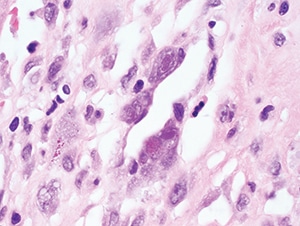

Figure 4.30. Characteristic nuclear Cowdry type A and cytoplasmic inclusions within endothelial cells in this case of myocarditis

(H&E, 1000X).

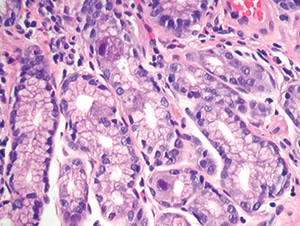

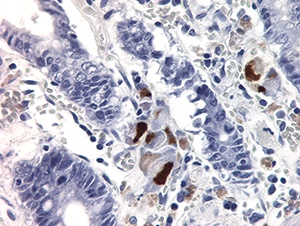

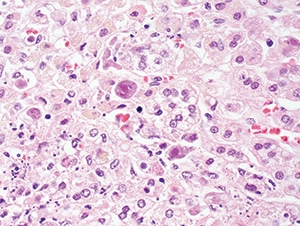

Pathologic features. Tissue samples are rarely taken in immunocompetent hosts with self-limited disease but may be performed for other reasons and will often demonstrate classic CMV viral cytopathic changes: cytomegaly (up to four times larger than uninfected cells), a large single basophilic to amphophilic Cowdry type A intranuclear inclusion (“owl’s eye”), and multiple dense, eosinophilic to basophilic cytoplasmic inclusions (Figs. 4.30 and 4.31). Cytoplasmic inclusions (but not nuclear inclusions) may be weakly positive with Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). In immunocompromised patients, the viral cytopathic effect is similar but may be more frequent and associated with necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates (Fig. 4.33). The type of cells with viral cytopathic change varies with the affected organ; in the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and lung, CMV may involve both epithelial and endothelial cells. Alveolar macrophages in the lung may also be infected. Pneumonitis can result in nonspecific diffuse alveolar damage without necrosis for which careful examination is needed to find cells with characteristic viral cytopathic effect (Figs. 4.28 and 4.29). In the brain, neurons may contain characteristic inclusions. Retinitis in both congenital infection and HIV-related disease typically demonstrates retinal necrosis, vasculitis, and choroiditis. Immunohistochemical stains or ISH for CMV are helpful for demonstrating infected cells and may also highlight cells without obvious viral cytopathic effect (Fig. 4.32). Since incidental reactivation of CMV may be detected in immunocompromised patients with other infectious and noninfectious conditions, positive IHC or ISH staining must be carefully correlated with the clinical picture.

Figure 4.31. Intestinal biopsy shows two epithelial cells with clear cytomegalovirus viral cytopathic effect. Note the lack of associated inflammation (H&E, 200X).

Differential diagnosis. CMV inclusions must be differentiated from other viral inclusions including those of HSV, VZV, adenovirus, BKV, and JCV. Use of virus-specific IHC or ISH stains and correlation with culture and PCR results are helpful for confirming the diagnosis. Other infectious and noninfectious entities such as graft-versus-host disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients can cause similar necrotic/inflammatory lesions and should be considered.

Figure 4.32. Multiple epithelial cells stained positively with cytomegalovirus IHC in a patient with severe gastroenteritis. Endothelial cells (not shown) were also highlighted (400X).

Ancillary tests. Qualitative PCR or culture can be performed on a variety of specimens and may be used to support the diagnosis of active infection. Quantitative CMV PCR is used primarily in immunocompromised individuals to assess risk of disease and monitor response to therapy. However, quantitative PCR results must be carefully interpreted since several studies have shown a clear disconnect between severe organ involvement and a lack of peripheral viremia and vice versa. Serologic assessment is useful for diagnosis of primary infection, especially in pregnant women and patients with a mononucleosis-like illness. It is also useful for risk stratification of transplant recipients and donors.

[hr]

Figure 4.33. Cytomegalovirus adrenitis in a patient with AIDS, showing enlarged cells with intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions (H&E, 200X).

Clark NM, Lynch JP 3rd, Sayah D, Belperio JA, Fishbein MC, Weigt SS. DNA viral infections complicating lung transplantation. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34(3):380–404.

Fishman JA. Overview: cytomegalovirus and the herpesviruses in transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 3):1–8.

Karre T. Herpes virus infections. In: Procop GW, Pritt BS, eds. Pathology of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:17–36.

Kotton CN. CMV: prevention, diagnosis and therapy. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 3):24–40.

Pillet S, Roblin X, Cornillon J, Mariat C, Pozzetto B. Quantification of cytomegalovirus viral load. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(2):193–210.

Razonable RR, Hayden RT. Clinical utility of viral load in management of cytomegalovirus infection after solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(4):703–727.

Söderberg-Nauclér C. Treatment of cytomegalovirus infections beyond acute disease to improve human health. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(2):211–222.

von Ranke FM, Zanetti G, Hochhegger B, Marchiori E. Infectious diseases causing diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in immunocompetent patients: a state-of-the-art review. Lung. 2013;191(1):9–18.

You DM, Johnson MD. Cytomegalovirus infection and the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14(4):334–342.[hr]

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management