Strongyloides rhabditiform larvae should be distinguished from hookworm rhabditiform larvae. The two are often mistaken for one another, she said, and both can appear in stool specimens. Strongyloides rhabditiform larvae are usually the diagnostic form for strongyloidiasis.

“The way we tell them apart is by looking at their mouth and at their genital primordium,” she said (Fig. 8). The Strongyloides on the left has a short buccal cavity, compared with the hookworm on the right, which has a long one. “Long is defined as greater than one-third of the total diameter of the worm itself.” The Strongyloides has a prominent genital primordium, and the hookworm, an inconspicuous one. Otherwise, the two are similar in size and shape.

Bobbi Pritt, MD, MSc, DTM&H, director of the clinical parasitology laboratory at Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, views the hookworm versus Strongyloides distinction as “a big deal.” “Strongyloides doesn’t respond to the drug that’s used for hookworm,” she said in an interview, “but Strongyloides can be life-threatening, so you want to get the treatment right.”

Gary Weil, MD, professor of medicine at Washington University School of Medicine, says the hookworm drugs they usually give are albendazole or mebendazole, “and those have very limited activity against Strongyloides. The best drug for Strongyloides is ivermectin, but it is not very good for treating hookworm infections.”

Dr. Ribes shared a case in which a 33-year-old man from Thailand was losing weight and had a chronic cough producing non-bloody sputum. Three sputa specimens tested negative for acid-fast bacilli, but the fluorescent stain displayed large fluorescent green structures that weren’t rod-shaped bacteria. When Dr. Ribes and colleagues looked at the structures under light microscopy, they saw operculated eggs with little shoulders. The abopercular ends didn’t have knobs. The patient’s sputum exhibited Paragonimus species eggs. For comparison, Dr. Ribes showed an image of a Paragonimus egg on the left and a Diphyllobothrium species egg on the right (Fig. 9). The eggs, she said, can be confused for one another in stool specimens. “You are never going to find Diphyllobothrium eggs in a respiratory specimen, so there knowing your life cycle is probably a good thing,” Dr. Ribes said. “But for your boards and your recredentialing, the differences are that your Diphyllobothrium eggs tend to be a little wider and a little shorter.” They also have an operculum with no shoulders, and an abopercular knob seen at that lower arrow.

The patient’s sputum exhibited Paragonimus species eggs. For comparison, Dr. Ribes showed an image of a Paragonimus egg on the left and a Diphyllobothrium species egg on the right (Fig. 9). The eggs, she said, can be confused for one another in stool specimens. “You are never going to find Diphyllobothrium eggs in a respiratory specimen, so there knowing your life cycle is probably a good thing,” Dr. Ribes said. “But for your boards and your recredentialing, the differences are that your Diphyllobothrium eggs tend to be a little wider and a little shorter.” They also have an operculum with no shoulders, and an abopercular knob seen at that lower arrow.

Paragonimus eggs, however, do have a flattened operculum that has raised shoulders. The abopercular end lacks a knob, but it may be slightly “more pointy and may be a little bit thickened,” Dr. Ribes said. “They tend to overall have a longer length distribution and are a little thinner than your Diphyllobothrium eggs.”

The life cycle of Paragonimus is complicated and involves snails, Dr. Ribes said. “Among the more than 10 species reported to infect humans, the most common is P. westermani, the oriental lung fluke,” says a CDC document that provides a diagram of the Paragonimus life cycle (Fig. 10).

Washington University’s Dr. Weil says paragonimiasis occurs “on every continent, but it is most important in Asia, especially in East Asia, where some 25 million people are estimated to be infected.” People become infected when they consume undercooked or uncooked crayfish or freshwater crabs. “The crustaceans are an intermediate host for the parasite, and their flesh contains larvae that infect mammals, including humans.” The larvae migrate into the lungs, evolving into adult worms over a span of months. In North America, the parasite is found only in freshwater crayfish, he says.

Paragonimus is a hermaphrodite, Dr. Ribes said, “so both sexes in the same worm, but they are social animals. They like to have a bud, so when they first are coming into the body and are maturing in the hepatic veins, they pair up and then they migrate off to where they are going to live in perpetuity. Those that find no love may wander to other tissues like brain, where they can cause trouble such as creating seizures.”

