CAP TODAY and the Association for Molecular Pathology have teamed up to bring molecular case reports to CAP TODAY readers. AMP members write the reports using clinical cases from their own practices that show molecular testing’s important role in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. The following report comes from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. If you would like to submit a case report, please send an email to the AMP at amp@amp.org. For more information about the AMP and all previously published case reports, visit www.amp.org.

Edwin Kamau, PhD; Tara Narasumhalu, MD

Omai Garner, PhD; Abie H. Mendelsohn, MD

Jeffrey D. Goldstein, MD; Shangxin Yang, PhD

January 2022—A 33-year-old male with progressive hoarseness and shortness of breath was given a purported diagnosis of laryngeal papillomatosis and referred to our institution in November 2020 for a higher level of care. On presentation, the patient reported no recent upper respiratory infection-like systemic symptoms but had cough, nasal congestion, throat discomfort, dysphonia, and worsening dyspnea. About two months prior, the patient’s planned diagnostic direct laryngoscopy was aborted intraoperatively as he could not be intubated with subsequent airway compromise, and therefore the planned procedure was not completed. The patient’s travel and immigration history was not obtained, but he was born in Oaxaca, Mexico and had had symptoms that waxed and waned since he was 17 years old.

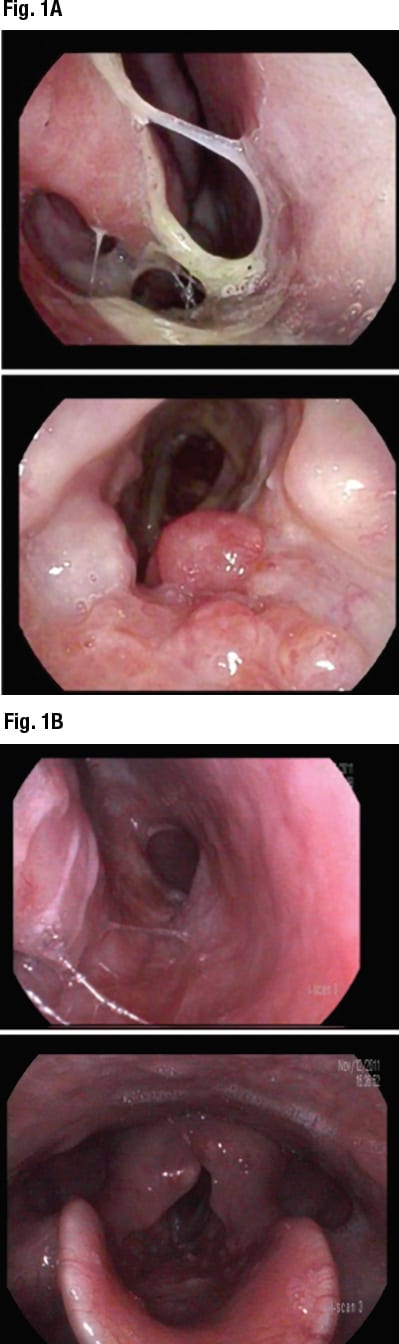

At the initial consultation with our service, laryngostroboscopy revealed unrestricted vocal cord movement but demonstrated approximately 75 percent subglottic stenosis that had highly irregular mucosa with thickened mucus throughout the upper airway, and multiple dimpled points of hypertrophic mucosa (Fig. 1A). The initial differential diagnosis included connective tissue disorders, infectious processes, or neoplasms. Surgery was urgently recommended to treat the narrowed airway and obtain biopsy tissue for diagnosis.

Surgery performed was a direct laryngoscopy with use of controlled radial expansion balloon dilation of tracheal stenosis, biopsy and debulking of laryngeal lesions, and nasal endoscopy with biopsy of left inferior turbinate polypoid lesion. Biopsy specimens were submitted for histopathological examination, and a surgical swab was submitted to the microbiology laboratory for fungal and bacterial cultures.

