Charna Albert

February 2023—Traditional algorithm? Or reverse? Elitza Theel, PhD, D(ABMM), of Mayo Clinic, in an AACC session last year walked through the two primary diagnostic algorithms for syphilis, explaining where the complexities lie and how her laboratory uncovered inappropriate testing for neurosyphilis.

Syphilis cases are up in the past decade, and by 11 percent between 2018 and 2020 alone, said Dr. Theel, director of the infectious diseases serology laboratory at Mayo Clinic and Mayo Clinic Laboratories. In women, the increase is 30 percent, and more than 50 percent of all U.S. counties reported cases in women of reproductive age, according to a 2020 CDC report. The CDC reported an increase in congenital syphilis rates of 425 percent between 2012 and 2020, leading to a more than 600 percent increase in syphilis-related deaths in neonates and infants.

“Every time I think about that I get goosebumps because this is a preventable disease,” said Dr. Theel, who also co-directs the vector-borne pathogens service line and is a professor of laboratory medicine and pathology, Mayo Clinic. “It’s important given this rise in cases to make sure we are on top of our game when it comes to syphilis diagnostics.”

Syphilis cannot be cultured on routine media, Dr. Theel said. And molecular assays are not readily available and have limited sensitivity, depending on stage of infection and the specimen tested. “Histopathology is available and helpful in some situations but remains imperfect,” she said, because of the limited sensitivity and specificity of the stains. “So that leaves serology, and decades later we still rely on treponemal and non-treponemal assays to diagnose syphilis.”

The Food and Drug Administration has approved 13 automated and three manual treponemal assays, with the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) assay considered the reference method. The non-treponemal assays are the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) tests. “And we rely on a combination of these,” Dr. Theel said, referring to treponemal and non-treponemal assays, “because their performance characteristics are imperfect when used alone.”

Dr. Theel

The non-treponemal assays have low sensitivity in primary syphilis and in the latent and tertiary stages. VDRL sensitivity is 62.5 to 78.4 percent in primary syphilis and 64 percent in late latent disease, and RPR sensitivity is 62.5 to 76.1 percent in the primary stage and 61 percent in late latent disease (Tuddenham S, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71[suppl 1]:S21–S42). “The other important thing to remember is that RPR titers will decrease and decline even in the absence of treatment, but they will also decline during treatment,” she said. “So they’re used to monitor response to therapy, with most patients seroreverting to negative anywhere from 16 to 18 months after initiation of treatment.” About 30 percent of patients will remain seropositive at a low level, however, “and the clinical significance of that remains unclear.”

Dr. Theel is often asked if syphilis can be missed due to prozoning of the RPR. In one study of more than 2,000 cases of syphilis, she said, less than one percent of RPRs were falsely negative due to prozoning (Liu LL, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59[3]:384–389). “And in my 10 years as a lab director, I have yet to see us miss a case of syphilis due to RPR prozoning. So this is very rare. What’s not rare, though, are false-positive RPRs,” she said. False-positives are seen in less than two percent of samples, often in older individuals, and in those with recent vaccinations, in pregnant patients, in those with HIV, malaria, leprosy, and Yaws, as well as among patients with certain autoimmune diseases.

The treponemal assays have a significantly higher sensitivity in the primary and late latent stages, with the TP-PA at 86.2 to 100 percent sensitivity in primary syphilis and the enzyme immunoassays, chemiluminescence immunoassays, and multiplex flow immunoassays at 91.7 to 98.5 percent sensitivity in late latent disease, for example (Park IU, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71[suppl 1]:S13–S20; Loeffelholz MJ, et al. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50[1]:2–6). “But they suffer from false-positives, primarily due to Epstein-Barr virus infections, Lyme disease, and select autoimmune diseases,” Dr. Theel said. And more than 90 percent of patients will remain seropositive for life, “so we can’t use treponemal assays to monitor response to therapy.”

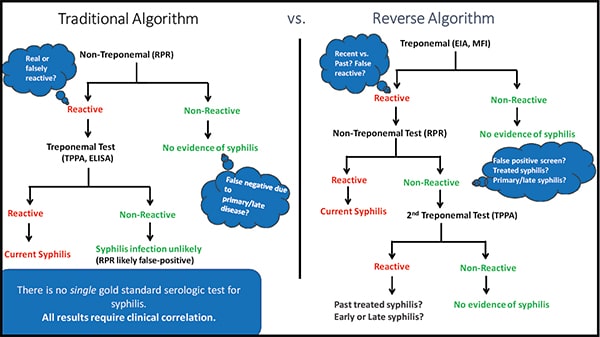

The traditional diagnostic algorithm for syphilis begins with an RPR (Fig. 1). “If that’s nonreactive, that would suggest no evidence of syphilis,” she said, “but what we need to be thinking at this point is, could this be a false-negative due to primary or late latent syphilis?’’ If it’s reactive, “we’ve got to think, is this real or could this be a false-positive result?” The next step is a treponemal test. “If that’s nonreactive we would consider this an unlikely syphilis infection, with the RPR potentially a false-positive result. Whereas if we have two reactives, then you have a syphilitic patient and you’re done.”The reverse algorithm begins with a treponemal immunoassay. “If it’s nonreactive, you can be fairly confident your patient does not have syphilis, unless exposure occurred super recently. But if it’s reactive, you’ve got to think, is this a recent infection, or could it be a past infection that has been treated, or is this a falsely reactive result?”

Fig. 1

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management