Illumina TruSight™ Oncology 500 automation methods & automation kits available now. Enable CGP with flexibility and scalability in-house. Learn more.

TELCOR RCM helped this business in a number of ways. Since being live they saw a 33% staff reduction with no need to replace those FTE’s. Learn more.

CAP TODAY Roundtable

How close to patients? Cost, quality, competition

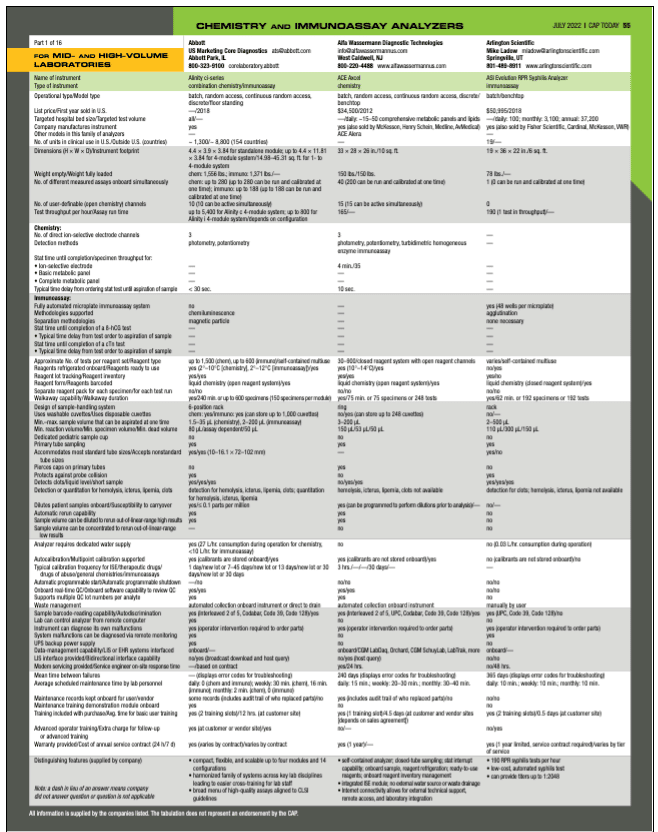

July 2022—Point-of-care versus centralized testing, and automation, IT, and staffing. It all came together as industry executives and a laboratory director and a former medical director met with CAP TODAY publisher Bob McGonnagle on May 25, as CAP TODAY’s list of chemistry and immunoassay analyzers was going together (see product guide).

“I don’t worry much about the machines or reagents,” thanks to good-quality practices, said André Valcour, PhD, MBA, DABCC, of Labcorp, who noted the real focus is quality of information and information transfer.

Susan Fuhrman, MD, formerly of OhioHealth, said, “We should always give our clinicians as much information as we can accurately produce and our reports should be as clear as we can make them.” And of the staffing crisis: “We have a perfect storm,” she said.

Here is more of what they and the others had to say.

Dr. Fuhrman

I’d like to talk about what we’ll call the testing architecture for large health care systems. Patient demands and preferences are beginning to play an ever-bigger role in how we strategically architect these testing systems. Susan Fuhrman, can you comment on that?

Susan Fuhrman, MD, former president, CORPath, and former system medical director, Department of Pathology and Laboratories, OhioHealth and Riverside Methodist Hospital: Health systems are competing for patients across different service lines, and outpatient market share is incredibly important to them. Patients love one-stop shopping. In affluent areas patients shop around for convenience, which they can readily assess. In less affluent areas there are issues with patients failing to follow up with providers after labs are abnormal. Having testing available where the patients are is an obvious solution to nonlaboratorians.

Laboratories have been resistant to the added expense for patient convenience. My tack when talking with administrators and clinicians and trying to find a solution is to lay out the increased costs and clinical pros and cons and let them run their numbers and decide whether it’s worth the price to gain market share. It’s a matter of the system believing it’s worth the extra cost to bring testing nearer to the patient and to duplicate testing in multiple sites.

André Valcour, what’s your perspective on this?