Paragonimus is a hermaphrodite, Dr. Ribes said, “so both sexes in the same worm, but they are social animals. They like to have a bud, so when they first are coming into the body and are maturing in the hepatic veins, they pair up and then they migrate off to where they are going to live in perpetuity. Those that find no love may wander to other tissues like brain, where they can cause trouble such as creating seizures.”

“The diagnosis of paragonimiasis,” she says, “may be made either on the basis of eggs or the fluke. Eggs can be seen in the sputum, or coughed up, swallowed, and then passed in the stool. Or they can be identified in the lung on biopsy or in the fluke’s uterine horns.”

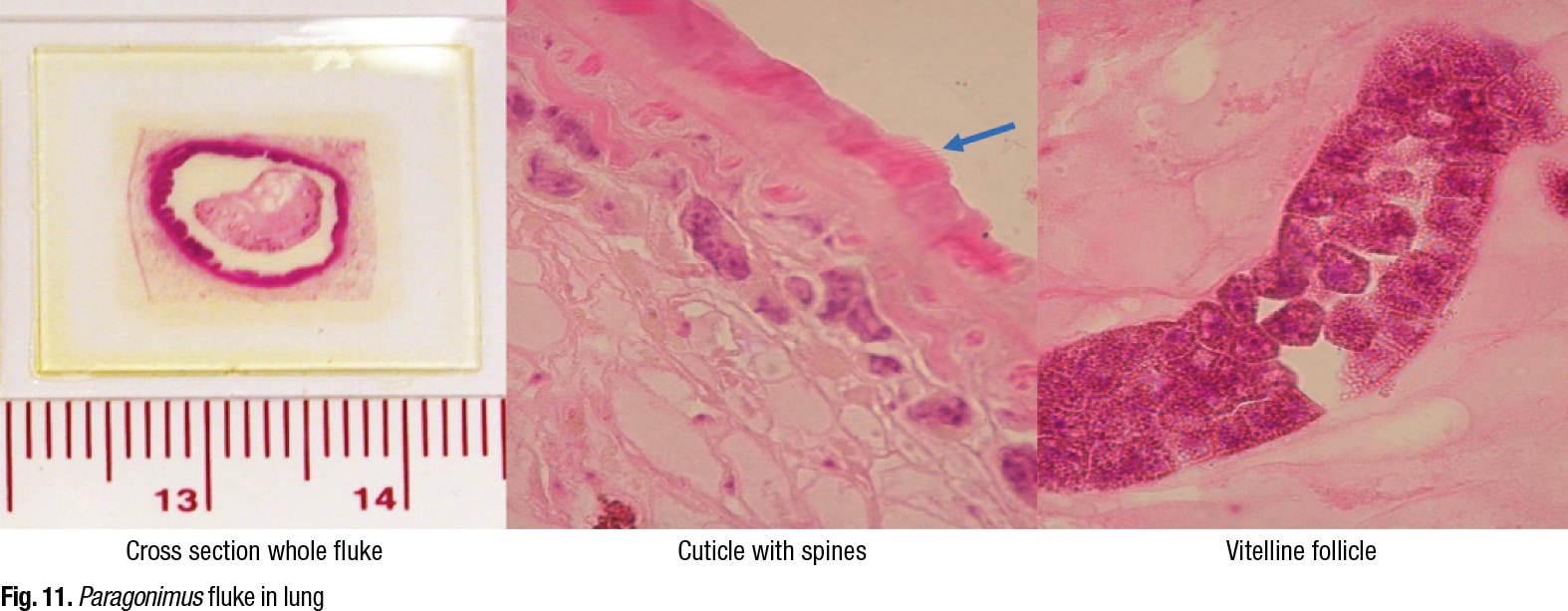

Two adult flukes generally encyst in well-developed capsules in the lung parenchyma. Adults are 4–6 mm wide and 7.5–12 mm long. The flukes have suckers, pink spines, vitellaria, ovaries, testes, and a uterus with eggs.

Dr. Ribes shared a cross section of a whole Paragonimus fluke in the lung, emphasizing that there are multiple different sections of the fluke that the tissue slice can go through (Fig. 11). She pointed to a cuticle with spines on it and to vitelline follicles. “But in this particular slice, we weren’t lucky. There is no uterus, so we don’t see any eggs.” However, “We can look for eggs within this fibrous capsule,” she said, pointing to the structure on the left side. “Or we may be able to identify eggs extravasating through the tissues into the lung parenchyma itself into the alveolar space.”

