Amy Carpenter Aquino

March 2019—Unlike high-count monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis, low-count MBL has a limited chance of progression to CLL and thus there is no need for follow-up. And a definitive diagnosis of T-cell large granulocytic leukemia requires demonstration of clonality. Those and other points were made in a CAP18 session on practical challenges in peripheral blood evaluation.

Carla S. Wilson, MD, PhD, professor of hematopathology, and Devon S. Chabot-Richards, MD, associate professor of hematopathology and molecular pathology, Department of Pathology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, presented seven of their cases illustrating the challenges of peripheral blood smear evaluation, three of which are reported on here (with others to be published in April). Drs. Wilson and Chabot-Richards are medical directors at TriCore Reference Laboratories, Albuquerque.

‘You should not be doing your differential diagnosis at the feathered edge; the

morphology is not good enough.’ —Carla Wilson, MD, PhD

The key to an accurate peripheral blood examination is a good-quality peripheral blood smear with different zones that can be evaluated, Dr. Wilson said. “The lateral edges are where large cells such as monocytes, immunoblasts, immature cells, and blasts are often deposited.” The feathered edge of the blood smear is where platelet clumps will be seen, as will sometimes malignant cell clumps and microorganisms. “You should not be doing your differential diagnosis at the feathered edge; the morphology is not good enough,” Dr. Wilson said. Instead, do your differential counts and observe morphology in the monolayer or thin area, where the cells are nicely separated. “A systematic approach is best where you scan at low power to look at the overall number of cells and types of cells and then go to high power for assessment of red cell, white cell, and then platelet appearance,” she said.

The first case is that of a peripheral blood smear Dr. Wilson examined on a 58-year-old woman with no significant medical history who visited her physician eight months after a health fair screening that found an elevated white blood cell count with increased lymphocytes.“We found on her CBC that she had a mild leukocytosis due to a lymphocytosis,” Dr. Wilson said. “The rest of the counts were normal.” The lymphocytes were 40 percent of WBCs, with an absolute lymphocyte count of 4.4 × 109/L.

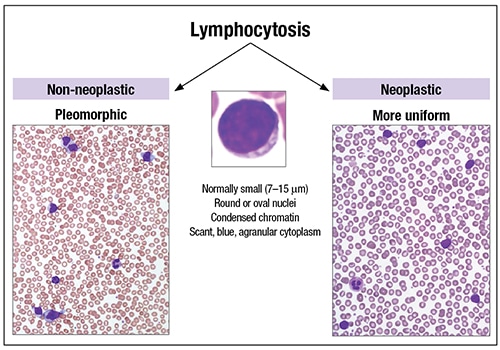

Dr. Wilson described normal lymphocytes as small, with round or oval nuclei, condensed chromatin, and scant, blue, and agranular cytoplasm.

A lymphocytosis can be reactive (non-neoplastic) or neoplastic (Fig. 1). Non-neoplastic types have more variability in cell sizes and shapes, and more pleomorphism, than what one usually sees in neoplastic processes, which tend to be more uniform, Dr. Wilson said. “But there are exceptions.”

Non-neoplastic lymphocytosis can be further divided into nonactivated and activated types.

Fig. 1

“An important cause for nonactivated lymphocytosis that needs to be recognized nowadays is Bordetella pertussis or whooping cough,” which is increasing because of under-vaccination in many communities, Dr. Wilson said. A significant fraction of small lymphocytes with cleaved or convoluted nuclei and scant cytoplasm provides a clue to identification of this disorder.

Another clue: Infants and young children present with very high WBC counts. “The pertussis toxin decreases the L-selectin on the surface of T-lymphocytes, so they don’t migrate through vessels into tissue. The lymphocytes build up within the vessels and become a lymphocytosis.”

The disorder is trickier to spot in adults, she noted, because two-thirds of adults will have normal WBC and lymphocyte counts by the time they seek medical attention.