André Valcour, PhD, MBA, DABCC, vice president and laboratory director, Center for Esoteric Testing, and discipline director of allergy, coagulation (core lab), and endocrinology, Labcorp: I come from the perspective of centralization. The cost of logistics associated with centralization may be higher, but in general costs are going to be higher by decentralizing.

We have highly advanced interfaces in automated chemistry with regard to the way we do quality control. We use patient-moving medians very effectively. We believe, and our data show, it’s more capable of catching small changes in instrument performance well before you catch it through failures of traditional quality control. It’s a much more real-time capture of changes in instrument performance.

Decentralization makes sense when you can make important clinical decisions more rapidly. It’s worth the expense to the extent it’s needed for optimal patient care. And the patients like to get their results quicker.

From a health economics perspective, centralization, in cases where you can provide the same level of patient care, will be less expensive. Decentralization means you ensure you have the same level of quality in many sites. If you do it in a large reference laboratory using the most advanced interfaces and quality systems, you can control quality better.

Medaugh

Brooke Medaugh, as a representative of a point-of-care chemistry approach, does this ring true in terms of what your customers are facing in trying to be effective with their testing strategies?

Brooke Medaugh, product manager, chemistry, Horiba Medical: Yes. We see both sides. For small labs it can be cost-effective to run routine testing in a physician office laboratory, but it may be less cost-effective for them to run low-volume esoteric tests. Sending out to a centralized testing facility for these types of tests can be more cost-effective as they have the resourcing to combine test volumes from many sites. However, we see a clinical need for having near-patient testing as an option, particularly for rural and critical access health care facilities.

Ed Bass, we talk about the point of care, the need for core lab automation, but there’s no one-size-fits-all equation for figuring that out within a system, is there?

Edward Bass, MBA, marketing manager, systems, Werfen: I agree; there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. However, autoimmunity is a specialized disease state, so we’re more associated with hospital laboratories. Autoimmunity testing is considered a specialty island within the laboratory. However, we do have a smaller instrument, Bio-Flash, that is being used by the larger rheumatology practices that have a laboratory.

We also provide a data-management system, Quanta Link, to facilitate decision-making. Many general practitioners and family practice physicians will order an antinuclear antibody test as the first line of screening. If it is positive, in most cases they refer the patient to a specialist, who manages the patient moving forward. At this time, autoimmunity testing is not performed at the point of care.

Shannon Garegnani, does this ring true as you look at systems and customers who are looking to optimize the testing architecture?

Shannon Garegnani, marketing manager, chemistry and immunoassay, Beckman Coulter: Health economics is a huge topic for us and as we work with our large network customers. We’re working with customers who are asking how to centralize certain testing to keep things cost-effective while also balancing the need for testing close to patients. Complete centralization is not an option for all systems, so they still have to have ancillary labs or point-of-care services.

From a chemistry and immunoassay perspective, we focus on having our complete menu available no matter the size of instrumentation so labs can come up with a plan to best meet their needs. If there are specialty labs that do not have high volume, they don’t have to purchase the largest equipment we have. You can see that throughout our business strategy.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, which is part of the reason we have a team dedicated to consulting with and developing plans for health networks to come up with what will work for them. In some cases, we can go into a guaranteed outcomes model to ensure they’re performing the way they want.

Tell us a little more about the guaranteed outcomes model.

Shannon Garegnani (Beckman Coulter): Beckman Coulter has a team called Performance Partnership. At the service level it’s a program that takes a holistic view of a network’s process, people, and technology to optimize equipment use, resize resources to meet demand throughout the network, and find excess capacity to maximize patient care. Overall, Beckman Coulter has a deep understanding of the lab since it is our primary focus. We are able to not only provide recommendations for optimization but we put our skin in the game to drive measurable results by sharing the financial risk. Our current partners see tremendous value in the program so we have been able to expand the number of health networks we provide this service to.

Susan, OhioHealth is a member of the Compass Group, which represents large integrated delivery networks. If you add them all together, they are as large as Quest or Labcorp in terms of total test volumes and revenues. Do you see these large networks continuing to grow?

