Anne Paxton

March 2020—While developing into a global health emergency that has killed thousands, the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus identified in China riveted the public and raised awareness of infectious diseases and their perils.

But despite its ability to empty city streets in China and devastate communities, from a medical standpoint SARS-CoV-2 has an advantage. It rapidly gained worldwide attention, spurring the development of rapid diagnostic methods and potential treatment modalities. In contrast, the yeast Candida auris, a different emerging species of pathogen that is well below the public’s radar, has not only the potential for severe harm and a pattern of spreading easily in the hospital, but also the danger of being difficult to identify and treat.

C. auris, first isolated in 2009, does not pose anywhere near the hazard that SARS-CoV-2 does, but the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that C. auris presents a serious global health threat. Candida is one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections and C. auris presents unique challenges, says Romney Humphries, PhD, D(ABMM), chief scientific officer, Accelerate Diagnostics, Tucson, Ariz., and a member of the CAP Microbiology Committee. “If we don’t keep an eye on it, it does have the possibility to expand very rapidly and be very problematic for some of our sickest patients,” she warns. A new article by Dr. Humphries, D. Jane Hata, PhD, D(ABMM), and Shawn Lockhart, PhD, D(ABMM), in Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine details the distinct challenges that C. auris poses for laboratory diagnostics and for infection prevention and treatment (2020;144[1]:107–114).

C. auris is the first yeast to cause an infection that is both multidrug resistant and frequently misidentified by the forms of testing available in most clinical microbiology laboratories. “If you don’t have a good identification method, you don’t really know what your prevalence is,” says Dr. Hata, director of microbiology at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and a former member of the CAP Microbiology Committee. However, with C. auris having become a nationally reportable condition in 2018, the information on its prevalence will likely improve in the years ahead.

Dr. Humphries

“From a global public health perspective,” Dr. Humphries says, “people are worried about C. auris because it has such a propensity to mutate and become resistant to all the different classes of antifungal.” About 40 percent of C. auris isolates will be resistant to two or more drug classes, and 10 percent will be resistant to all antifungal drugs. C. auris is not more pathogenic than other drug-resistant pathogens, she adds, but it is associated with health care exposure, and “the type of patients who typically become infected with C. auris are already very sick.”

“There’s a real desire to be able to identify this and understand the epidemiology and track it,” she says, “just as we do with multidrug resistant bacteria.” Accurate laboratory identification is a key part of that. Preventing the spread of C. auris in the hospital can be accomplished through infection control activities, Dr. Humphries says, “but that can only be done if you know who has the infection.”

While it is still rare in the U.S.—as of June 2019, 725 confirmed and 30 probable cases of C. auris infection had been reported, mostly in hospitals and nursing homes in New York City, New Jersey, and Chicago—multiple strains of C. auris called clades have emerged independently in various parts of the world since the species was first identified. It is unprecedented to observe the simultaneous rapid worldwide emergence of a newly identified Candida species, Drs. Humphries and Hata say.

“This is an extremely interesting organism because prior to 2009, it had never been reported,” Dr. Hata says. “One of the valuable things when we investigated the emergence of C. auris was that we had large collections of Candida isolates from all over the world going back to 2001. We looked at those older isolates using various genomic methods to see if we could detect it, and no strains of C. auris were detected in these large culture collections before 2009. So this speaks to the fact that we have a newly emerging Candida species.”

It’s an emergence that has undermined two long-standing assumptions about Candida infections: that standard infection control practices can ward off outbreaks and that Candida can be effectively treated because most Candida isolates are susceptible to available antifungal agents. C. auris is resistant to agents commonly used to treat Candida infection such as fluconazole. “We also see resistance, in some cases, to our echinocandins like caspofungin which target the fungal cell wall, as well as our drug of last defense: amphotericin B. And C. auris seems to be developing more resistance the more we see of it, which is a huge concern,” Dr. Hata adds.

Dr. Hata

“C. auris is also very unusual in exhibiting environmental persistence. These yeast can survive on a dry surface for seven to 14 days and be recovered and become viable again. Some studies have reported they can be environmentally resistant but recoverable after one month, which is extremely unusual for any yeast species. So C. auris presents special issues when it comes to decontamination of surfaces and cleaning of patient rooms, as well as handling in the laboratory.”

Adding to the complications, people may become colonized with C. auris on their skin but not exhibit symptoms of disease, and accurate identification of colonizing organisms can be a challenge for the laboratory, Dr. Hata says. And although the CDC currently recommends that health care facilities place patients with C. auris colonization or infection in single rooms, “there’s a big infection control problem because patients aren’t ill, so they may not be placed under the appropriate isolation precautions to prevent C. auris from spreading throughout a hospital unit.”

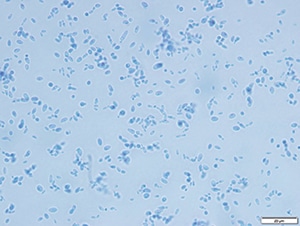

As explained in the Archives article, C. auris cannot be identified by morphology alone, and commercially available phenotypic methods fall short in accurately identifying it. Automated and nonautomated biochemical methods have performance issues, and overlapping biochemical profiles and limitations in identification databases can cause a low confidence result, misidentification as another Candida species such as C. sake or C. famata, or genus-level identification (Candida species) only.

Lactophenol cotton blue slide preparation of C. auris, 40× magnification.

(Courtesy: Diana M. Meza Villegas, MS, SM(ASCP)CM, and Miranda E. Diaz, BS, SM(ASCP)CM, Mayo Clinic Florida microbiology laboratory.)

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management