In non-neoplastic lymphocytosis with activated lymphocytes, the lymphocytes tend to be much more variable in appearance with a greater number of large cells. Downey type II lymphocytes are intermediate to large cells with smudged chromatin, inconspicuous nuclei, and abundant pale blue cytoplasm with a rim of basophilia, which are associated with viral infections, particularly infectious mononucleosis from Epstein-Barr virus infection. “If you have a lymphocytosis in a 15- to 24-year-old in the U.S., with activated lymphocytes, make sure you exclude EBV-associated infectious mononucleosis, even if the heterophile antibody [monospot] test is negative. Continue evaluating with EBV-specific antibody testing,” Dr. Wilson advises.

In neoplastic lymphocytosis, B-cell neoplasms are much more common than T- or NK-cell neoplasms. The differential for B-cell neoplasms depends on the patient’s age, clinical symptoms, morphologic appearance, and physical exam. “Look for laboratory findings, such as paraproteins or cytopenias,” she said. Composite findings will help determine which cases should be evaluated by flow cytometry and other ancillary testing.

‘The big question is, when do we run flow cytometry on our patients with a cytosis?’

—Devon Chabot-Richards, MD

When a case is evaluated by flow cytometry, it is important to correlate the morphology with the immunophenotype. “Mature B-cell populations are clonal by flow cytometry when light chain restriction or loss of light chain expression is identified, which is the first thing to look for,” Dr. Wilson said.

The second most useful marker to evaluate for mature B-cell neoplasms with small to midsize lymphoid cells is CD5. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder and is CD5 positive. The main differential diagnosis is mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Sometimes the latter resembles CLL, which requires evaluating the rest of the immunophenotype. CLL typically has dimmer CD20 and light chain expression than MCL, and is CD23 positive and FMC7 negative, while MCL is most commonly FMC7 positive and CD23 negative.

“We like CD200 as our new marker,” since CD200 is brightly positive in CLL but not in the majority of MCL cases, she said.

If there is any hint that the morphology or immunophenotype is not characteristic, Dr. Wilson said her laboratory performs FISH for t(11;14)(q13;q32) to identify MCL. “If it is CLL, we do FISH and IGHV mutation testing for prognosis.”

For cases that are CD5 negative, next consider whether CD10 is expressed. “The majority of CD10-positive B-cell neoplasms are follicular lymphoma in circulation. You often see small cleaved cells on peripheral smear review.” Hairy cell leukemia, she cautions, will be CD10 positive in 10 to 20 percent of cases. Hairy cell leukemia cells have more abundant cytoplasm with circumferential cytoplasmic projections, and oval or reniform nuclei. “Whether it is CD10 positive or not, hairy cell leukemias have very bright CD20 expression, which is a clue to perform markers for hairy cell leukemia.”

Cases that are CD5 and CD10 negative require additional testing once hairy cell leukemia is excluded as they could be marginal zone lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, rare splenic lymphomas, or possibly not even lymphoma. More than 90 percent of lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas are MYD88 L265P mutation positive and hairy cell leukemias BRAF V600E mutation positive, both of which can be interrogated in peripheral blood.

Flow cytometry had been performed on the peripheral blood of the 58-year-old patient (“debatable,” Dr. Wilson said of the need for flow, “but the clinician had already sent it”), which revealed a dim lambda-light chain restricted B-cell population that expressed dim CD20, CD5, CD23, and bright CD200, and comprised 32 percent of leukocytes. “While the immunophenotype is that of CLL, the diagnosis depends on the monoclonal B-cell count, which for our woman was 3.5 × 109/L” (WBC 11.0 × 109/L, × 32 percent). This does not meet the threshold of 5 × 109/L required for a diagnosis of CLL, and in the absence of lymphadenopathy, the woman was diagnosed as having a monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL).

Fig. 2

The 2016 revision of the WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms, released in 2017, no longer permits a diagnosis of CLL based on associated cytopenias or disease-related symptoms, Dr. Wilson said. The 2016 WHO guidelines also call for distinguishing between high- and low-count MBL. Low-count MBL (less than 0.5 × 109/L monoclonal B-cells) has little to no risk for progression and does not require follow-up. Since the patient in this case has a high-count MBL (0.5–5.0 × 109/L monoclonal B-cells), she has a one to two percent per year risk of progressing to CLL. “This is considered biologically similar to CLL Rai 0 with an increased risk for infection and secondary cancer, and yearly follow-up by flow cytometric evaluation recommended to monitor for progression,” Dr. Wilson said.

