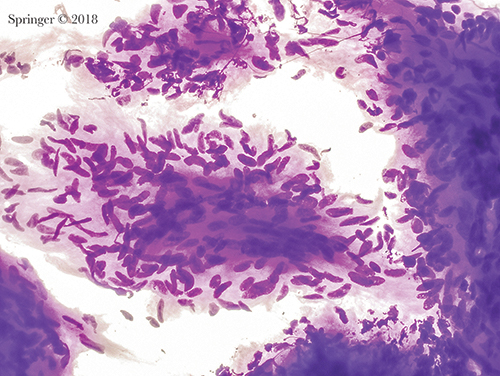

Neoplasm: benign. This aspirate of schwannoma shows a group of bland spindle cells with wispy cytoplasm. The cytoplasmic borders are indistinct. Nuclei are spindle-shaped and display bends or curves (smear, Romanowsky stain).

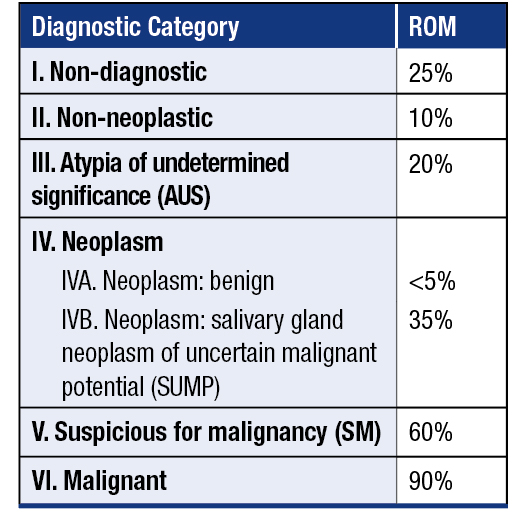

The non-neoplastic category includes benign, reactive, metaplastic, and inflammatory processes such as acute, chronic, and granulomatous sialadenitis. The risk of malignancy, or ROM, for this category will be low when strict inclusion criteria are used. It is recognized that sampling errors occur, and such errors can be responsible for a non-neoplastic diagnosis when a neoplastic lesion is present. Recommendations are made for close clinical follow-up and radiologic correlation.

Similar to the Bethesda System for thyroid cytopathology, the Milan System strictly defines and limits the FNA cases assigned to its atypical category, AUS (atypia of unknown significance). FNAs classified as AUS samples contain limited atypical features that are indeterminate for a neoplasm. According to Milan criteria and literature experience, AUS cases should account for less than 10 percent of salivary gland FNA samples. In this way, a goal of the AUS category is to reduce the number of false-negative diagnoses in the non-neoplastic category while helping to maintain the significance of the neoplastic category. Cases diagnosed as AUS could be managed by either repeat FNA or conservative surgical resection according to the specific clinical and radiologic contexts of the lesion.

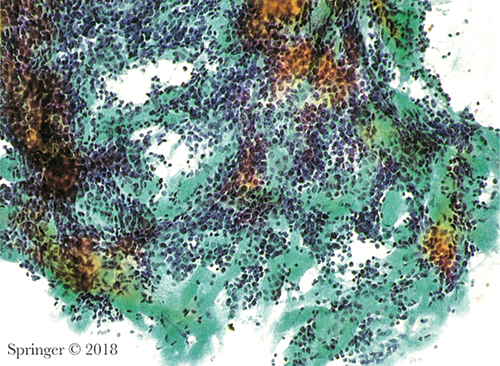

Suspicious for malignancy. This smear is composed of basaloid cells and abundant matrix spheres with a pattern suspicious for adenoid cystic carcinoma (smear, Papanicolaou stain).

There are two different subgroups of neoplasms in the Milan System. The first, termed “benign,” is reserved for cases of benign neoplasms diagnosed based on the presence of established cytomorphologic criteria including classical cases of pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumor. A number of other entities, such as benign soft tissue tumors including lipoma and schwannoma, are incorporated into this category. As expected, the ROM for this category should be low (less than five percent). Most benign salivary gland neoplasms such as pleomorphic adenoma are managed by conservative surgical resection, although in selected cases the patient might be followed clinically.

Malignant. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. Aspirates show small high N:C ratio basaloid tumor cells surrounding acellular matrix with a cribriform pattern (smear, Papanicolaou stain).

