Valerie Neff Newitt

January 2020—When looking at a liver biopsy, always suspect there might be drug-induced liver injury. “But then try hard to prove there isn’t. It’s always a diagnosis of exclusion and pattern evaluation,” says David E. Kleiner, MD, PhD, reference pathologist for the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network. In that role, he pieces together clues that point to a drug having injured a liver—or not.

Drug-induced liver injury is rare, and few pathologists see it. “The incidence is between one in 100,000 and one in a million, depending on what survey you read,” Dr. Kleiner says.

His advice: “Think of all the other things it could possibly be and rule those out before you say, yes, this is drug-induced liver injury. If it sounds like a big job, well, yes, it is. It’s probably the most challenging area in liver pathology.”

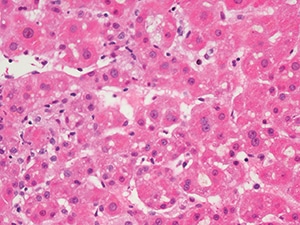

Mild parenchymal inflammation and cholestasis from a young man with anabolic-steroid-induced jaundice (H&E, 400×). Images courtesy of David Kleiner, MD, PhD.

The Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network, or DILIN, was created in 2003 by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. It was in part “the result of a head-turning 2002 article [Lasser K, et al. JAMA. 287(17):2215–2220] that cited liver toxicity as the most common cause of a drug being withdrawn from the market or black boxed,” says Dr. Kleiner, who is a senior research physician in the Laboratory of Pathology at the National Cancer Institute, where he is also chief of the postmortem pathology section. “After that paper, there was a lot of attention by the FDA and Liver Diseases Research Branch of the NIDDK to see if they could explore this issue more.”

DILIN consists of one data coordinating center, at Duke University, and hepatologists working at a half-dozen clinical sites. There are prospective and retrospective studies; Dr. Kleiner works on the prospective side. “Patients suspected of having drug-induced liver injury and meeting certain criteria can be enrolled in the network’s study. They’re followed for up to two years with periodic evaluations. Clinicians collect biosamples, blood, DNA. And then when there is a liver biopsy—and if they can get re-cuts of the biopsy—it is sent, under code, to me.”

All of the drugs the network concerns itself with are considered to cause injuries that are idiosyncratic in nature. “These drugs are generally thought to be one-offs,” Dr. Kleiner says. “Even if patients have susceptibility to these, they may not develop injury. The incidence varies between about one in a thousand to one in a million patients taking the drugs. Because it’s such a low number, usually these drugs are not caught as potential problems during clinical trials.”

‘Drugs cause a lot of different patterns as a whole, but every individual drug might only cause two or three.’ — David Kleiner, MD, PhD

In contrast, some drugs are considered to be intrinsic dose-related hepatotoxins causing direct injury. “If you give the drug and keep ramping up the dose, you will destroy the liver,” Dr. Kleiner says. “Unfortunately, acetaminophen is probably the best example of that.” Antibiotics, too, show up in surveys of DILI as causes. “One reason is that antituberculous medications, particularly isoniazid, are problematic.” Others, like Augmentin, have an HLA association, he says. “But possibly only one in 600 of those patients who have that HLA allele is at risk for or develops injury. So it’s not reasonable for patients to get tested, have HLA determined, and then avoid those drugs.” Many are common drugs, though the injury is still uncommon. “Patients could unnecessarily avoid good drugs they really need,” he says.

A third group of injury is related to idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity. “This generally refers to hepatotoxicity that requires some processing of the drug to a reactive metabolite, as compared to direct hepatotoxins, which are basically poisons,” Dr. Kleiner says.

As new drugs enter the marketplace, other areas of possible hepatotoxicity are emerging. “Checkpoint inhibitors form a distinct group as their hepatotoxicity relates to their mechanism of action,” Dr. Kleiner explains. “They work by de-inhibiting the immune system so it can fight the cancer but increase the risk of autoimmune-like injury. The toxicity is therefore frequently referred to as immune-related.”

Also to be considered are tyrosine kinase inhibitors. “At least some of them can cause significant injury. Imatinib is a classic example,” he says. “The problem we face is that such drugs are being approved very quickly and there is insufficient data on the risk they pose to the liver, yet based on structure or function, some of the new drugs may have significant potential for toxicity.”

Since DILIN began, more than 2,000 patients have been enrolled in the prospective study, and about 800 biopsies have been sent to Dr. Kleiner.“In the beginning, I know nothing about the patients in the study,” he says. “I meet them mainly as unstained slides. I stain them, using standard stains, and do an evaluation, looking for different features. I classify the pattern into a number of different patterns seen in drug-induced liver injury—like acute hepatitis, granulomatous hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, or nodular regenerative hyperplasia.” He has defined about 18 patterns. “I’ve also created a structured evaluation method to look at the biopsies, grade the various features, and record them in a way that could be put into a database.”

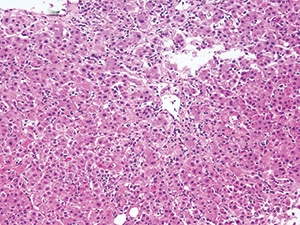

Moderate acute hepatitis with numerous foci of lobular inflammation and scattered apoptotic hepatocytes in a case of acute liver injury from a green-tea-containing weight-loss product (H&E, 200×).

When Dr. Kleiner evaluates slides, he does not make a determination about whether there is drug-induced liver injury. Rather, he categorizes the patterns he sees. “A few drugs have very characteristic histologic changes. Amiodarone, for instance, has a distinctive injury pattern, and so even if you don’t know anything about the case, sometimes you can recognize that. But for the most part, that’s not true. To understand whether a biopsy is showing liver injury usually requires careful correlation of the clinical history with the histology.”

“The hepatologists have a form they follow to look at the details of the case, the history, the laboratory data, et cetera, and then they decide whether they believe there was drug-induced liver injury, and which drug the patient was taking that may have caused it.”

Dr. Kleiner’s evaluations and the hepatologists’ reviews all come together in papers. “A number of projects have come out of this network and the data we’ve produced. We’ve written what could be considered classic clinical pathologic correlation papers,” Dr. Kleiner says, citing as an example a 2014 article in Hepatology (59[2]:661–670). “For instance, on the statins or the cephalosporins, we’ve summarized the clinical presentation, the laboratory data, the histology, and any other information we think might be useful and published those case series.”

In another DILIN project, a subgroup of clinicians is going back and reexamining cases. “We’ve taken out all of the information that came after the liver biopsy was performed. The clinicians might have five days of labs and history to review. We’re asking them to decide, based on that initial information, if they suspect there’s drug-induced injury and whether or not they would do a liver biopsy.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management