The 2016 WHO guidelines further divided MBL into three types: CLL-type (the majority of MBL cases); atypical CLL-type, CD5 positive (need to exclude MCL); and non-CLL-type, CD5 negative. In patients who are non-CLL-type, CD5 negative, the recommendation is to rule out lymphoma with a CT scan or ultrasound, and perform bone marrow or lymph node evaluation if indicated.

“For CLL, a diagnosis based on peripheral blood findings and flow cytometry is sufficient,” Dr. Wilson said. Bone marrow examination is mainly required if the patient is being assessed for remission or is on a clinical trial. The adverse prognostic factors that need to be looked for, particularly in young patients, are immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) mutations (“About half the patients are nonmutated, which is bad,” she said), CD49d (“easily assessed by flow cytometry”), and del(17p) or TP53 mutation. TP53 is important to detect because those patients are often fludarabine refractory. Next-generation sequencing is identifying additional adverse mutations (i.e. NOTCH, SF3B1) that have therapeutic implications.

“The question for the future is, with so many of our new targeted molecular therapies, what will be the relevance of our current prognostic markers? Stay tuned for that.”

Case No. 2 is that of a 60-year-old woman with a long history of rheumatoid arthritis and recurrent bacterial infections. Her CBC showed mild anemia.“We practice in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which is at high altitude, so our red blood cell parameters are actually a little higher than other places,” Dr. Chabot-Richards said.

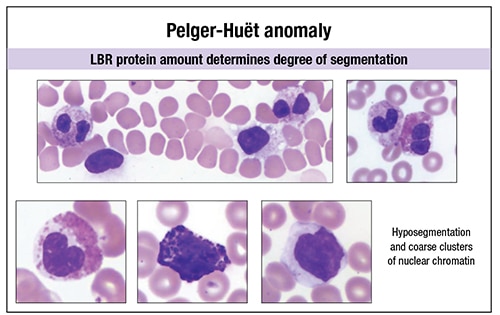

The peripheral blood smear showed that neutrophils were slightly lower than usual, at 22 percent of white blood cells. Her lymphocytes were at 59 percent and appeared mature with nicely condensed chromatin. Monocytes were moderate and not concerning. The edge of the blood smear showed more mature lymphocytes with plenty of cytoplasm, with very granular cytoplasm visible at a higher power.

Fig. 3

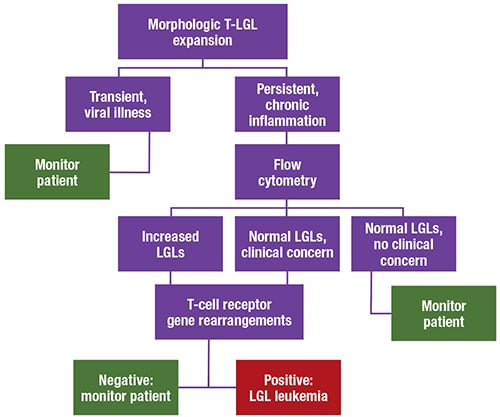

After discussion with the clinician, the case was sent out for flow cytometry. The patient had increased T-cells with co-expression of CD8, CD16, and CD57, with some loss of CD5. The abnormal flow finding and the clinical picture prompted molecular testing for T-cell gene rearrangement, which was positive for a clonal rearrangement. The oncologist further requested that the case be sent out for STAT3 mutation molecular testing, which was also positive.

The patient was diagnosed with T-cell large granulocytic leukemia (T-LGL), a persistent clonal proliferation of T-cell large granular lymphocytes that makes up two to three percent of chronic lymphoproliferative disorders. “It can be difficult to prove clonality in many T-cell disorders,” Dr. Chabot-Richards said.

T-LGL occurs most often in adults ages 45 to 75 and is commonly associated with autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis. The condition is likely due to chronic antigenic stimulation, she said. A benign proliferation of T-cells persists in the body and then develops mutations that lead to a clonal proliferation.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management