The second neoplastic group is defined as salivary gland neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential, or SUMP. It consists of FNA specimens that are diagnostic of a neoplasm but for which a diagnosis of a specific entity cannot be made and, importantly, a carcinoma cannot be entirely excluded. A majority of SUMP cases will be cytologically bland cellular neoplasms, neoplasms with atypical features, and low-grade carcinomas. Subsets of the different entities in the SUMP category are included based on basaloid, oncocytic, or clear cell features. Even though entities in the SUMP cytologic category may not have a precise classification, the category defines a ROM of approximately 35 percent and provides important information to help guide clinical management. In the majority of cases, lesions classified as SUMP will typically be managed by conservative surgical resection with negative margins. Currently available ancillary immunohistochemical and molecular studies may allow for more precise classification.

Acinic cell carcinoma. SOX10 immunostain showing strong nuclear expression in the tumor cells in a cell block.

In the suspicious for malignancy (SM) and malignant diagnostic categories, definitions and criteria are analogous to the same categories in other anatomic sites. Lesions classified as SM have features suggestive of malignancy but the sample is either deficient in the quality of the cellular features or the quantity of abnormal cells present. For salivary gland FNAs diagnosed as malignant, criteria are provided to enable cytologists to subclassify the tumors into low-grade and high-grade entities, since these designations have significant implications for patient management. Management of high-grade carcinomas may include radical surgical resection, sacrifice of major nerves, and neck dissection.

Diagnostic categories and risk of malignancy in The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology

The Milan System atlas chapter dedicated to ancillary studies details the use of ancillary techniques, including immunochemistry and molecular testing, and makes clear the role such ancillary tests can play in increasing the overall accuracy and effectiveness of salivary gland FNA.

Efforts are underway to encourage the cytology community to follow the Milan System on Twitter (https://twitter.com/MilanSystem) and Facebook (www.facebook.com/MilanSystem) or the ASC website (www.cytopathology.org) and the Milan System site (www.milansystem.org). There, the latest updates, case examples, and discussions related to salivary gland FNA will be found. The editors are conducting an interobserver reproducibility study with access available through the ASC website. In addition to the print atlas, a Web atlas of the Milan System illustrating numerous examples from each of the diagnostic categories will also be available through the ASC website in the coming months.

- Faquin WC, Rossi ED, eds. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018.

- Ahn S, Kim Y, Oh YL. Fine needle aspiration cytology of benign salivary gland tumors with myoepithelial cell participation: an institutional experience of 575 cases. Acta Cytol. 2013;57(6):567–574.

- Al-Abbadi MA. Pitfalls in salivary gland fine-needle aspiration cytology (author reply). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1428.

- Ameli F, Baharoom A, Md Isa N, Noor Akmal S. Diagnostic challenges in fine needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions. Malays J Pathol. 2015;37(1):11–18.

- Chakrabarti S, Bera M, Bhattacharya PK, et al. Study of salivary gland lesions with fine needle aspiration cytology and histopathology along with immunohistochemistry. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108(12):833–836.

- Colella G, Cannavale R, Flamminio F, Foschini MP. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(9):2146–2153.

- Kim BY, Hyeon J, Ryu G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology for high-grade salivary gland tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(7):2380–2387.

- Krane JF, Faquin WC. Salivary Gland. In: Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, eds. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Griffith CC, Pai RK, Schneider F, et al. Salivary gland tumor fine-needle aspiration cytology: a proposal for a risk stratification classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(6):839–853.

- Rossi ED, Wong LQ, Bizzarro T, et al. The impact of FNAC in the management of salivary gland lesions: institutional experiences leading to a risk-based classification scheme. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124(6):388–396.

- Schmidt RL, Hall BJ, Layfield LJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy for salivary gland lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(4):516–526.

- van der Schroeff MP, Terhaard CH, Wieringa MH, Datema FR, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. Cytology and histology have limited added value in prognostic models for salivary gland carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(9):662–666.

- Wang H, Fundakowski C, Khurana JS, Jhala N. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of salivary gland lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(12):1491–1497.

- The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology, 2nd ed. Ali S, Cibas ES, eds. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

- Rossi ED, Faquin WC, Baloch Z, et al. The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology: analysis and suggestions of initial survey. Cancer Cytopathol. 2017;125(10):757–766.

Dr. Rossi is in the Division of Anatomic Pathology and Histology, Catholic University of Sacred Heart, and a professor in the Agostino Gemelli School of Medicine, Rome. Dr. Kurtycz is medical director, Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, and a professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison. Dr. Faquin is director of head and neck pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and professor of pathology, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Drs. Rossi and Faquin are editors, and Dr. Kurtycz is an associate editor, of The Milan System for Reporting Salivary Gland Cytopathology.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management