How to make data in charts and graphs ‘more consumable’

January 2023—The acclaimed film composer John Powell said, “Communication works for those who work at it.” A sentiment to which Yonah Ziemba, MD, adhered when communicating data via charts, graphs, and tables during his pathology fellowship—benefiting himself and others.

“In pathology, our data is deeper and richer, so if we get better at presenting our data, we will have a very important seat at the table,” says Dr. Ziemba, assistant professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Northwell Health, New Hyde Park, NY.

During his pathology fellowship at Northwell, he explains, “I started noticing that everyone realizes when they need help accessing data, because if you don’t have it, you don’t have it. But not everyone realizes when they need help with how to present the data.”

This led Dr. Ziemba to research data visualization for his own presentation purposes and to help colleagues redesign their charts and graphs to be easier to understand and more impactful. Over time, he developed a set of tips to help pathologists avoid common data-visualization mistakes.

Darci Block, PhD, laboratory director for the central clinical laboratory at Mayo Clinic, attended Dr. Ziemba’s data-visualization presentation at the Association of Pathology Informatics’ 2022 Pathology Informatics Summit. She was sufficiently impressed that she invited him to speak at a recent clinical chemistry grand rounds at Mayo Clinic.

“Our goal when we publish data should be to accurately represent it but also to make it more consumable,” Dr. Block says. “The improvements he suggests make data more consumable, which is, in turn, going to help people better appreciate the message of the presentation or publication.”

Following are common data-visualization mistakes in pathology, according to Dr. Ziemba, and tips for avoiding them.

Dr. Ziemba

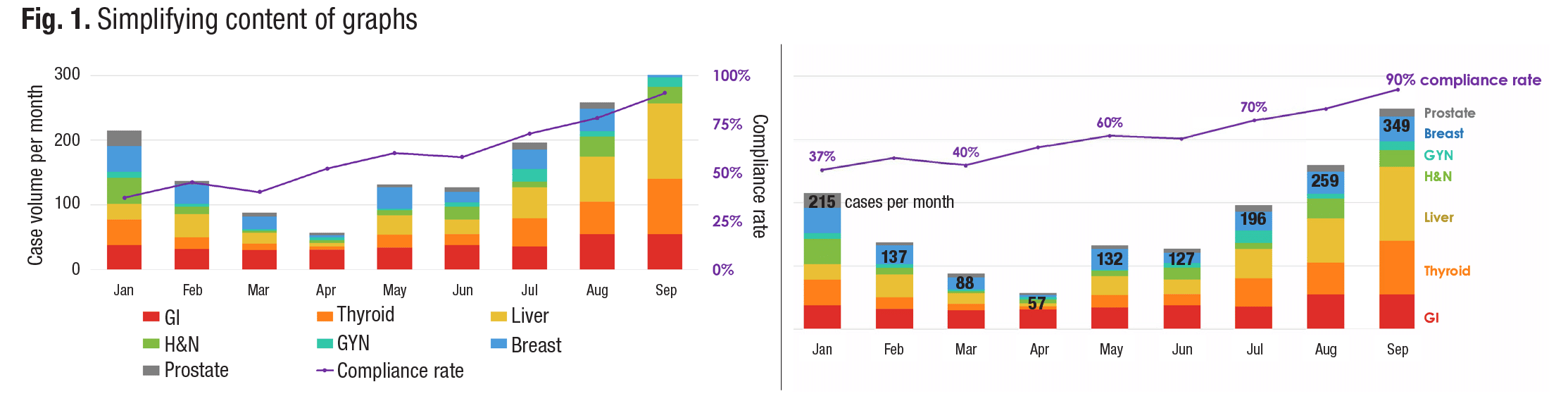

Multiple axes. One of the most visually confusing components of a graph are vertical axes on the left and right sides displaying different types of measurements, Dr. Ziemba says. This often occurs when two representations are superimposed, such as when a line graph showing the monthly percentage of pathology reports processed within a two-day turnaround is superimposed on a bar chart listing total pathology cases each month. While it sometimes makes sense to superimpose data, he continues, requiring people to draw a mental line to one side of the chart and then another mental line to the other side is too much to ask.

The simple solution: Label the line graph and bar chart directly, Dr. Ziemba says. If there were 137 pathology cases in February, for example, place the number 137 above or inside the February bar in the chart. This way, people viewing the chart do not have to draw imaginary lines to the side of the page to try to figure out the height of the February bar. Label key data points in the line graph in a similar manner, he says (Fig. 1).

At left, a double-axis graph with a legend and axes labels, which has a significant cognitive load. At right, a double-axis graph in which the legend has been replaced with color-coded descriptors and the axes labels with numerals on the corresponding visual elements to allow viewers to absorb the information with less cognitive effort.

The legend. A legend might seem like a helpful way to identify various elements in a chart or graph, but it forces viewers to look away from a graphic to find the labels they need, Dr. Ziemba says. Instead, he advises, color code and label each component. If, for example, a pathologist labeled a green slice of pie “chemistry” and a blue slice of pie “hematology” in a pie chart of pathology test volumes, the viewer could quickly and easily digest the information without having to scan the legend to determine what each color represents.

The process of looking back and forth from a chart to a legend requires conscious effort, Dr. Ziemba says. This conflicts with the data-visualization goal of designing charts with preattentive attributes, which are features that people will automatically understand before they realize they are paying attention.

Three-dimensional displays. While three-dimensional imagery may make figures in a chart pop from the page, it can also create visual distortion, Dr. Ziemba warns. Imagine if a 3D pie chart were lying on the ground. A 21 percent slice of pie in the foreground would look significantly larger than a 21 percent slice on the far side of the pie (Fig. 2).

In a similar manner, “if you are looking down from the top of the Empire State Building at the other skyscrapers,” he says, “they suddenly don’t look as tall as they did when you were on the sidewalk. It’s the same type of thing.”

At left, use of three-dimensional graphics distorts the slices of the pie chart, making the green slice appear larger than the identically sized yellow slice. At right, the lack of 3D graphics makes it clear that the yellow and green slices of the pie chart are the same size.

Bar charts can also be distorted by 3D graphics, Dr. Ziemba says. When bars are rendered in 3D, the depth of a pillar can appear to add to its height, making it harder for viewers to discern where the top of the bar ends.

Long vertical labels. Bar graphs are often displayed as a group of vertical bars, but when each bar has a long textual label, the graphic may benefit from a horizontal orientation, Dr. Ziemba says. If each bar in a bar graph represents the number of cases of a specific disease—plasma cell leukemia, mantle cell lymphoma, and pure red cell aplasia, for example—it could be difficult to fit each disease name under a vertical bar in a graph. By turning the graph on its side, long disease names can run horizontally to the left of horizontal bars and still allow room for the varying lengths of the bars (Fig. 3).

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management