Anne Ford

March 2013—When Bobbi S. Pritt, MD, director of clinical parasitology and virology in the Division of Clinical Microbiology at Mayo Clinic, set out to improve test utilization among the physicians for whom her laboratory performs assays, she figured that knowledge was power. Simply educate the clinicians, she thought, and surely they would begin to order the most appropriate tests for their patients.

It took her some time to realize that while knowledge may be powerful, in some situations, it’s just not powerful enough. That is, despite extensive educational efforts, she saw no decrease in order volume for the assay whose utilization she had hoped to reduce—ova-and-parasite testing.

“I don’t think that they [the laboratory’s educational efforts] really did much as far as changing ordering practices,” Dr. Pritt said during “An Algorithm for Detection of Intestinal Parasites: Lessons Learned,” a talk she gave last year at the American Association for Clinical Chemistry annual meeting. “Education is important. It helps establish the laboratory and the laboratorian as a subject-matter expert. It helps get you out of the laboratory, interacting with your clinicians so you can build up that trust … which is essential if you want to start implementing algorithms down the road. But it doesn’t necessarily get you the impact you want.”

In her remarks, Dr. Pritt reviewed the prevalence of parasite-related disease in the United States as well as the most appropriate testing options for it, outlined her laboratory’s efforts to improve utilization of parasitology testing, and supplied recommendations for other labs that might wish to do the same. Her hope: that “some of the principles I’m going to present would be very reproducible in other areas” of the laboratory, not just microbiology.

Dr. Pritt presented the case of a previously healthy four-year-old boy who, along with other children from his preschool class, experienced watery diarrhea of two days’ duration after visiting a petting zoo. She asked her audience to indicate which test they’d choose: stool culture for Strongyloides and hookworm, parasitic examination of stool (ova-and-parasite exam), immunoassay for Giardia and Cryptosporidium, immunoassay for Entamoeba histolytica, or some combination thereof. Seeing a marked lack of consensus among audience members, she said, “I think that this is how the physicians feel … And I think sometimes they just say, ‘Oh, what the heck, let’s just order them all,’ right?”

Actually, she said, the tendency is for physicians to order the ova-and-parasite exam, because it’s “probably our most comprehensive exam as far as being able to detect the number of parasites.” So what’s wrong with that? To start with, “most of the time—I hate to say it—the parasites aren’t even probably the main cause of the patient’s diarrhea,” she said. “It’s probably viral or bacterial, so you’re looking for a needle in a haystack, and … you don’t even have a high pre-test probability that you’re going to find a parasite.”

“But you wouldn’t know that if you just looked at public media,” she added, “because we have all these really interesting television shows now, like ‘Monsters Inside Me’” (a documentary series about parasites). “Physicians and their patients have parasites on the brain, so to speak, and so they want to order tests for parasites.”

Then there’s the fact that the ova-and-parasite test is not the most sensitive option for detecting North America’s two most common intestinal parasites associated with diarrhea: Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Using ova-and-parasite to rule out Giardia as a cause of diarrhea, for example, could require as many as seven stool specimens. “Can you imagine asking your patient to come back in seven times with a stool specimen?” she asked. “Do you know how popular that will not be?” In addition, the ova-and-parasite test is “a subjective morphologic examination,” she noted. “You need well-trained technologists, and they have to be highly experienced.”

Then there’s the fact that the ova-and-parasite test is not the most sensitive option for detecting North America’s two most common intestinal parasites associated with diarrhea: Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Using ova-and-parasite to rule out Giardia as a cause of diarrhea, for example, could require as many as seven stool specimens. “Can you imagine asking your patient to come back in seven times with a stool specimen?” she asked. “Do you know how popular that will not be?” In addition, the ova-and-parasite test is “a subjective morphologic examination,” she noted. “You need well-trained technologists, and they have to be highly experienced.”

All that to say: Unless the patient has lived in or visited an area of the world in which helminths (parasitic worms) are common, an ova-and-parasite test would probably not be indicated. Better options, Dr. Pritt said, are “some special stains [modified acid-fast stain and modified trichrome stain], which are good in certain situations.” There are also antigen detection assays, such as for Giardia and Cryptosporidium and for Entamoeba histolytica, although the latter is not common in North America. “We have some other methods: antibody detection using serum, a stool culture for Strongyloides and hookworm—again, not very common in the United States—and then in some research settings, we have PCR. But when you tell the physician all of this, and you say, ‘These are your options,’ they don’t know which one to order because there’s just so many of them.”

