September 2020—Between a rock and a hard place. Trying to stay ahead, trying to build inventory. Chasing multiple new testing requests. Anticipating influenza.

That’s where laboratory leaders said their labs were in early August when CAP TODAY publisher Bob McGonnagle convened members of the Compass Group on Zoom to share their pandemic experiences. They shared surprise, too, that the situation is what it is: “Not a clue in my mind that this would go past the springtime,” said Stan Schofield, president of NorDx and senior VP, MaineHealth.

McGonnagle asked them about the diversion of supplies, the coming flu season, IT support, lessons and long-term changes, and more, including: “Why doesn’t pathology and laboratory medicine have a Dr. Fauci?”

On the call, in addition to Schofield, were Gregory Sossaman, MD, of Ochsner; Judy Lyzak, MD, MBA, of Alverno; Sterling Bennett, MD, MS, of Intermountain; James Crawford, MD, PhD, Mike Eller, and Dwayne Breining, MD, of Northwell; John Waugh of Henry Ford; Robert Carlson, MD, of NorDx; Pamela Murphy, APRN, PhD, of Medical University of South Carolina Health; Susan Fuhrman, MD, of OhioHealth; and Norman Gayle of Regional Medical Laboratory.

The Compass Group is an organization of not-for-profit IDN system lab leaders who collaborate to identify and share best practices and strategies. Here is what they told us.

Did you have any idea when you first began to understand the severity of the pandemic that we would still be in the same place on Aug. 4? One of the Compass Group members, Susan Fuhrman of OhioHealth, said, and I quote from a CAP TODAY story published in August, “It just keeps getting surprisingly worse.” Greg Sossaman, do you have a reaction to that? And would you in your wildest dreams have thought you would be up in the air on Aug. 4?

Gregory Sossaman, MD, system chairman and service line leader, pathology and laboratory medicine, Ochsner Health: I agree with Susan Fuhrman in her assessment. We continue to bring up and expand testing, but it just continues to be more complicated.

Schools are beginning to start here next week and that scares me. More literature is coming out about how children are not as protected as initially thought and that they can be very infectious, and yet nobody has a school testing program. We don’t have the capacity to test teachers and students every day like they should be tested.

We now have a decent handle on the patient testing we’re doing, but we struggle with community and employer testing. We are using every single test we have every day and continue to bring up more. I didn’t think it could get more complex, and I thought we would be back to a new abnormal by now.

Stan Schofield, did you have any idea we would still be in this boat on Aug. 4?

Stan Schofield, president, NorDx, and senior VP, MaineHealth: No. We had the assay ready to go in mid-February, a laboratory-developed test, and I had inventory and supplies for 6,000 patients. I thought I was wasting money. I thought this is overkill, like the swine flu of 10 years ago where you wind up eating a lot of reagents. We blew through that in three weeks and have been on a scavenger hunt since then—all day, every day—to get supplies and materials. Not a clue in my mind that this would go past the springtime. And as Greg Sossaman said, we have industry, corporations, universities. Everybody wants to get tested. And it’s hard to try to help the community in general because of the limitation in reagents, supplies, and equipment. We’re meeting the needs of the health care system—keeping it fairly COVID-free for elective surgeries and diagnostic procedures—but there’s not a lot left over after that to help the community in general.

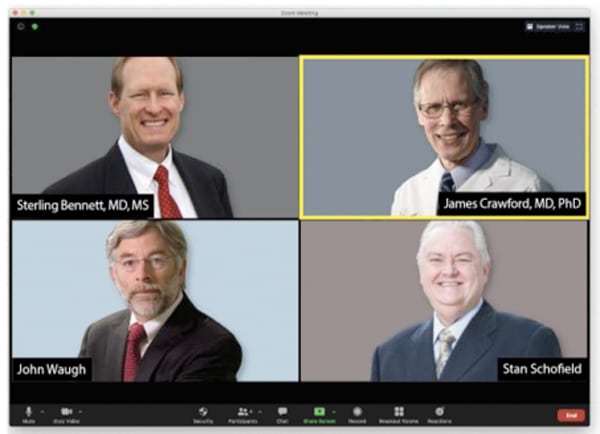

Members of the Compass Group, among them Dr. Bennett, Dr. Crawford, John Waugh, and Stan Schofield, met by Zoom in August to talk about where things stood for clinical laboratories. “This has been a sobering lesson in the fragility of our system,” Dr. Crawford said, noting it’s about more than pandemics, and adding, “As laboratory leaders, we have to be much more mindful of that fragility.”

