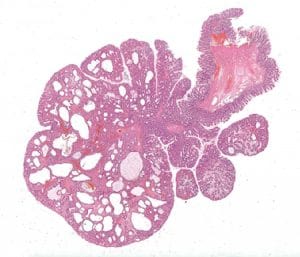

From the chapter “Genetic tumour syndromes of the digestive system,” juvenile polyposis syndrome.

Gastric juvenile polyps.

Colonic juvenile polyp. An example from a patient with juvenile polyposis syndrome, characterized by an increase of the stroma and cystically dilated crypts.

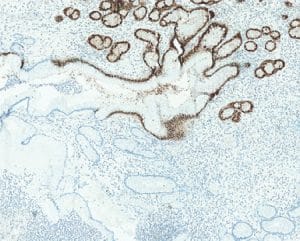

Gastric juvenile polyp. SMAD4 loss in a polyp from a patient with a germline SMAD4 mutation.

The molecular data are also proving that appearances can be deceiving. “We are finding that certain tumors turn out to be the same genetically despite the fact that they look sometimes quite different. We are finding others that look the same but are actually quite different. So the data are increasing our ability to classify and therefore to diagnose,” Dr. Cree says. Among other milestones, this edition of Digestive System Tumors is the first in which certain tumor types are being described as much by molecular phenotype as by histological characteristics. “We have some tumor types where, without the molecular information, you cannot make the diagnosis. It is certainly a new departure for us to put together that information with the standard histopathology.”

The incorporation into the book of the many advances in understanding the genetic drivers of tumors is one of the book’s most important new features, Dr. Washington says. “We probably aren’t to the point of using molecular classification for most GI tumors yet, but we are including a lot more information on the basic genetics.”

A team effort was behind the classifications in the fifth edition of the WHO series. “One thing we did is set up an editorial board. We didn’t have one before,” says Dr. Cree, who asked that CAP members be included on the board when he was appointed to lead it. “We have pathologists and, increasingly, other clinical colleagues on those boards and they consider the evidence that is collected by up to 200 authors for each book. I hope we have not made the team work too much harder, but we have certainly made them work faster. The writing phase is done much more quickly, we are doing a lot of work in parallel to speed up the production phase, and we are using a bit of process management to ensure we have the optimal way of doing the book.”

From the chapter “Tumours of the stomach.” Intestinal-type adenoma. This adenoma is accompanied by intestinal metaplasia on the right side and shows prominent tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes; a subset of such adenomas are microsatellite-instable.

A key change in this edition is the classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). “We had an expert group that met in November 2017 to solve some of the consistency problems that existed between the volumes in the classifications of NENs,” Dr. Cree says. “Within the digestive system, you obviously have quite a few different organs. We were able to ensure that the neuroendocrine neoplasms were dealt with similarly in each of those organs as a result. We also put soft tissue tumors and hematolymphoid tumors in separate chapters at the end. Having designated chapters let us treat the whole subject of those particular tumor types better.”

Some information issues, the editorial board found, have proved to be more difficult to address. Pathologists sometimes disagree on whether to change terms that are in day-to-day use, and there are certain more convoluted terms that the board would prefer to replace, Dr. Cree says. “We have certainly made changes to the names of tumors where we felt it was necessary, but we were aware there are multiple names in use across the world for some tumor types.” So, in many cases, “we have said what we feel is an acceptable terminology and what is not recommended for being outdated.”

The editorial board did agree to make changes in definitions in some terms relating to stomach cancer, but the process was not simple. “We try to achieve a consensus by having the expertise that we need in the room. You talk about the evidence and sometimes your decisions are fairly straightforward and sometimes they are not. If there is uncertainty, then what we now do is express that. If we don’t know what something is, we say that.”

Despite the value of the books in helping with diagnosis, Dr. Cree says, they can’t quite compensate for the small number of pathologists in the world and the increasing workload in histopathology, especially in high-income countries over the past 10 years. “We have the problem of how we handle the increasing complexity of what we’re being asked to do. Largely that is because it is no longer good enough to give a diagnosis. We hope the classification helps by making it clear what is required and what is not required and what the standards are.”

The classifications, he adds, are used by the International Collaboration on Cancer Reporting to produce synoptic reports; the CAP also uses the reporting templates. “Those templates help enormously to make sure patients get all the information they need from pathologists. I think that is extremely important today.” For the CAP cancer protocols as well, Dr. Washington says, “we will be looking at the new histology terms, and if there are any critical differences, they will be incorporated on the rolling update schedule. Minor differences will be incorporated but not until the next scheduled release of the protocols.”

WHO editorial board expert member David S. Klimstra, MD, chair of the Department of Pathology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, has been involved with the GI books and the endocrine organ books through three editions of the WHO series, spanning roughly 20 years. While the digestive system tumors include everything from the esophagus, stomach, intestines, colon, and liver to the pancreas and gallbladder, he worked most closely on pancreas, liver, and the neuroendocrine system.

Dr.Klimstra

The classification of liver tumors, especially bile duct tumors, has changed in this edition, he says, in ways that will affect patient treatment. “We made an effort to bring together a group of diverse tumor types that are now felt to fall under one broad category instead of several smaller categories, so that is an important change. Bile duct cancer classification has been condensed and simplified. Many variants have been collapsed into essentially two major categories of cholangiocarcinomas. This will make it a lot easier for pathologists to classify these kinds of liver cancer because the criteria to distinguish all previous variants were not well accepted.”

The classification of neuroendocrine tumors throughout the GI tract, which has been updated and standardized, is also significant, Dr. Klimstra explains. “We discovered over the past decade that simple classification into three grades that distinguish well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors grades 1 and 2 from poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma grade 3 is actually wrong. In the current book, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors have three grades—G1, G2, and G3—that correlate with increasing proliferative rate and tumor aggressiveness. The poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas are a completely separate entity; they have a very poor prognosis and we aren’t even grading them anymore. This has allowed us to recognize a different spectrum of NENs than previously and to tailor the treatment to the specific genetic and pathologic subtype that the patient has. It applies to every organ in the GI tract, liver, and pancreas.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management