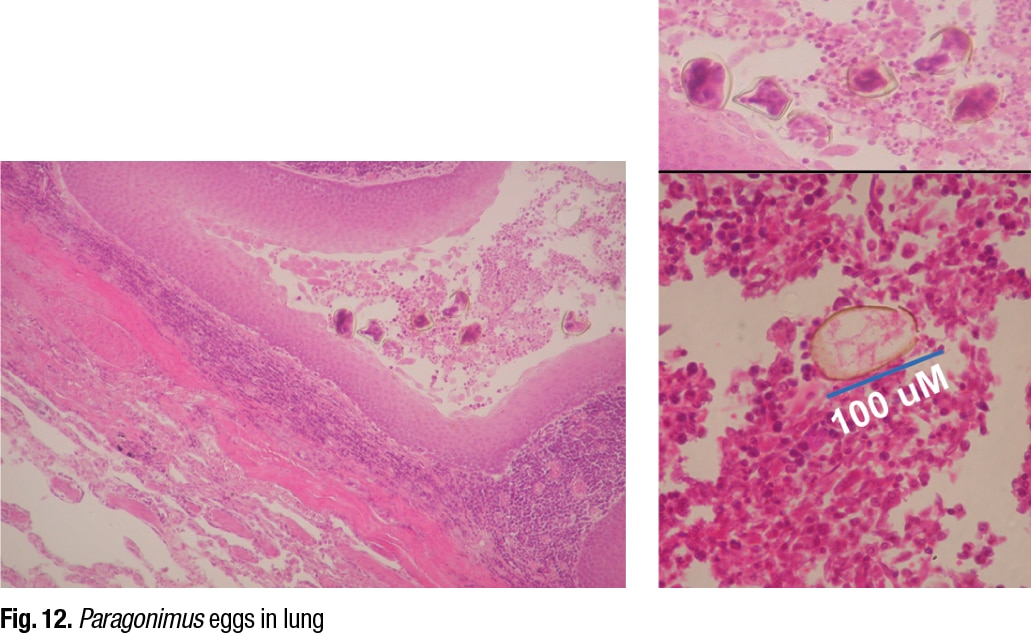

She displayed an image of Paragonimus eggs in the lung (Fig. 12), noting that the eggs are distorted because of the microtome, which is more obvious in the enlarged picture on the upper right. “We are not going to make an identification of Paragonimus based on these distorted egg structures. We might based on this,” she said, indicating the egg in the lower right image. “Here is our operculum, and there is our size distribution, location in the lung. We are good to go. We have identified this as Paragonimus species. Not necessarily anything beyond that.”

What about other testing for Paragonimus? Dr. Weil says his colleague Peter Fischer, PhD, MS, also a professor of medicine at Washington University, developed about nine years ago an antibody test for paragonimiasis, and they shared the antigen with the CDC a year or so later (Fischer PU, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88[6]:1035–1040). “Adult worms from gerbils were used to prepare an antigen for use in an antibody test,” Dr. Weil says. “Later work led to identification of a recombinant antigen that can be used instead of the native worm antigen.”

What about other testing for Paragonimus? Dr. Weil says his colleague Peter Fischer, PhD, MS, also a professor of medicine at Washington University, developed about nine years ago an antibody test for paragonimiasis, and they shared the antigen with the CDC a year or so later (Fischer PU, et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88[6]:1035–1040). “Adult worms from gerbils were used to prepare an antigen for use in an antibody test,” Dr. Weil says. “Later work led to identification of a recombinant antigen that can be used instead of the native worm antigen.”

The CDC, Dr. Fischer told CAP TODAY in an interview, is evaluating how the antibody test performs with its large sera collections, though the agency hasn’t published its findings yet. “Our work,” says Dr. Weil, “has focused on serology with samples from North American cases, but the test also works well with sera from patients with paragonimiasis from other regions.” He notes that the serology test is highly sensitive, but they have tested only a limited quantity of samples because human infections are infrequent in North America.

“While molecular [DNA detection] tests can be helpful,” Dr. Fischer says, “PCR of sputum or stool may provide a false-negative result because the worms cause illness long before they reach maturity and produce eggs that are shed in sputum or stool.”

Karen Lusky is a writer in Brentwood, Tenn.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management