Charna Albert

April 2022—Don’t be afraid of livers.

Maryam K. Pezhouh, MD, offered that advice in a CAP21 presentation on autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and overlap syndrome, part of a session on common queries in liver pathology. “You don’t need to know everything when you’re looking at the liver,” said Dr. Pezhouh, associate clinical professor of pathology at the University of California, San Diego. “But you need to know what your clinician and your patient are asking.”

The main question: What is the major pattern of injury? Next is the degree of activity—is it mild, moderate, or severe? Sometimes a grade is assigned to the degree of activity, but Dr. Pezhouh prefers to be descriptive, “because a number is an absolute, and sometimes it won’t show the actual pathologies happening. For example, you have mild steatosis, but you have moderate inflammation around it. If I use different adjectives,” she explained, “I can tell them what I’m seeing.” The third question is the degree of fibrosis. Is it fibrosed yet, and if so, how much?

At the end of the report “I put everything together,” she said. “I say, I see this on the scope, and this is what you tell me the patient has, and I put two and two together and come up with a differential diagnosis.”

“Sometimes you are lucky,” in that what it is is clear, “but most of the time, especially in the liver, I’m not that lucky. I can narrow it down and tell them the pattern is hepatitic, or the pattern is in the bile ducts, or it’s cholestatic, and the differential diagnoses are different in each category.”

When Dr. Pezhouh receives a liver biopsy, she first examines the tissue at low power to look for the major pattern of injury, then at high power, after which she identifies the predominant morphologic pattern of injury. Next, she turns to the patient history to correlate her findings with the clinical information, and she calls the hepatologist to discuss the patient if necessary. “When I have all the clinical information, I go back to the slides to reevaluate and reach my final determination of the possible etiologies that can cause this pattern of injury.”

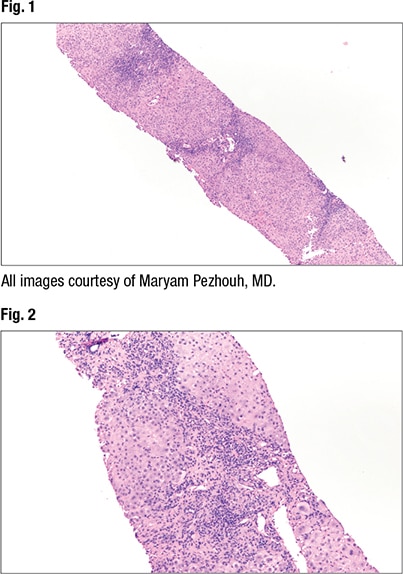

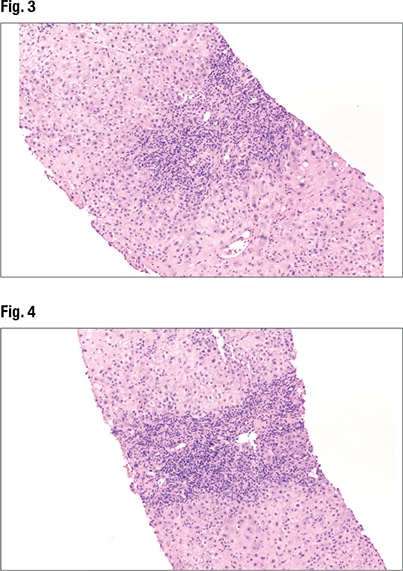

At low power (2× and 4×) the predominant histopathologic pattern of injury can be identified, Dr. Pezhouh said. “Is it fatty, is the inflammation portal, lobular, is it both? Is there necrosis, is there ischemia, is there sinusoidal dilation?” On low power, she said, “I think of different categories for diseases that can involve the liver.” And then at 10× or higher power she looks for specific clues, such as the type of fat (macro- or microvesicular, or evidence of steatohepatitis) and type of inflammatory cells. She also looks for other clues—Mallory bodies, apoptosis, single cell hepatocyte necrosis, and ischemia, for example. “Is there something that doesn’t belong there?”

At low power (2× and 4×) the predominant histopathologic pattern of injury can be identified, Dr. Pezhouh said. “Is it fatty, is the inflammation portal, lobular, is it both? Is there necrosis, is there ischemia, is there sinusoidal dilation?” On low power, she said, “I think of different categories for diseases that can involve the liver.” And then at 10× or higher power she looks for specific clues, such as the type of fat (macro- or microvesicular, or evidence of steatohepatitis) and type of inflammatory cells. She also looks for other clues—Mallory bodies, apoptosis, single cell hepatocyte necrosis, and ischemia, for example. “Is there something that doesn’t belong there?”

In her report, she describes the most prominent pathologic finding first. If the main finding is a fatty liver, for instance, “that should be your first line. And then you start describing everything else,” such as the portal tracts pathology, lobular pathology, and special stains performed, followed by a summary of the findings with the clinical and laboratory correlation. “Put everything together. Don’t just say, ‘This is chronic liver inflammation.’ Your hepatologist wants a differential diagnosis.”

For a specimen to be considered adequate, six to eight complete portal tracts are needed. To stage or grade chronic hepatitis, the specimen should be no less than 20 to 25 mm long, with at least 11 complete portal tracts. If the specimen isn’t adequate, Dr. Pezhouh reports that, since it can limit her ability to determine the cause of liver injury or amount of fibrosis.

