The quantitative defects affect the amount of alpha- or beta-chain produced. “That can lead to just a small reduction in one of those two chains, or it can lead to a complete absence of one of the globin chains,” Dr. Rhea-McManus said. “The thalassemia syndromes fall into this bucket.” And it’s possible to have both structural and quantitative defects in hemoglobin, known as a compound heterozygous variant. “For example, a hemoglobin S/beta thalassemia patient has a structural defect with their hemoglobin S, and they also have a quantitative defect with beta thalassemia.”

Average RBC lifespan, she said, is decreased in patients with the common Hb variants. In those with sickle cell trait (HbAS), for example, average RBC lifespan is 93 days, and it’s 87 days in those with HbC trait. RBC lifespan in those with HbD trait is closer to normal, at 115 days. And for HbE, “there’s not enough data to know if there is an impact on red blood cell lifespan and if so what that magnitude is,” she said.

Though assay manufacturers have been successful at eliminating HbA1c analytical interferences from the most common variants, there are hundreds of other variants, she said. “It’s possible that if you’re using a method where you can’t see a hemoglobin variant, it may interfere with that assay.” There are also mutations at glycation sites. “The glycation rate needs to be directly proportional to the amount of glucose present.” So a mutation that affects how quickly or slowly the molecule is glycated also can change the relationship between HbA1c and the glucose values it’s supposed to represent, she said.

In patients with the homozygous forms of HbS, HbC, HbD, and HbE, which cause the sickling of red blood cells, red blood cell lifespan is reduced even further. In sickle cell disease (HbSS), for example, average RBC lifespan is just 10 to 20 days. “So what is the impact?” she asked. “Often it may just be a percent change to hemoglobin A1c.” That percent, however, has a considerable effect on average blood glucose values. A six percent HbA1c, for example, represents 126 mg/dL in average blood glucose. In contrast, an HbA1c of seven percent represents 154 mg/dL, and an eight percent HbA1c represents 183 mg/dL.

“So seemingly small differences could have significant implications for a diabetic patient,” she said.

The American Diabetes Association recommends that plasma blood glucose criteria, rather than HbA1c, be used to diagnose diabetes in patients with conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover. And the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases says that physicians should not use the A1c test for patients with disease conditions such as HbSS, HbCC, or HbSC, she said, “noting that these values may not accurately represent the glycemic control of a patient.”

Dr. Rhea-McManus shared the case of a 36-year-old female of Sicilian descent with a history of obesity and hypertension. “She complained to her primary care physician that she was tired and often waking up at night to urinate.” At her appointment, her fasting glucose was 124 mg/dL—below the 126 mg/dL diagnostic threshold for diabetes. Her HbA1c, measured by immunoassay on two occasions, was 5.3 percent and 5.1 percent. Her physician assured her that she didn’t have diabetes and asked her to follow up in three months.The patient then relocated to a different state and saw a new physician for an exam (four months after the prior appointment), during which her fasting glucose was 142 mg/dL. A subsequent two-hour oral glucose tolerance test was 220 mg/dL, “with 200 being the threshold for diagnosis with diabetes.” At this appointment, the patient’s HbA1c, performed by ion-exchange HPLC, was 16.7 percent. A note was appended to the lab report indicating that a presumptive hemoglobin variant was suspected.

Subsequent laboratory testing and investigation by the patient’s physician revealed the presence of HbS/beta thalassemia (Rhea JM, et al. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141[1]:5–16). “So using a method where you can’t identify or know that the patient has a hemoglobin variant could lead to delayed diabetes diagnosis, as in this case,” she said.

In another case, a 36-year-old Japanese male presented to the hospital with stroke. Though his fasting glucose was normal, at 120 mg/dL, his HbA1c was 10.1 percent, measured by immunoassay. “So he was started on medications to try to reduce that A1c value,” Dr. Rhea-McManus said. When he followed up with his physician, his fasting glucose was 73 mg/dL. “He had been tracking his home blood glucose levels and his logs showed that he was in good glycemic control, but his hemoglobin A1c was still 10 percent.” For the next several years the patient underwent adjustments to his medication, though he insisted his glucose logs were accurate and that he was compliant with his physician’s recommendations. After a couple of episodes of hypoglycemia, he was referred to a specialist. When his HbA1c was tested by HPLC it was 5.4 percent, and a note appended to the lab report indicated the presence of an abnormal peak. Subsequently he was found to have Hb Himeji, a rare and clinically silent Hb variant (Shimizu S, et al. J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 2015;58[2]:121–127).

