Charna Albert

June 2023—For HIV and HCV algorithmic testing, the workflow options have risks to consider. Molecular testing performed as an automatic reflex on the same sample used for the serologic testing risks carryover contamination, and requiring a dedicated sample for the molecular assay risks incomplete testing.

Whatever approach the laboratory decides to take for HIV and HCV testing, don’t assume full physician compliance with the complicated algorithms and don’t “go it alone” when making lab-driven algorithms, said Neil W. Anderson, MD, D(ABMM), associate professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, in an AACC session last year. He explained why and how the laboratory at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, where he is medical director of the molecular infectious disease laboratory and assistant medical director of the microbiology laboratory, made its own calls for both algorithms.

The testing algorithm for HIV begins with a fourth-generation HIV-1/2 antigen/antibody combination immunoassay to detect IgG and IgM to HIV-1 and HIV-2 and to detect the p24 antigen of HIV-1. “It’s a specialized test, with both antibody and antigen detection,” he noted.

If the fourth-generation Ag/Ab assay result is positive or reactive, “we perform the HIV-1/HIV-2 antibody differentiation immunoassay.” If it’s negative or indeterminate, “we need a third tiebreaker test, and that has to be an HIV-1 nucleic acid amplification test.”

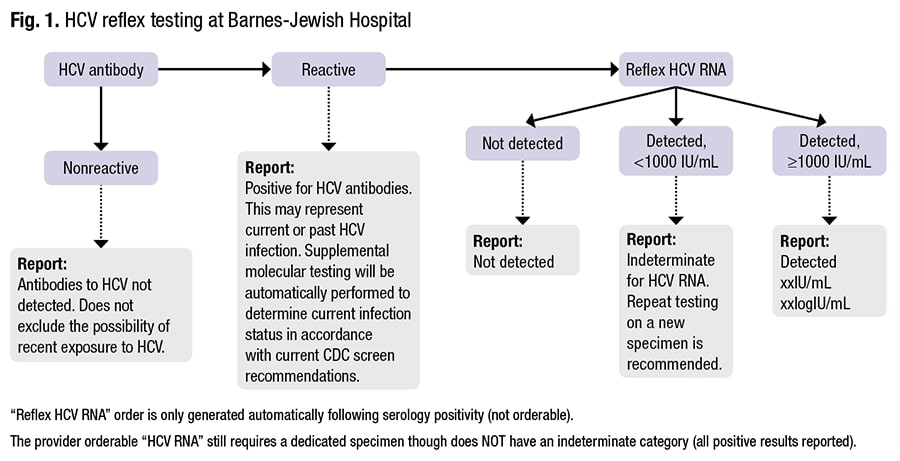

For HCV algorithmic testing, “there are additional nuances to keep in mind,” Dr. Anderson said. It begins with HCV antibody testing. “All HCV serologic tests detect IgG. Some also detect IgM, but they don’t differentiate between the two.” The serologic assays are reported as reactive or nonreactive, though some manufacturers have indeterminate or equivocal callouts. In contrast to patients with HIV, HCV patients are serologically positive much later—typically around eight to 12 weeks post-infection. “And there’s a lot more variability in time to positivity.”

Dr. Anderson

With a nonreactive antibody test, the result is interpreted as likely negative for infection. “However, if there is a strong pretest probability of infection”—the patient is an IV drug user with reported recent use, for example—“we would recommend follow-up testing using a molecular approach, because there’s a chance they may not have seroconverted yet.”

A reactive antibody test could be a false-positive or the patient could have cleared the virus, which approximately 10 percent of HCV patients will do spontaneously. If the initial test is reactive, the next step is confirmatory HCV RNA-based testing. If that test is positive and a viral load is detected, “then that patient has HCV and testing is done.” If no viral load is detected, they probably do not have HCV. “But there are some nuances there, and it helps to understand the viral load dynamics to understand why it’s nuanced.”

From the point at which the antibody is positive, HCV viral loads can fluctuate (within the first six months of infection), possibly falling to below detectable levels. A patient might test “not detected” despite having an active infection, he said. So if the patient has strong risk factors for HCV, “you’re going to want to consider repeating that viral load, typically within six months.”

Algorithmic testing works best when performed automatically on a single specimen, but transferring specimens from the serologic to the molecular laboratory can be challenging, Dr. Anderson said, “even when all testing is available under the same roof.” Another challenge: the different specimen-handling practices of the two labs.In one of the earlier studies of the potential for viral contamination of a total lab automation system, Bryan, et al., took environmental swabs followed by PCR for HBV and HCV from a chemistry TLA system during routine clinical use and after running a small number of high-titer HCV samples. Of 79 baseline swabs for nucleic acids performed on the TLA system, 10 were positive for HBV and eight for HCV, with tube decapping and tube manipulation the sites of greatest risk (Bryan A, et al. Clin Chem. 2016;62[7]:973–981).

“So are you going to require an additional dedicated sample for molecular testing, or are you going to perform all the testing on the same specimen?” Dr. Anderson asked, noting each lab will have its own “right answer.”

“If you’re going to do all the testing on one specimen, it’s easy to get all that testing done, but you do have that risk of contamination. If you require the dedicated specimen, you’re going to mitigate a lot of that contamination risk, but now you’re creating a different risk—you’re at risk for incomplete testing.” For laboratories that require additional specimens or orders, “I would recommend you have something in place to notify the provider, probably more actively than just reporting it in the electronic medical record. You might need a callback, so they know the testing on that patient is incomplete.”

Dr. Anderson explained how Barnes-Jewish Hospital, with its core lab on floor four and its molecular infectious disease lab on floor five, “did the math” this decision requires. HIV-1/2 differentiation assay testing is automatically performed for every reactive fourth-generation assay screen. “These instruments both live in our serology lab—they sit right next to each other. If we have a reactive fourth gen, our technologists know they need to do the differentiation assay.”

Making sure providers “stay on algorithm,” is important, he said. “We do not offer the HIV-1/HIV-2 differentiation assay [Geenius] as a standalone order because we don’t want people bypassing the route of testing they need to do. Because this is an automatic reflex, and it’s all done on the same specimen, our compliance here is virtually 100 percent.” Turnaround time for the differentiation assay, which is monitored, is one hour. “We had a lot of confusing instances where we would communicate the antigen/antibody result to our providers and then the differentiation assay required an additional specimen, or then the diagnosis was confirmed and we wanted to call that back too.” To prevent confusion and with the TAT now one hour, for most clinical locations the call is made only after the differentiation assay result is available. “And our providers are okay with that.” Obstetrics at their institution is one exception, he noted. “They want to know when the antigen/antibody assay results are available because they have to make very quick decisions if labor is imminent.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management