Dr. Fuhrman (formerly OhioHealth): Absolutely. What I’ve found interesting about the Compass Group was the marriage that was developing between academic medical centers and private hospitals. These mixed networks, which have a very different flavor to them, have an advantage because they can do esoteric testing, they have the expertise for near-patient testing, and they have generalist pathologists and specialist pathologists. That model is very attractive.

I want to respond to the question you asked Ed, because I am familiar with those assays. I agree with Ed; I wouldn’t be doing those tests at a small lab or at the point of care. They require expertise to set up and expert technologists to run. It’s testing that’s best left to the experts. We as laboratorians want to provide the best quality we can, and the tradeoff we’re discussing, even between centralized and decentralized, is, What’s reasonable? What provides the best care for our patients all around? That’s why it takes more than laboratories to be making the choices.

Ed, I’m sure you’re not detailing the Marcus Welbys of this world at Inova.

Edward Bass (Werfen): That is correct. Our level of testing involves a higher level of technologist expertise to interpret results and a specialist, specifically a rheumatologist, who makes the follow-up decisions.

That said, we strive to build our instruments to meet all needs, not only decentralized with efficient workflows but instruments that provide workflow efficiencies for a technical type of testing, such as indirect immunofluorescence assay, which requires a higher level of expert interpretation.

Brooke, how are you at Horiba responding to the shortage of health care workers generally, not just technologists but nurses and others?

Brooke Medaugh (Horiba): We design our products to be used by as many different types of technologists as possible. We make everything user-friendly, and we’re expanding our menu of moderately complex tests. We recently added toxicology drugs-of-abuse testing to our Pentra C400 benchtop system’s extensive chemistry menu. If you’re in a clinic where you may not have a highly experienced medical laboratory scientist running the testing, you can still have a broad menu.

André, the Compass Group, a group of not-for-profit integrated delivery network system lab leaders, arose in part because large, for-profit national labs have advantages with labor and with payers. Do you see a parallel rise between large IDNs and systems and the development of Labcorp, Quest, and Sonic, to name three?

Dr. Valcour (Labcorp): If there is an optimal solution, there’s one optimal solution. The success of the larger reference laboratories is a model that makes sense for consortiums to emulate.

I’d like to talk about the labor issue. In allied health, it’s unfortunate that medical technologists get short shrift, generally. For what they do and how they impact health care—it’s been estimated 70 percent of medical decisions are made based on laboratory testing—they haven’t achieved the same stature financially as nurses or as other allied health workers. It’s unfortunate because they have so much impact on the health care system.

That being the reality, we have to build intelligent systems to make it easier for laboratories to prevent error and ensure accurate and quality results. Large reference labs and consortiums have an advantage because they can make the investment to build intelligent middleware and robust autoverification and partner with diagnostic companies like Werfen and Beckman Coulter to build intelligent hardware and instrument systems.

One other thing we can do is write programs for clinical decision support and interpretive reporting to allow clinicians to not only get a good result but also a result they can use. The smaller you are, the harder it is to make those investments in infrastructure—to have great autoverification, middleware, clinical decision support, so you can live in a world where there are fewer qualified technologists to do the job.

Is there a point at which the solutions of software and automation run up against the problem almost in an asymptotic way? In other words, we have to have enough intelligent bodies running these systems. Or do you believe, Shannon, that companies like Beckman Coulter and people devoted to Lean, like consortiums and large national labs, still have a good way to go to improve on the labor crisis through their offering?

Shannon Garegnani (Beckman Coulter): In the way it exists now, there is no automation or informatics system that can effectively replace all the technologists who are running the tests. We can automate many of the manual processes, but there’s still a need for technologists to interpret the results and use the knowledge and wisdom they gain by working in the lab to solve problems. We can use intricate technologies to detect errors sooner, but there still needs to be a technologist to see there’s a problem and determine what the solution might be or get the assistance needed to fix it. A lab assistant might say, “There’s an error.” But they don’t have the level of knowledge to dig into, “What does this trend mean? How can I fix it and ensure the quality of results is still great?” So we’re not trying to eliminate the need for technologists. There is a crisis within the industry.