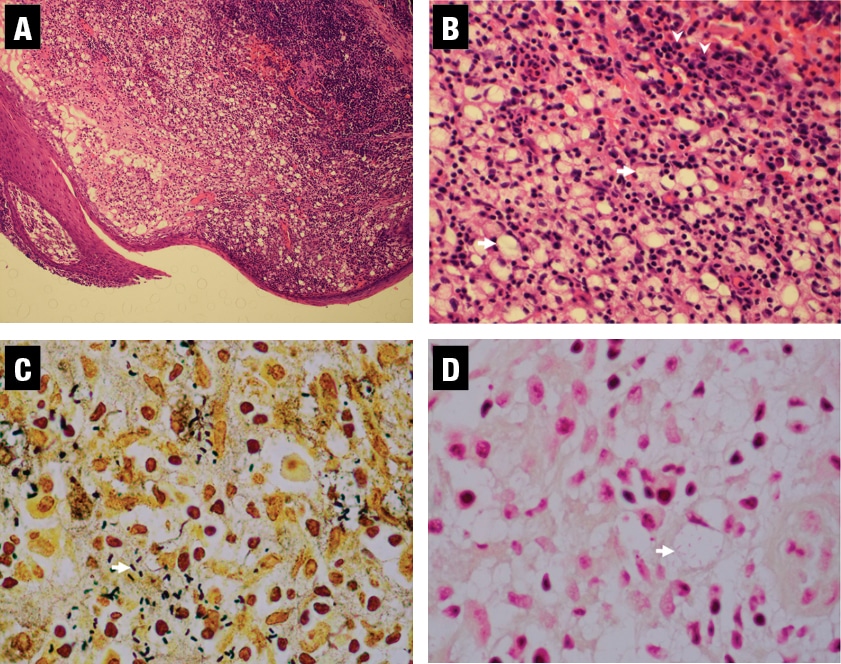

Details of the pathology. Hematoxylin-eosin–stained sections of the laryngeal biopsies showed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate beneath an intact squamous epithelium. The infiltrate contained numerous characteristic vacuolated macrophages with clear cytoplasm (Mikulicz cells, Fig. 2B, arrows), together with plasma cells (Fig. 2B, arrowheads), lymphocytes, and scattered neutrophils. The Mikulicz cells contained numerous bacilli as highlighted by Warthin-Starry stain (Fig. 2C, arrow). Tissue Gram stain showed that the intracytoplasmic bacilli within the histiocytes were faintly Gram-negative (Fig. 2D, arrow).

Fig. 1. Images taken during laryngostroboscopy. Panel A showed complete glottal closure and 75 percent subglottic stenosis observed with highly irregular mucosa present with thickened mucus throughout the upper airway, and multiple spots of hypertrophic mucosa. Panel B showed much improved appearance of laryngeal mucosa with dramatically reduced inflammation after the surgery and antibiotic treatment.

Details of the microbiology. Bacterial cultures grew a moderate amount of Klebsiella pneumoniae and a few colonies of Staphylococcus aureus, both pan-susceptible to antibiotics tested. These organisms were identified using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Vitek MS, BioMérieux), and drug susceptibility was performed and interpreted per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. The presence of intracellular bacilli within Mikulicz cells in laryngeal papillomas, combined with positive culture of K. pneumoniae, increased the suspicion that the infectious etiology responsible for this condition was K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, the most common causative agent for rhinoscleroma. However, the current FDA-approved Vitek MS database (v3.2) cannot differentiate K. pneumoniae subspecies including rhinoscleromatis.