So we’re kind of between a rock and a hard place. We’re going into a big service demand time period and there’s very little we can do to offer support or help.

There’s a lot of finger-pointing going on, and a lot of people seem to think reagents can be stamped out as if they were widgets. In terms of the industry being caught short, they can talk about producing reagents and the time it takes to do so. It’s more like brewing a great beer than it is stamping out a bunch of metal parts. Stan, can you talk about that?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): You’re correct. We were all geared up for a world of great efficiency and low-cost operations. Not a lot of excess capacity. And the diagnostic companies were tooled up and managed to meet those needs in a strong business environment with a lot of competition. They couldn’t have a lot of waste or a lot of development cost. And SARS-CoV-2, in moving so quickly, caught everyone flat-footed and stupid. It was on us before we knew what was happening. The government was slow to react. Most of these diagnostic companies are big ships; you can’t turn them around in the middle of the bay. And with a bridge and everything else to worry about for regulations, standards, and quality, they’ve done a pretty good job. It’s been compounded because now it’s global and all these companies are global companies. So it’s not just what we want, it’s what the world wants.

We could have done a better job and a few more things, but the government has gotten involved a lot with this. The redirection, redeployment of supplies has not gone well, and a lot of areas have been stranded. The government’s position is more or less, save the cities, let the countryside burn. And while the countryside is burning now, there’s not much to redeploy because the demand is growing, not only from a political standpoint but also from a community and public standpoint. We get requests every day. They’re not sick; they need a test so they can go back to college or elsewhere.

The diagnostic companies—fixed, well-established organizations that can’t easily expand—have had unprecedented demand. You can’t build giant molecular diagnostic manufacturing factories in 30 or 40 days. Giving them the benefit of the doubt, from what I’m hearing, most are expanding and working hard to do that.

Dr. Lyzak

Judy Lyzak, what’s going on at Alverno? Are you largely in agreement with what you’ve heard from your colleagues so far?

Judy Lyzak, MD, MBA, VP of medical affairs, Alverno Laboratories, Indiana and Illinois: Yes, we’re very much in the same boat. We’re doing okay on our core-laboratory–performed tests, but we’re encountering a real shortage with the rapid molecular test in the hospital—our Abbott ID Now. Thankfully, we’ve controlled the utilization of that test with strict algorithms and guidelines on how our physicians can use it and for what patients, so the impact of the allocation limitations has been minimized. But it’s still a little startling when you are used to practicing until this point in a land of plenty. It was a little startling, as it is to learn daily from a vendor, that an allocation you assumed was going to be delivered at a certain point that very day has been likely redirected to someone else. And then you have to have the unpleasant conversations in real time with your clinicians across a vast geography to tell them that now they have to practice in a world of limited resources and without a rapid test for use in the ED.

If the Compass Group members are having trouble getting adequate supplies for their testing needs, what is happening at the 100-bed hospital in rural Utah or western Nebraska or South Dakota? Your labs should be as well taken care of as anyone in the country, and yet I know you’re not. And I know from LabCorp and Quest that even their public statements about turnaround times are highly optimistic. So what, from your perspective, Sterling Bennett, is explaining some of this?

Sterling Bennett, MD, MS, medical director, Intermountain Healthcare central laboratory, Salt Lake City: The situation in the rural areas is variable. We were contacted by our Cepheid rep, who said they have been instructed to provide x number of rapid molecular tests to three rural hospitals, and they had a designated list. They were receiving instructions from somewhere out in the ether that these rural facilities needed to be given preferential treatment with a quota of tests that vastly exceeded the usage in their communities. But then we have other facilities that seem to have no access at all to testing supplies. So it seems to be highly variable. And I think the main underlying reason is that none of us has ever lived through this before, and we’re all making it up as we go. People in industry are making it up in a different way than people in government, who are making it up in a different way than the people in health care.

One of the themes that has emerged almost from the start has been a dissatisfaction with a national policy. That’s a discontent that seems to be constant even though it has morphed. At the start there was a limited algorithm for people to get these tests, and now it seems like the sky’s the limit, that everybody almost as a right needs to have their molecular PCR status of COVID known. And that’s what’s in part gumming up the system, and the test shortage will continue well into the flu season. Would anyone like to speak in favor of returning to a national algorithm for patient testing?