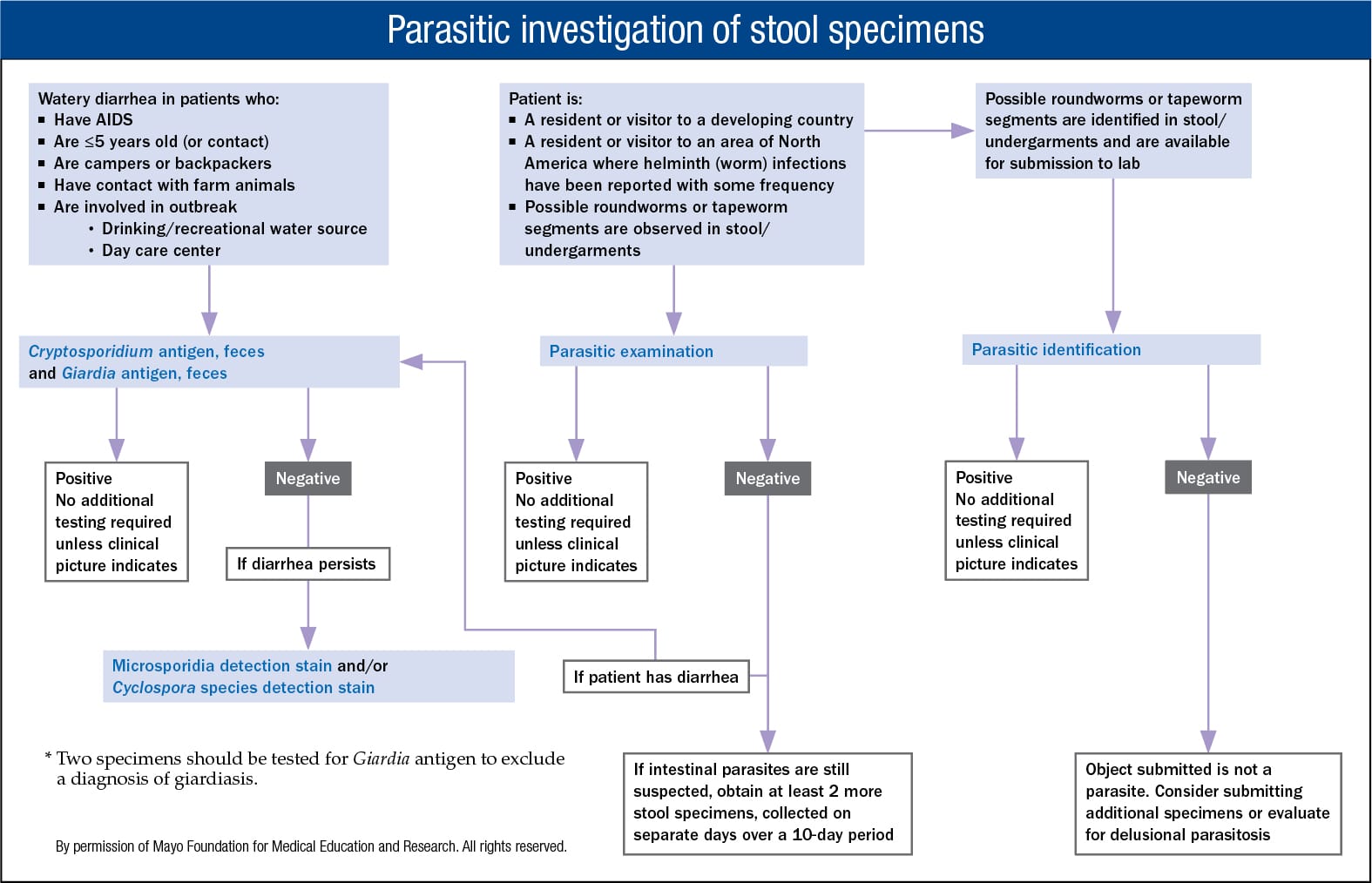

That’s why, she said, the preferred approach would be for physicians to use an algorithm to guide their testing, based on how the patient is presenting and what his or her risk factors are. As she presented the algorithm to the audience, it seemed simple enough: “If you happen to have a patient who has watery diarrhea who has AIDS, had contact with farm animals, or was involved in an outbreak, such as municipal water supply or a day care center, like our patient, you would want to consider ordering the Cryptosporidium antigen.” (Indeed, the patient she mentioned earlier in her talk did test positive for Cryptosporidium.)

That’s why, she said, the preferred approach would be for physicians to use an algorithm to guide their testing, based on how the patient is presenting and what his or her risk factors are. As she presented the algorithm to the audience, it seemed simple enough: “If you happen to have a patient who has watery diarrhea who has AIDS, had contact with farm animals, or was involved in an outbreak, such as municipal water supply or a day care center, like our patient, you would want to consider ordering the Cryptosporidium antigen.” (Indeed, the patient she mentioned earlier in her talk did test positive for Cryptosporidium.)

And if the patient is not yet five years old, or is a camper or backpacker who might have drunk out of a stream, “you’d want to also consider ordering the Giardia antigen.” Given that the risk factors for Cryptosporidium and Giardia infection overlap, “we actually recommend that both antigen tests be ordered together” (see algorithm, left). In contrast, a select group of patients (travelers, immigrants, and people living in small pockets of the United States such as Appalachia) may have been exposed to intestinal parasites such as roundworms. “That’s the main situation where you would want to order that ova-and-parasite exam,” Dr. Pritt says.

Doesn’t sound too difficult. “I should be able to convince all my physicians to do this, right?” she said. “All right, well, unfortunately, there’s some challenges.” First, she pointed out, “the initial selection of tests, and any sequential tests they may decide to do, all depend on clinical factors. And how many of you feel like you really get all those clinical factors you ask for?” Her laboratory used to include a form asking about the patient’s travel history with every stool collection kit, for example, but repeatedly would get unhelpful answers such as “one hour in the car”—when they were filled out at all.

“So the problem you can see here,” Dr. Pritt said, “is that [for the ova-and-parasite exam] the laboratory professionals have little control over ordering decisions. We can’t even go in and cancel tests … or have an algorithm … where a single initial test will allow a cascade to happen.” Usually just one test is ordered, “and we don’t know if it’s appropriate or not, because we don’t know all of the inputs—all of that clinical background,” she said. Instead of the laboratory controlling the algorithm, it’s the clinician who controls the algorithm. “So because of that, if we’re going to get them to use the algorithm, we need clinical acceptance.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management