The most common patterns of liver injury, she said, are fatty liver disease, hepatitic (acute, chronic, or acute on chronic), chronic biliary/cholestatic, giant cell hepatitis, necrosis/ischemia, and vascular disease. “And you can have a combined pattern,” she noted.

The most common patterns of liver injury, she said, are fatty liver disease, hepatitic (acute, chronic, or acute on chronic), chronic biliary/cholestatic, giant cell hepatitis, necrosis/ischemia, and vascular disease. “And you can have a combined pattern,” she noted.

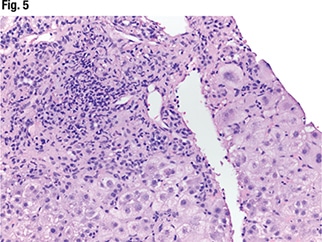

Under higher power (Fig. 3), interface hepatitis—in which inflammation enters the lobules—can be seen, as can inflammation in the portal tracts. In Fig. 4 (center), “there’s some spillage of the inflammation in the lobules but it’s mainly staying in the portal tracts at this point.” Under higher power (Fig. 5), “there are tons of plasma cells,” and lymphocytes are seen in the hepatocytes. “It’s somewhat rosetting the hepatocytes” (mid-left, bottom). “So there’s inflammation in the portal tracts, it’s spilling out tons of plasma cells, and there’s a selection of them going into the lobules and encasing the hepatocytes.”

The patient in this case is a 42-year-old female with a past medical history of ulcerative colitis who presented with dark urine and abdominal pain. With any case of ulcerative colitis, Dr. Pezhouh said, “you need to think about primary sclerosing cholangitis. But not every person who has ulcerative colitis has PSC.” The AST was highly elevated (967); ALT was 1524. Alkaline phosphatase was barely elevated (152), and bilirubin was normal (3.4). Antinuclear antibody was highly elevated (1:1280). Anti-smooth muscle antibody was negative. Ferritin was elevated (1780), and IgG was twice the normal level (2020). Ceruloplasmin was normal and the viral serologies negative.

“So at this point, based on everything, I favor autoimmune hepatitis,” Dr. Pezhouh said. “You have IgG elevation, you have positive autoimmune markers.” It’s more likely to be autoimmune than viral or a drug reaction at this point, she said, due to a constellation of findings.

In cases of autoimmune hepatitis, AST and ALT are often more than twice the upper limit, as seen in this patient. GGT and alkaline phosphatase usually are less than twice the upper limit, “and the same was true in our case,” she said, with elevated AST/ALT the most predominant finding. Of the autoantibodies, “in our case only ANA was elevated, but most often”—in 50 percent of cases—“you have both ANA and anti-smooth muscle antibody elevation” (ANA elevation alone, 10 percent of cases; ASMA elevation alone, 30 percent). LKM and LC1 elevation (liver/kidney microsomal and liver cytosol antibody) occurs in some cases (five percent), “and it’s usually type two autoimmune.” IgG is often more than twice the upper limit.

In cases of autoimmune hepatitis, AST and ALT are often more than twice the upper limit, as seen in this patient. GGT and alkaline phosphatase usually are less than twice the upper limit, “and the same was true in our case,” she said, with elevated AST/ALT the most predominant finding. Of the autoantibodies, “in our case only ANA was elevated, but most often”—in 50 percent of cases—“you have both ANA and anti-smooth muscle antibody elevation” (ANA elevation alone, 10 percent of cases; ASMA elevation alone, 30 percent). LKM and LC1 elevation (liver/kidney microsomal and liver cytosol antibody) occurs in some cases (five percent), “and it’s usually type two autoimmune.” IgG is often more than twice the upper limit.

A range of patterns is seen in autoimmune hepatitis, including fulminant and acute and chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis. “In fulminant hepatitis you see lots of necrosis and ischemia,” Dr. Pezhouh noted. But the main histologic features of autoimmune hepatitis are plasma cell rich portal tract inflammation, interface activity, and lobular inflammation (regenerative rosettes, emperipolesis). And as always, “you have to have compatible laboratory and histologic findings,” and other causes must be excluded. “If I see only plasma cells,” she said, “I’m not going to call it autoimmune.”

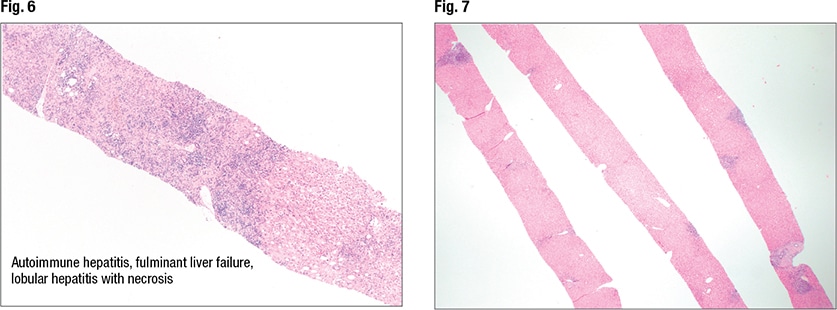

In Fig. 6 is autoimmune hepatitis with fulminant liver failure and areas of necrosis (left side of liver core). In such cases she notes the percentage of necrosis. “And I correlate with the laboratory findings.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management