Dr. Breining

Dwayne Breining, MD, executive director, Northwell Health Laboratories, New York: It would be nice if there were a coherent strategy tying up all the loose ends, because having everybody competing against everybody else is not optimizing the situation.

I’m of a mixed mind about the national testing algorithm, because in terms of reopening the economy in the New York area, you do want to be able to swab as many people as you can. Basically every citizen of the New York area is at risk for exposure because it was so prominent here. And to identify patients and then isolate, you want to be able to do the swabs. At the same time, we don’t have nearly the capacity we wish we had. I’ve been in conversations with the governmental offices about possible alternative testing strategies for ongoing surveillance of institutions like schools, colleges, those types of things, where we can possibly bring antibody testing into the algorithm to do an ongoing surveillance of seroprevalence rates. But of course that would need to be accompanied by swab testing, at least in the initial phases and in some sort of ongoing sampling algorithm. So it’s preliminary at this point.

As for that small country hospital in the Dakotas or Utah that you brought up, if it doesn’t have cartridge-based testing—and I don’t think anyone has enough of that at this point—it has to send to the national commercial labs. Quest has been overwhelmed—we have had tests that have gone to Quest that are 18 days and still pending results. LabCorp, I think, is faring a little bit better. That’s because they’re charging more for the testing, so they diverted some of the demand. All of the national labs are telling the same story, and they are overwhelmed.

James Crawford, MD, PhD, professor and chair, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and senior VP of laboratory services, Northwell Health, New York: Regarding your prior question, you don’t have to be in South or North Dakota. Upstate New York is experiencing the same problem—the community hospitals don’t have the capacity.

My concern is that the solution might be worse than the problem. There’s discussion, at least at the New York State consortium level, about how nice it would be to have pathologists involved in these planning decisions, but that doorway has not opened up. Instead, it’s our health system CEOs who have the governor’s ear. Dr. Breining has his own back door to the governor’s council. Other states’ laboratories may have better channels to the policymakers. But the idea of people who have nothing to do with the lab industry coordinating national lab test supply is something we should be careful about recommending. I’d love to see national coordination, but I am not alone in saying it depends on who is in the room.

John Waugh, you’ve been observing this lab world for a long time, always with great insight. Why does the laboratory seem to be so shut out from some of the decisions that need to be made?

John Waugh, system VP, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit: Some of this is politics and some of it is science, as all of us know now. Unfortunately, the politics are happening; we’re in the middle of a political season. And that emphasizes a lot of the trigger points. But there is no question that at the federal level there is a big impact on moving around supplies. And the question was raised about where it’s coming from. It’s the White House Coronavirus Task Force. It’s Admiral Brett Giroir. I was on a conference call with him two weeks ago, and on that call he said, “I’m taking NIH money from Dr. [Francis] Collins here, and I’m going to buy consumable supplies from Hologic. And I’m going to move that to where I need it.” And he did the same with products from Abbott and Roche. So there are big, heavy hands moving these around.

And then he said—and I’m not judging whether it’s good or bad—what they want is the testing numbers to go up. Everything that was presented got approved as an EUA, so we had a lot of bad product out there, and now they’re trying to reel that back in. But going forward, his position is that we have to have more testing, we have to have cheaper testing, everybody doesn’t need PCR testing with its costs and time constraints, and we need to get down to testing at maybe $2 to $5. I can’t imagine what those kinds of tests are going to be or what the utility will be. But here’s somebody who doesn’t make his living in diagnostics—probably a great admiral, a great pediatric intensivist—but as assistant secretary for health in the Department of Health and Human Services he wields a lot of authority on how to move product around.

I’ve talked with company executives, even to the CEO level, who are cautious in not wanting to lose control of their supply chain. And the federal government has a spreadsheet it is keeping with 14, 15 company names on it of what’s being produced and where it is going. And these company executives have to make sure they’re moving product to the hot spots and underserved areas. Otherwise they’re going to lose control of their supply chain. And they want to take care of their own customers without having the federal government do it for them.

Robert Carlson, is a national algorithm, or a new algorithm for selecting patients to be tested, a little like trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube? Is the genie out of the bottle and we just have to deal with it?

Dr. Carlson

Robert Carlson, MD, medical director, NorDx, MaineHealth: I’m afraid you’re right. I call it boiling the ocean. There are so many different demands. A logical, systematic approach where the sickest or the ones who need the test the most get the test would be a good start. But the demand is so far outstripping the supply that it’s going to be difficult to even begin to think about rationing, other than what the government is doing.

