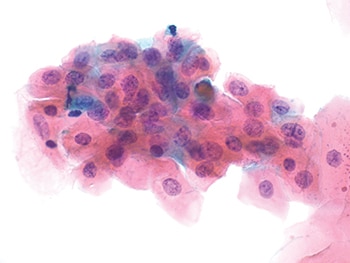

Fig. 3. One cluster of LSIL cells (600×) with nuclear enlargement and eosinophilic cytoplasm and no perinuclear cavitation.

In 2001, the initial ASCCP and ACOG consensus guidelines recommended immediate colposcopy for all non-adolescent premenopausal women with LSIL, regardless of HPV results. These recommendations were facilitated by the consensus that there was little utility for routine reflex HPV testing in managing LSIL Pap test results, given the high percentage of LSIL cases found to be hrHPV-positive. However, subsequent publication of the ALTS data confirmed that five to 16 percent of women with LSIL Pap results tested hrHPV-negative.10 Recent data have further demonstrated that the risk for histopathologic CIN2+ and CIN3+ for women with hrHPV-negative LSIL results may be as low as three percent and 0.2 percent, respectively, significantly less than the risk for patients with hrHPV-positive LSIL and similar to the risk for patients with ASC-US alone.11

Several explanations for the presence of hrHPV-negative LSIL have been put forward, including non-oncogenic HPV infections, cut-point–related sensitivity limitations implemented to enhance specificity of hrHPV tests, false-positive Pap test results, and viral clearance before the time of histologic sampling.6,10 These findings have led to the concept that women with hrHPV-negative LSIL co-testing results might be better managed less aggressively. As a result, the most recent cervical screening test management guidelines, released in 2012, recommend that the preferred follow-up method for women with hrHPV-negative LSILs is to repeat cytology and hrHPV co-testing at one year, deferring immediate elective colposcopy.12

Women with hrHPV-negative LSIL are not the only subgroup of LSIL with an alternative management strategy in which immediate colposcopy may be deferred. Young women under age 25 have a low risk of progression to cervical cancer owing to their high clearance rate of HPV infection and high regression rates of cervical disease. Therefore, young women with LSIL, both pregnant and nonpregnant, are initially managed with repeat cytology at 12 months. Colposcopy is deferred unless ASC-H+ or ASC-US+ is detected at 12 and 24 months follow-up, respectively. The preferred management of non-adolescent pregnant women is colposcopy; however, it is acceptable to defer colposcopic examination until at least six weeks postpartum due to the high rate of postpartum regression of cervical disease and the low rate of cervical cancer. Similarly, postmenopausal women with LSIL are managed optimally with hrHPV testing, repeat cytologic testing at six months and 12 months, followed by colposcopy if ASC-US+ is detected or if they test hrHPV-positive.

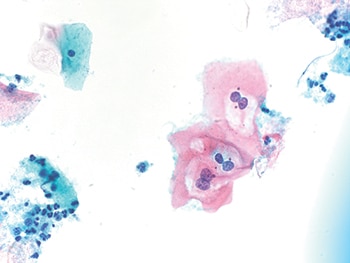

Fig. 4. One small cluster of LSIL cells (600×) with perinuclear cavitation, binucleation, and slightly enlarged nuclei.

The enhancement of cervical screening with hrHPV co-testing and installation of longer screening intervals has made it possible to accumulate new data on LSIL including age-based risk stratification of disease progression with regard to hrHPV infection. These data have supplemented the initial findings of the ALTS trial, leading to modification of management guidelines. In addition, new cytologic categories, such as LSIL-H, have been identified that impart increased risk of cervical disease to patients but lack clinical management guidance. As the examination of the relationship between hrHPV and cervical disease continues and new data accumulate, there may be a shift from the dependence on a broad consensus guideline to a more personalized approach to management.

- Solomon D, Davey D, Kurman R, et al; Forum Group Members; Bethesda 2001 Workshop. The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2114–2119.

- Eversole GM, Moriarty AT, Schwartz MR, et al. Practices of participants in the College of American Pathologists interlaboratory comparison program in cervicovaginal cytology, 2006. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(3):331–335.

- Arbyn M, Martin-Hirsch P, Buntinx F, Van Ranst M, Paraskevaidis E, Dillner J. Triage of women with equivocal or low-grade cervical cytology results: a meta-analysis of the HPV test positivity rate. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(4):648–659.

- Arbyn M, Sasieni P, Meijer CJ, et al. Chapter 9: Clinical applications of HPV testing: a summary of meta-analyses. Vaccine. 2006;24(suppl 3):S78–S89.

- The Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance/Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Human papillomavirus testing for triage of women with cytologic evidence of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: baseline data from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(5):397–402.

- Heider A, Austin RM, Zhao C. HPV test results stratify risk for histopathologic follow-up findings of high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia in women with low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesion Pap results. Acta Cytol. 2011;55(1):48–53.

- Barron S, Li Z, Austin RM, Zhao C. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL-H) is a unique category of cytologic abnormality associated with distinctive HPV and histopathologic CIN 2+ detection rates. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141(2):239–246.

- Dunn TS, Burke M, Shwayder J. A ‘‘see and treat’’ management for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion Pap smears. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2003;7(2):104–106.

- Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, et al. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV-positive and HPV-negative high-grade Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S50–S55.

- Zuna RE, Wang SS, Rosenthal DL, et al. Determinants of human papillomavirus-negative, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in the atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions triage study (ALTS). Cancer Cytopathol. 2005;105(5):253–262.

- Barron S, Austin RM, Li Z, Zhao C. Follow-up outcomes in a large cohort of patients with HPV-negative LSIL cervical screening test results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143:(4)485–491.

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):829–846.

Dr. Barron Miller is an assistant professor of pathology, Department of Pathology, Allegheny General Hospital, Pittsburgh, and Dr. Zhao is a professor of pathology, co-director of cytopathology, and director of FNA Service, Department of Pathology, Magee-Womens Hospital, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Zhao is a member of the CAP Cytopathology Committee.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management