“So in this case,” she said, “using a method in which there was no indication to the physician that there was a hemoglobin variant present led to the misdiagnosis of diabetes and two years of unnecessary treatment. After this finding he was removed from those medications and monitored, and his glucose stayed well within the normal ranges.”

In one study of 500 HbA1c samples submitted for testing in two hospitals, the authors determined the prevalence of HbSS (2.2 percent), HbSC (1.2 percent), and HbS/beta thalassemia (one percent) and estimated the number of samples for which a misleading HbA1c result would have been reported if assays unable to detect Hb variants were used. In 2011, for example, the total volume of HbA1c tested was 72,333 samples. Thus, an estimated 1,591 samples would contain HbSS, 868 would contain HbSC, and 723 would contain HbS/beta thalassemia (Rhea JM, et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137[12]:1788–1791). “These are just numbers that indicate the potential for reporting a clinically misleading hemoglobin A1c number,” Dr. Rhea-McManus said.

There needs to be good and open communication between the laboratory and the treating physicians, she said. “If the physician sees something that doesn’t make sense, they shouldn’t take the A1c value at face value—we should be able to have those conversations about what might be happening. And the lab can also help guide what the additional investigation should look like.”

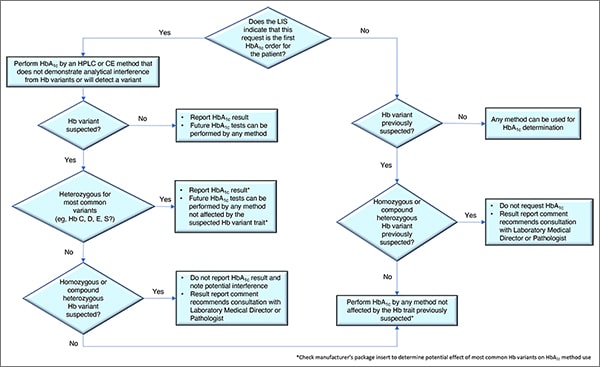

In Fig. 1 is a laboratory algorithm for HbA1c testing developed by Drs. Koch and Rhea-McManus and Lucia Berte. It begins with a question: Does the laboratory information system indicate this is the first HbA1c order for this patient? If yes, the test should be performed by an HPLC or capillary electrophoresis method that does not demonstrate analytical interference from the Hb variants or that can presumptively detect a Hb variant. If no presumptive Hb variant is suspected, the result can be reported and future tests can be performed by any method, Dr. Koch said. If a variant is suspected, and it’s identified as heterozygous for one of the most common variants, “we can report the hemoglobin A1c result,” but future tests should be performed using only methods not affected by the Hb variant trait. “Check the manufacturer’s package insert,” he said. “That will tell you whether or not they’ve identified these variants as being a factor to worry about.”If no common variants are found, in some cases a homozygous or compound heterozygous Hb variant may be suspected. “If so, we should not report the hemoglobin A1c result,” he said, and a potential interference should be noted. Consultation by the provider with the laboratory medical director or a pathologist also is recommended.

If the request is not the patient’s first HbA1c order, “then we should know whether or not a hemoglobin variant has been previously suspected,” he said. If no variant has been suspected, any method can be used. If a variant was previously suspected and it’s thought to be heterozygous for one of the most common variants, any method not affected by the common heterozygous variants can be used. But if a variant was previously suspected, and it’s thought to be a homozygous or compound heterozygous variant, the requested result should not be reported and the report should recommend that a consultation take place with the laboratory medical director or pathologist.

If the LIS isn’t capable of identifying the patient’s past HbA1c result and whether a hemoglobin variant was present, it may be necessary to set up a prompt at the point of order to query the system for that information. This would involve coordinating with the IT department, “which is often challenging,” Dr. Koch said. “But it needs to be done.”

Charna Albert is CAP TODAY associate contributing editor.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management