Beckman Coulter’s focus with the DxA 5000 and Remisol Advance solutions are to bridge the gap as best we can between people who do not have the expertise and those few people who are left who have that tribal knowledge and wisdom. We’re able to support that with our sophisticated middleware solutions, Remisol Advance and DxOne Workflow Manager, that allow for intelligent rule writing and alerts. We can take the knowledge and wisdom of your best techs and translate that to software rules.

Surveys done by the American Society for Clinical Pathology and others say the cohort is aging. Ed, do you have thoughts about solutions?

Edward Bass (Werfen): In our area we’ve automated many of the more demanding manual tasks. For example, the indirect immunofluorescence assay. We’ve taken it from the dark room, having a medical technologist using a microscope to interpret images, to putting it on a digital platform so the technologist is looking at digital images. Using our Nova View platform, you’re looking at an image to confirm the instrument’s interpretation.

Our newest instrument, Aptiva, is a multianalyte platform. It is able to process multiple analytes simultaneously using a very small sample aliquot. The instrument generates results only for the analytes ordered. However, if a physician desires to view a result that was not previously ordered the first time, the instrument has a reflex capability to generate follow-up results without the need to reprocess that particular sample. We’re shifting the laborious workflow to our instruments.

Another factor is using precision medicine. That is the future, to create algorithms that deliver information to clinicians to make the proper diagnosis using data we’ve already generated.

Susan, everyone seems to be trying to open a school to supply their own system staffing needs. But is something more needed at the moment to address this shortage? Are we going to have a fall where we might be in a position where some systems might not be able to offer certain testing because of labor shortages?

Dr. Fuhrman (formerly OhioHealth): We’re not doing enough, and we didn’t do it soon enough. We have a perfect storm. We talked about salaries and that technologists are the unsung heroes. Pathology is not as good as we could be about telling our story, and technologists are symptomatic of that as well. But as the supply of qualified personnel diminishes, their salaries will increase and more people will choose clinical laboratory science as a career. The problem is that it’s a reactive system and it takes a long time to self-correct. We needed to be proactive. One of the reasons why individual health systems are able to find and train people in the field is they’re close to the students and they’re telling them, “We need you. We’ll pay you to be trained. We’ll pay when you get out, and this is how much.” Financial incentives are helping. But we’re in for a rough time.

To echo what was said about instrumentation and middleware—in our freestanding emergency departments we are utilizing one of the newer, small Beckman Coulter instruments that has a smart quality control system and middleware, and it’s a model we thought about for oncology clinics. That combined with the ability to use telemedicine, telehealth, telepathology—if you’re getting alerts from your instrument, the blood smear images can be transmitted to a tech specialist who can look at the cells. There are really sick patients coming into these remote sites and the analyzers are smart and they essentially kick out, “Not sure what’s going on.” That means somebody has to realize “not sure what’s going on” could be acute leukemia; it could be a real medical emergency like promyelocytic leukemia. We need to leverage those smart systems with centralization of expert technical personnel and pathologists and leverage our ever-improving imaging technology in hematology.

An emergency room physician told me he didn’t understand what the problem was with resulting 100 percent of CBCs. He was at a remote site with no technologists—nurses performed the testing—and didn’t understand why the analyzers didn’t give him a number for every analyte in a CBC every time. He said, “It’s just a Simple Simon CBC.” And I said, “Oh no, there is no Simple Simon CBC.” This tells you something about the gap between what we do in the laboratory to produce high-quality results and doctors who think anyone should be able to churn out numbers off an analyzer. I’m a chemist but I have tremendous respect for CBC analyzers and hematology specialists. CBCs can be complex, especially if they require technologist or pathologist slide review. It’s not cookie-cutter.

Dr. Valcour

André, how has your work changed in the past half-dozen years or so in terms of assembling ever-greater expertise and counsel across the vast testing world of Labcorp?

Dr. Valcour (Labcorp): We understand it’s going to be a crunch to get highly competent, highly trained technologists. There’s no light at the end of the tunnel in the near term. What I’ve seen over the past 30 years—but even more in the past few years—is we’ve leveraged advanced intelligent middleware capabilities to eliminate redundant and tedious aspects of laboratory medicine. When you process 100,000 chemistries a night, no one’s looking at every calcium and albumin. So we’ve leveraged a lot of information technology, elegant autoverification capability, and advanced quality control systems so technologists are available to do the things that only qualified technologists can do. You still have to have trained technologists in a hematology department, for example, even with advanced digital imaging capability. We push the exceptional technologists we have to some of the areas where we haven’t found fully automated solutions. But every day we find new ways to build quality systems and IT solutions to free up our technologists from things a computer can do. We don’t see another near-term solution.