Molecular analysis. To confirm our preliminary diagnosis, we performed whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis of the isolate (UCLA557) on MiSeq (Illumina), using 2 × 250 bp protocol and analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench (Qiagen), following a recently validated workflow.1 Briefly, raw sequences were trimmed and paired by the CLC Genomics Workbench where de novo sequence assembly was performed. Several contigs with a size range of 2,000–10,000 bp were extracted and analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) nr/nt database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to obtain an appropriate reference genome for mapping. The reference genome was downloaded to CLC Genomics Workbench where three target genes (i.e. 16S rRNA, rpoB, and groEL [hsp65]) were identified, extracted, and concatenated. The sequence reads were then mapped to the concatenated reference sequence. The consensus sequence of each target gene was then queried using the BLAST nr/nt database. The isolate was identified as K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis with 100 percent query coverage and 100 percent identity for all three target genes. Phylogenetic analysis of the WGS using k-mer tree clustering further confirmed UCLA557 to be K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis (Fig. 3). Notably, we found that the 16S rRNA gene sequence alone is insufficient to identify any subspecies of K. pneumoniae, as the BLAST results showed the exact same scores (100 percent coverage, 100 percent identity) for both K. pneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae, two closely related species.

Clinical impact. Pathological and microbiological results revealed our patient had rhinoscleroma, a granulomatous inflammatory condition caused by K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis. The dilation of tracheal stenosis and debulking of laryngeal polyps and nasal left inferior turbinate polyps greatly improved the patient’s symptoms (Fig. 1B). After the diagnosis, the patient was prescribed long-term therapy of doxycycline and ciprofloxacin.

Discussion. Rhinoscleroma is a chronic and slowly progressive granulomatous infection of the nose and upper respiratory tract that has histopathological features consisting of Mikulicz cells, Russell bodies, and Gram-negative bacilli.2 K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis is the main causative agent, but K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae may also be responsible in rare cases.2,3 The infection is contracted by inhaling droplets containing the bacteria, with the disease typically appearing in young adults, although recent data does not support specific age patterns.4 Studies have shown a possible genetic predisposition, which may arise from a particular immunodeficiency.5,6 Rhinoscleroma is endemic in Central and South America, parts of Africa, the Middle East, China, India, the Philippines, and Central and Eastern Europe, and is mostly associated with low economic status.7 Although the disease is extremely rare in nonendemic countries and mostly found in immigrants, it is imperative to recognize and correctly diagnose the infection to subspecies level since specialized prolonged antibiotic treatment is required, typically three to nine months.5 Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are the drugs of choice, but other drugs such as rifampin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and third-generation cephalosporins have been used.5,7,8 Treatment may also involve surgical debridement, and steroids can improve the acute inflammatory symptoms.

Clinically, rhinoscleroma generally has three disease stages, including a relatively short (weeks to months) catarrhal-atrophic stage in which patients typically present with rhinorrhea and recurrent sinusitis, a prolonged (months to years) granulomatous stage characterized by mass formation with tissue destruction, and a chronic sclerotic/fibrotic stage with extensive tissue scarring and fibrosis.2 In this case, our patient’s presentation was most consistent with the granulomatous stage, which can present with symptoms such as nosebleeds, nasal and/or respiratory tract obstruction, loss of sense of smell, a hoarse voice, and thickening or numbing of the soft palate.2,3 The diagnosis requires clinical correlation and is made by histological examination and confirmed by cultures. The differential diagnosis includes granulomatous bacterial, fungal, or protozoan infections present in endemic areas; vasculitis; and neoplastic processes affecting the nose and upper airways, including the lips and soft palate.2,3

Fig. 2. Pathological examination showed plasma cells, neutrophils, and vacuolated macrophages (Mikulicz cells) with intracellular organisms. Panels A and B are H&E stains of the laryngeal biopsy showing hyperplastic squamous mucosa with an underlying infiltrate of large cells with clear cytoplasm (arrows). The background inflammation consists predominantly of plasma cells (arrowheads) and scattered neutrophils (original magnification 100× and 400×, respectively). Panel C is a Warthin-Starry stain and Panel D a tissue Gram stain, both highlighting the bacilli within the cytoplasm of the Mikulicz cells (arrows, both original magnification 400×).

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management