To what degree are the various health care systems back to business as usual? Elective surgeries, school physicals, et cetera. Greg Sossaman, what’s going on at Ochsner?

Dr. Sossaman (Ochsner): We’ve mostly resumed—surgery and clinic visits are back. Some of it has changed a bit, but most of that volume has come back. We’re probably in a little better position than some of the other hospitals in the state with such things as ICU capacity. Overall as a system, we are doing very well compared with where we were in March and April, though we’re not where we wanted to be at this point compared with last year.

Is this returning volume also crimping your ability to generate the kind of COVID tests that are demanded of you within the system?

Dr. Sossaman

Dr. Sossaman (Ochsner): There’s definitely competition for resources. For a while we were pulling staffing from other areas to work in our molecular lab at night or in other areas. Yes, as volume has come back, those techs have gone back to those areas, so it’s been difficult to maintain staffing in our molecular areas.

Stan Schofield, how is the return of some normalcy affecting your ability to operate the laboratories?

Stan Schofield (MaineHealth): Surgeries are about 90 percent back to pre-COVID norms for the big hospitals. For the small hospitals, it’s about 70 percent. The ambulatory setting is at about 80 to 85 percent based on locale in the state and population density. We are approaching our capacity under social distancing and physical and scheduling limitations.

We’ve added multiple lab staff to molecular. I’ve asked for more people to be recruited. For the next 12 to 18 months, we’ll never have enough people. But we’re going to keep trying to stay ahead of the curve because of the demand, because reagents are going to catch up and we’re going to be okay. But then we’re going to have the preanalytic bottleneck, the specimen collection. And we’ve been buying and expanding testing capacity with instrumentation and automation. So we’re trying to stay ahead by adding preanalytic and molecular people at every opportunity.

We’ve expanded a lot, but it’s not enough. What I see is the demand going into the fall with the flu and COVID combination.

The COVID asymptomatic demands are increasing every day—presurgery, pre-diagnostic, MRI, CT scan, labor and delivery. Now medical students have to be tested weekly, and all of this is rolling in. The number of asymptomatic patients exceeds the number of our symptomatic patients by 30 percent on an average day.

It takes a lot of resources to keep the health care system a COVID-free zone, so people don’t stay away. And the data are impressive: 20,000 people pre-screened, 25 are positive. That works, and it’s good information. But then everybody says, okay, that’s what I’ve got to have. I don’t want rapid ID Now; I want molecular. It’s the gold standard; I can count on it. And anything less than that is not acceptable to the medical staff.

Sterling Bennett, what are your thoughts on this? As the system returns to something a bit more normal, it’s clear that puts even greater demands on the laboratory.

Dr. Bennett (Intermountain): It does. So we’ve seen essentially a rebound to baseline for our laboratory volumes and our anatomic pathology volumes. Not quite, but close. Initially, as others have described, we shuffled people to do COVID testing, and as the volumes rebounded we had to move them back out. So we’ve had to fish around the system and redeploy individuals from other areas to keep the COVID testing flowing.

Judy Lyzak, are all your surgical pathologists back at the scope?

Dr. Lyzak (Alverno): We are. Our volumes have rebounded to about 80 to 90 percent of where they were—some hospitals a little more than others. So, yes, we are clawing our way back. And we are experiencing many of the same problems that my colleagues on today’s call have spoken to. One of our limiting factors, in addition to the supply chain problems, is having enough staff to push these thousands of tests through every day and meet the physicians’ expectations on turnaround time. When we introduced the risk assessment for surgeries, they wanted those faster than anything, and then they complained we couldn’t get the risk assessments done as quickly as they wanted and take care of all the acute patients as well. So balancing all of that, and using the EMR technology to configure those orderables so we understand how to prioritize things in the laboratory, has been a real challenge.

We’re about to go into a flu season, and it would seem as though the demand is going to be exponentially raised to put this testing on some kind of a multiplex system that can do flu A and B plus COVID. Dwayne Breining, is that your assessment of what’s going to happen to us once the flu gets its first foothold on the system?

Dr. Breining (Northwell): That’s exactly right. If you look at especially the crowded urban hospital setting, in a normal flu season the hallways back up with patients waiting for flu results, even when we do have enough flu testing in the hospitals. You can imagine now the patient cohorting nightmare that’s going to occur because anyone coming in with flu-like symptoms is going to need to be tested for COVID and flu. We see a lot of RSV as well.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management