Ed, tell us about the importance of IT at Werfen.

Edward Bass (Werfen): IT is one of the keys to providing results to the hospital laboratory information system. We have a middleware program called Quanta Link. It consolidates the results and QC information from our instruments into one computer, and requires a single LIS interface to broadcast and share information. It’s bidirectional communication. We’re finding it is crucial to provide that type of service rather than five or six independent connections. Having a single point to look at all your QC results from all your instruments is a key workflow savings.

Cybersecurity is another area we’re spending a lot of time on. Using our data management system, we have a single connection that can help block transmission of nefarious programs.

I’ve been in conversations on whether the increasing costs of labor and cybersecurity might be eating up incredible percentages of laboratory budgets in the near term. Would you agree with that, Brooke?

Brooke Medaugh (Horiba): Yes. We’ve had to provide a solution for our customers by creating a middleware solution for our benchtop instruments to connect directly to an EHR and LIS that can handle multiple instruments filtering through one connection point. Our LiteDM software has a purpose similar to what Ed described, without a monthly fee. We’ve also renewed our ISO 27001 certification for information security; this is important particularly because we have remote connections to customer systems for technical support.

André, I’m sure cybersecurity is uppermost in the minds of Labcorp executives. Could you describe your approach to this?

Dr. Valcour (Labcorp): It’s critical. We invest in high-end IT capability to protect our systems and patient information.

The testing is not the single thing that makes our laboratory unique and different. We also focus on logistics and IT. Our investments are all around information transfer, enhancing information, quality of information. I don’t worry much about the machines or reagents. We know if we follow good-quality practices as stipulated by the CAP and in CLIA, we’re putting out good results on the machines. The question is getting the sample on the machine and getting the result to the doctor and making sure the result is in a format that’s educational for the doctor and not confusing. On the other side is making sure we get paid for it, and there’s a whole IT infrastructure for that too. We’re long past being just a testing company; we’re an information company.

Garegnani

Shannon, is it music to your ears to know you’re doing a great job with the instrumentation, or is it yet another task for which you feel you need to shoulder some of the burden with your customers who are providers?

Shannon Garegnani (Beckman Coulter): We’re not seeing that environment anymore where labs are only purchasing equipment. We’re seeing labs look for automation—informatics plus instrumentation, an intelligent solution that will give them the most benefit to address the issues we’ve discussed so far—staffing, lack of expertise, especially in small facilities or rural areas, and managing quality across multiple platforms in a high-volume environment.

We see clinical informatics being a huge piece of the puzzle—to have a consolidated interface, see everything that is happening, manage quality control, troubleshoot instruments remotely, and move beyond just autoverification. We look to our DxA 5000 family with scalable preanalytics, postanalytics, and informatics to offer customer-unique configurations that address their specific problems. With the DxA 5000 Fit we can now provide automation to all.

Historically automation has not been an option for low- and mid-volume hospitals, primarily due to cost. We now have solutions for those hospitals. Because Beckman Coulter offers every discipline, we can provide a harmonized experience and provide customers a single point of contact.

Ed, we said earlier we didn’t think Marcus Welby should be running your systems in his office. What about the results from your systems when they hit Marcus Welby? Do you worry about the physicians doing the right thing with the result?

Edward Bass (Werfen): Absolutely. With autoimmunity, there are many different disease states. The symptoms overlap, the results tend to overlap, and we have what we call a seronegative gap with today’s testing analytes. That’s why it’s important to build a precision medicine component, which would provide the physician with the proper guidance to use those results. We are developing many new, novel tests that would help close the seronegative gap. That is a key focus for our company.

Susan, what are your thoughts on what ordering physicians do with the results the laboratories supply?

