Charna Albert

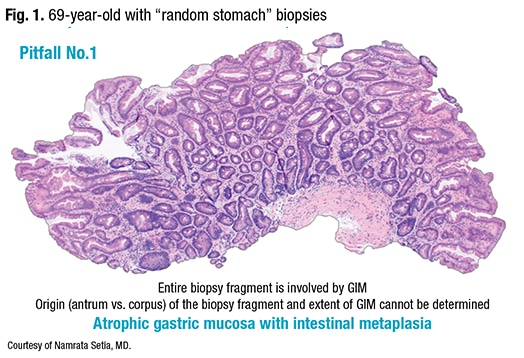

February 2022—How to classify gastric intestinal metaplasia, when to classify it, and the implications of a GIM diagnosis were the focus of a CAP21 presentation in a session on advances in gastric neoplasms.

The big question, said presenter Namrata Setia, MD, associate professor of pathology, University of Chicago School of Medicine, is, “Why are we suddenly talking about classifying intestinal metaplasia in the stomach? I haven’t gotten a call about this topic until recently.” The reason, she said, is in 2020, the American Gastroenterological Association published the first U.S.-based clinical practice guidelines on the management of GIM (Gupta S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158[3]:693–702).

According to the literature, among patients with GIM who had biopsies taken from both the gastric antrum/incisura and body, extensive GIM versus limited involvement (involvement of at least the gastric body versus GIM of the antrum and/or incisura, respectively) was associated with a twofold higher pooled relative risk of incident gastric cancer (RR, 2.07; 95 percent CI: 0.97– 4.42). Having incomplete versus complete GIM was associated with a threefold increased risk for incident gastric cancer on follow-up (RR, 3.33; 95 percent CI: 1.96 –5.64), and having a family history of a first-degree relative with gastric cancer was associated with a 4.5-fold increased risk for gastric cancer among patients with GIM (RR, 4.53; 95 percent CI: 1.33 –15.46).

But notably, Dr. Setia said, “none of the studies used to calculate the provided relative risks were from the United States, indicating the lack of data from the United States. So the guidelines’ coauthors published another paper in the same edition of Gastroenterology urging pathologists to classify intestinal metaplasia, and hence the recent uptick in classification requests” (Shah SC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158[3]:745 –750). In their guidelines, Gupta, et al., write, “Anecdotally, U.S. pathologists rarely report presence of incomplete vs complete GIM as part of routine GIM diagnosis,” which “raises concerns as to whether the histologic subtype of GIM can be feasibly utilized as part of risk stratification in the United States without a substantial educational initiative for pathologists.”

Helicobacter pylori-associated GIM, Dr. Setia said, originates at the incisura, involves the antrum, and then spreads to the corpus. “But it doesn’t have to involve the entire antrum before extending to the corpus.” Thus, to classify GIM histologically, the extent, or number of sites involved in the stomach, and the grade, or severity of GIM involvement of the biopsied fragments, should both be measured. The subtype, an additional histologic classification for GIM, is based on distinct microscopic appearances. “For the purpose of using intestinal metaplasia to identify high-risk individuals, the AGA guidelines recommend using the extent and subtype.”

In determining whether the extent of GIM is limited or extensive, the antrum and incisura are considered one site; the corpus, including the body mucosa, is considered another site. The European guidelines (published in 2012 and revised in 2019) classify GIM as limited if one site—antrum/incisura or corpus—is involved, and as extensive if both sites are involved (Pimentel-Nunes P, et al. Endoscopy. 2019;51[4]:365 –388). The AGA takes a different approach. GIM is considered limited if the antrum/incisura alone is involved. “But as soon as you see intestinal metaplasia in the corpus, even if you don’t see it in the biopsies from the antrum/incisura, it’s classified as extensive,” Dr. Setia said. “And their rationale is intestinal metaplasia may not form a visible lesion and can easily be missed in endoscopy.” So intestinal metaplasia seen only in the body but not in the antrum, according to the AGA guidelines, doesn’t mean it’s absent, she said. “They presume it was there but not sampled.”

Dr. Setia presented two sets of gastric corpus and antral biopsies: one obtained from a 66-year-old, in which GIM could be seen in the corpus and in the antrum at multiple foci, and one from a 72-year-old, in which GIM could be seen in the corpus but not the antrum. The former would be considered extensive by both the AGA and European guidelines (known as MAPSII), she said, as both sites are involved. But the latter would be considered limited by the MAPSII guidelines and extensive by the AGA guidelines. For the AGA, the absence of GIM in the antral biopsies could indicate it was present but not sampled. “The other possibility is the patient may have autoimmune gastritis,” she noted. The MAPSII guidelines recommend performing an endoscopy every three to five years to surveil patients with autoimmune gastritis. But the AGA guidelines do not make recommendations regarding autoimmune gastritis, she said, because of the lack of definitive evidence or data from the U.S. supporting surveillance.

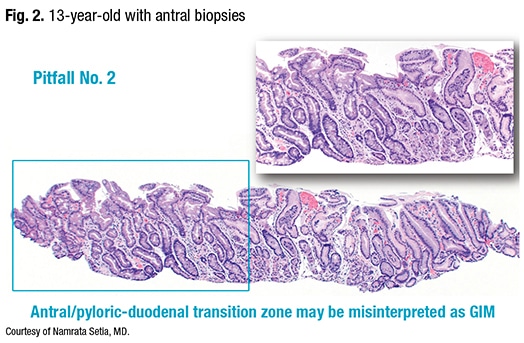

The second pitfall: the antral/pyloric-duodenal transition zone may be misinterpreted as GIM. In antral biopsies obtained from a 13-year-old (Fig. 2), “we see the zone of intestinal glands,” Dr. Setia said, “but otherwise this child had pristine GI biopsies, so these glands clearly represent the pyloric-duodenal junction. The point from this case is one has to be careful not to misinterpret the pyloric-duodenal junction as antral intestinal metaplasia.”

Although the AGA does not recommend using the grade to determine GIM’s risk of progression, Dr. Setia said, grading may be used in routine practice. In grading, each biopsy fragment is given an estimated decile score for percentage involvement by GIM, and subsequently, each site is given an average score for percentage involvement. “It is then classified as mild GIM if the percentage is between one and 30 percent, moderate if it is between 31 and 60 percent, and severe if it is more than 60.” But, she said, there’s a bit of confusion on this: “I’ve seen the term ‘focal intestinal metaplasia’ used for mild GIM, and ‘extensive’ used for severe.” She admits “extensive” sounds better than “severe” intestinal metaplasia, but according to the AGA guidelines, the term extensive should be used only for extent, not severity.

GIM subtyping, Dr. Setia said, can be performed on H&E slides, by using special stains (high-iron diamine), or with mucin IHC stains. H&E subtyping classifies GIM as complete or incomplete: “If you’re able to see the brush border and Paneth cells in the small intestinal mucosa, then the intestinal metaplasia is complete,” Dr. Setia said. “But if the intestinal metaplasia does not have a brush border or Paneth cells, it is incomplete.” The incomplete type, she said, has a distinctive hybrid epithelium, with goblet cells interspersed within the gastric foveolar cells (Fig. 3).

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management