The team then studied the patient records to see if the NGS results would have altered treatment. They looked at 11 patients for whom only the laboratory’s standard-of-care testing detected the infections. “What happens potentially,” they wanted to know, “when NGS can miss these pathogens and the routine results are not available?” Dr. Young said.

One patient had methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. “The empiric therapy before BAL collection would not have covered MRSA,” she said. The patient was prescribed vancomycin once the ICP results were in. “If that organism had not been found, the patient might not have been on an effective therapy,” Dr. Young said.

Another patient had Enterobacter aerogenes. The culture susceptibility profile was used to determine that the patient needed to be switched to cefepime to cover that organism, similar to yet another patient who had Pseudomonas aeruginosa for whom the culture susceptibility panel allowed the clinicians to deescalate from the empiric cefepime to levofloxacin. “In another example, our patient with Coccidioides was on voriconazole for empiric treatment, but voriconazole is inferior to amphotericin B in this setting,” she said. “And five of our six patients who had Pneumocystis were missed by NGS, and half of these would not have been treated at all or would have been treated suboptimally.”

Empiric therapy covers most opportunistic pneumonias in this population and is generally effective, she said, but it is not a replacement for susceptibility testing provided by culture. NGS doesn’t sequence deeply enough to find all the drug resistance genes. Ten of their patients then would not have been treated optimally had only NGS been used.

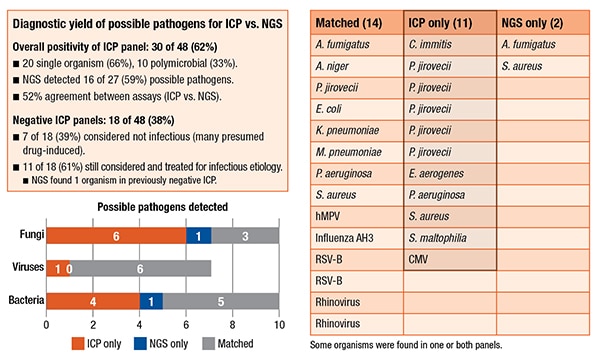

In other ways, however, their NGS assay did find more information than the ICP. There were 171 organisms in the 48 patients. Only 36 were true positives. (Taxonomer optimizes sensitivity over specificity, she pointed out, which creates a number of false-positives that have to be manually adjudicated using the Taxonomer score.) About 21 percent were adjudicated; 79 percent were not. The NGS assay was found to be slightly better at detecting viruses: 54 percent were adjudicated. It also detected two additional findings. In one patient who had a negative ICP, it found Aspergillus fumigatus. They also had a previously positive serum Galactomannan antigen test as well as a CT presentation that was “classic for Aspergillus. So the physicians were already treating the patient as an Aspergillus patient.” In another case, the NGS assay found an additional S. aureus and, in the culture, Enterobacter aerogenes grew, but there was also Gram-positive cocci on the Gram stain, so antibiotics would have covered that.

In other ways, however, their NGS assay did find more information than the ICP. There were 171 organisms in the 48 patients. Only 36 were true positives. (Taxonomer optimizes sensitivity over specificity, she pointed out, which creates a number of false-positives that have to be manually adjudicated using the Taxonomer score.) About 21 percent were adjudicated; 79 percent were not. The NGS assay was found to be slightly better at detecting viruses: 54 percent were adjudicated. It also detected two additional findings. In one patient who had a negative ICP, it found Aspergillus fumigatus. They also had a previously positive serum Galactomannan antigen test as well as a CT presentation that was “classic for Aspergillus. So the physicians were already treating the patient as an Aspergillus patient.” In another case, the NGS assay found an additional S. aureus and, in the culture, Enterobacter aerogenes grew, but there was also Gram-positive cocci on the Gram stain, so antibiotics would have covered that.

Their NGS assay also provides better resolution over the ICP. “We don’t normally differentiate our Candida species because they’re considered colonizers. But the NGS assay was able to detect and speciate Candida. It also specified some of the viral strains. So we think this may be useful for epidemiology studies,” Dr. Young said.

She listed the study’s limitations—small sample size, the use of frozen BAL specimens which may have affected analytical sensitivity, and the retrospective design—and provided the team’s main recommendation: The NGS assay on BAL specimens should be ordered only after all other testing has failed to find the etiology but an infection is still suspected. “The ideal of one test being performed at the beginning to catch everything,” she said, “is not yet ready.”

Sherrie Rice is editor of CAP TODAY. Dr. Young’s collaborators were Kimberly Hanson, MD, MPH, Daniel Thomas, and Taylor Snow.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management