Dr. Fuhrman (formerly OhioHealth): It depends on the physician. I was in a facility that had specialists who were to a large extent taking care of or consulting on the patients. I remember a blood bank issue I had with a difficult surgical patient who was bleeding profusely with iatrogenic coagulopathy—the patient was over-anticoagulated—and a medical disorder that was causing a severe peripheral vascular clotting problem that required surgical intervention, and talking to the surgeons was very difficult. It was especially problematic because the patient had antibodies such that compatible blood could not initially be located. I told them I thought they needed to get a hematology consult, and they did. It was like night and day being able to speak with the hematologist, who really understood the ramifications of the coagulation test results as well as the transfusion medicine issue. Although it’s sometimes hard to get people to the right doctor, it’s as Ed said—family practice physicians shouldn’t be interpreting IFA panels.

Some health systems restrict ordering of some tests to specialists. There are pros and cons to that and it feels a lot like Big Brother, which is why I like to take a personal approach and steer providers to consult with the right specialist physicians. Also, physicians have difficulty unless the lab results are clear. Let me refer back to the Simple Simon CBC. If you put out a message that says, “Abnormal cells identified. Interpret white blood cell count with caution”—they’re not going to understand that may mean there are blasts in the blood. They will likely look at the value we produce and not consider acute leukemia as a possibility. Of course, it depends on the situation. In most cases a qualified technologist would review the slide and, if appropriate, speak with the provider and/or have a pathologist review the slide. But if you’re at a site like a freestanding ED or outpatient satellite lab with no qualified technologists to review slides for morphology, you better be very careful how you report those types of results. In this example we should be as specific as we can and use the term “possible blasts,” if that is what the analyzer is flagging the result for. We should always give our clinicians as much information as we can accurately produce and our reports should be as clear as we can make them. If we just report “cannot accurately assess WBC” and not report a number or say why, many providers will assume it’s a lab glitch and not consider that this is, in itself, a significant finding. We need to make sure our reports reflect what we do know and not leave our clinicians guessing.

And getting back to the IT issue, we need to know as pathologists what our product looks like when the clinicians are viewing their patients’ results. I looked at results on Epic’s Haiku system. They call it Haiku because it was really abbreviated—no reference ranges, no units. It was hard to see the comments. It’s important for laboratorians to look at results the way their clinicians are looking at results so they can understand where gaps are and how to fill them in. As a result of our review of Haiku, Epic improved it substantially. That’s our responsibility as laboratorians.

André, I’m sure this is a prominent issue at Labcorp.

Dr. Valcour (Labcorp): The diagnostic industry has to do a better job of ensuring transferability of results and harmonization of methods so if a doctor sends a test to one institution and gets a result and sends it to another institution, they can be followed and understood. There’s a lot of testing for which we need to do a better job of harmonizing methods.

One of the things I’m proud of at Labcorp and I’m intimately involved in is building clinical decision support algorithms to help doctors understand the results we provide. I oversee hemostasis testing for the reference lab in Burlington. When we send a report, we send an interpretation that is patient-centric. It’s not, “refer to a table” or “refer to a website.” It’s, “Your patient had these values, and these values are most consistent with this condition.” Doing that for every hemostasis result is critical because we cannot assume every clinician is an expert in hemostasis.

I also oversee allergy testing. Allergy has evolved to what’s called molecular allergology, where not only do you look at allergy to peanut, you can look at allergy to six molecular components, individual allergens within peanut. The problem is a doctor who’s looking at a result doesn’t necessarily know what all the components mean clinically. Is the patient truly allergic to peanut? Is this patient cross-reactive with birch tree pollen, which has a component that is similar to one of the major allergens in peanut? If you get a result that’s positive to peanut and if the clinician is unknowledgeable, the patient might end up avoiding peanut when they don’t have to. We provide advanced testing and clinical decision support, patient-centric interpretive reporting, that allow the clinician to understand the result. Not knowing the patient clinically, we can’t say exactly what the patient has, but based on these results we can say the most likely scenario is this patient is truly allergic to birch trees and not peanut, or is in fact likely to be allergic to peanut.

Doctors have too much on their plates to know everything about the results we generate. Laboratories should be able to deliver clinical decision support for complicated tests.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management