David Wild

August 2019—In the blood bank, all platelets in bags appear to be the same, whether resting or activated, and because they look the same, they may be used as if they’re equal. But they are not.

Elisabeth Maurer, PhD, and Joel N. Kniep, MD, in a recent CAP TODAY webinar, explained that despite all that is done to keep platelet activation to a minimum, activation rates are still high. “And this means a lot of potential impact on patients,” said Dr. Maurer, clinical associate professor, University of British Columbia, and founder of LightIntegra Technology, Vancouver.

The webinar (www.captodayonline.com) was made possible by a special educational grant from LightIntegra, which makes ThromboLux, a class I device for measuring the quality and quantity of microparticles in blood and blood products.

“I think there’s a big benefit to be had from what I like to call a personalized platelet transfusion,” Dr. Maurer said.

A lot of effort goes into minimizing platelet activation to improve efficacy for hematology/oncology patients, she said. For actively bleeding trauma and surgery patients, activated platelets are potentially preferable because they’re hemostatically more active.

While it is possible to determine which platelets are nonactivated, or resting, based on their “discrete” and recognizable shape, “we can’t have scanning electron micrographs of all our platelets, and what we deal with in the blood bank are bags that usually look very much the same,” Dr. Maurer said. As a result, there’s a notion that they are the same.

A large number of activated platelets are in circulation, she said. A study Dr. Maurer and others conducted at six tertiary care centers in which 13,000 platelet transfusions were tested found 36 percent to be activated despite proper storage. The findings are to be submitted to Transfusion.

Dr. Kniep, assistant medical director of transfusion services, University of Coloraado Hospital, and assistant professor, University of Colorado, and his colleagues have documented some of the impact on patients.

“We have a very busy transfusion service supporting the emergency department, the bone marrow transplant service, and the operating rooms,” Dr. Kniep said, adding that the number of platelet products transfused rose from 486 in July 2017 to 725 by June 2018. The hospital receives about 15 pathogen reduction technology platelets; the remainder are conventional platelets. “We primarily reserve the PRT platelets for our bone marrow transplant patients,” he said. He and his colleagues have found that 33 percent of their platelet stock consists of activated platelets.

They studied platelet activation in 2018 in an analysis of patients with hematologic malignancies. “We had six months of baseline platelet transfusion data, and then we did platelet testing for three months and looked at nonactivated platelet transfusions” in a retrospective review. Patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes received the most platelets during the study.

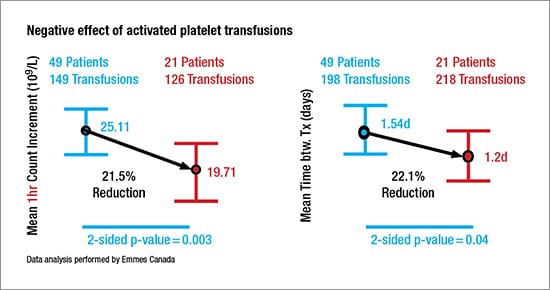

An analysis of data from 149 nonactivated platelet transfusions given to 49 patients, and 126 activated platelet transfusions administered to 21 patients, revealed that activated platelet transfusions were less effective than nonactivated platelets. Mean one-hour platelet count increments declined from 25.11 × 109/L after nonactivated platelets were administered to a mean 19.71 × 109/L after transfusion of activated platelets (P = 0.003) (see “Negative effect of activated platelet transfusions”).

Data from 198 nonactivated platelet transfusions and 218 activated platelet transfusions in the same patient groups found that use of activated platelets shortened the time between transfusions by 22.1 percent, from a mean 1.54 days (37 hours) when nonactivated platelets were administered to a mean 1.2 days (28 hours) after activated platelets were administered (P = 0.04).

Data from 198 nonactivated platelet transfusions and 218 activated platelet transfusions in the same patient groups found that use of activated platelets shortened the time between transfusions by 22.1 percent, from a mean 1.54 days (37 hours) when nonactivated platelets were administered to a mean 1.2 days (28 hours) after activated platelets were administered (P = 0.04).

Dr. Kniep recounted one case, that of a 66-year-old female with AML. The patient was receiving azacitidine and CD33 antibody treatment before undergoing a sibling allogeneic stem cell transplant with fludarabine/melphalan conditioning.

A bone marrow biopsy conducted about one month after the transplant showed full donor chimerism. After the biopsy she was admitted to acute rehabilitation. Following a 10-day stay in rehab, the patient was readmitted to the hospital for worsening diarrhea and was switched from her original regimen of tacrolimus and methotrexate for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis to sirolimus and methylprednisolone.

A subsequent bone marrow biopsy showed hypocellular marrow without evidence of relapsed leukemia. Due to ongoing cytopenias, the patient was started on eltrombopag about two weeks later. It was several days after that that she received the first of 14 platelet transfusions administered over a three-month period.

Using LightIntegra’s ThromboLux to screen for activation status, Dr. Kniep’s team found that the ninth transfusion met the definition of activated platelets, which, according to the manufacturer, is defined as a microparticle concentration greater than 15 percent.

A review of the patient’s outcomes showed that, prior to the ninth platelet transfusion, the average time between transfusions was slightly more than 63 hours. That interval narrowed following transfusion of the activated platelets, dropping to an average of 47 hours between the remaining transfusions, Dr. Kniep said.

In addition, prior to transfusion of the activated platelets, the average platelet count increment was slightly above 60 × 109/L, but it fell to 41 × 109/L after transfusion of the activated platelets.

“One of the questions you may have is, Is there anything that might have happened during that time period either before or around the activated platelet [transfusion] that might confound or possibly could have contributed to the poorer platelet recovery?” Dr. Kniep said.

Dr. Kniep

At about the time of the activated platelet transfusion, the patient had an episode of hypertension and became unresponsive, requiring resuscitation with albumin and intravenous fluids. “She responded to treatment but then became unresponsive again,” Dr. Kniep said.

A stroke was called and she was transferred to the hospital’s ICU where she was intubated and arterial and central lines were placed. Blood cultures revealed Gram-negative rods, and the patient was given additional antibiotics. Chest x-ray revealed bilateral pleural effusions. The patient was placed on stress-dose steroids.

“Overall,” Dr. Kniep said of his group’s study, “we found there was a decrease in count increment and time between transfusion. Clinically that can translate into additional platelet transfusions for the patient. And that’s additional money out of the blood bank budget in a time when we are constantly being asked to do more with less and to try to minimize transfusions throughout the hospital.”

Dr. Maurer describes the Thrombo-Lux device as a “small benchtop instrument that is easy to use and can, in a very small, almost toothpick-sized, sample from a platelet concentrate or a platelet-rich plasma, characterize the platelets in that sample.” It detects platelet activation by the fragments of cells, called microparticles. CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management