Karen Titus

February 2020—Human endeavors are bursting with unintended consequences. Kudzu comes to mind. Smokestacks. Some even point fingers at Smokey Bear.

John Greden, MD, offers an example of his own, one with renewed relevance in pharmacogenomics. It’s a subject he’s studied closely, including as principal investigator of the GUIDED trial (Greden JF, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;111:59–67). Researchers looked at whether offering clinicians access to a pharmacogenomics test report would improve treatment for more than 1,100 patients with a major depressive disorder who had already failed to respond to an average of 3.5 antidepressant trials.

Philip Empey, PharmD, PhD, with Annerose Berndt, DVM, PhD, director of the UPMC Genome Center. “If the data’s available,” Dr. Empey says of pharmacogenomics, “I’m definitely on the we-should-be-using-it side of things.” (Photo: Scott Goldsmith)

Physicians with lengthy memories should find nothing revolutionary about using laboratory testing in mental health, says Dr. Greden, the Rachel Upjohn professor of psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, Department of Psychiatry, and founder and executive director, University of Michigan Depression Center. In the era of tricyclic antidepressants, physicians monitored plasma levels in patients fairly routinely. Says Dr. Greden, who chaired Michigan’s Department of Psychiatry from 1985 to 2007, “There was evidence early on that if you didn’t have an adequate plasma level, people did not improve.” Too high a level, moreover, was dangerous for patients who were poor metabolizers.

The pages began to turn with the publication of Prozac Nation in 1994, which helped popularize fluoxetine and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, Dr. Greden recalls. SSRIs are effective and don’t have the same risks—cardiac problems, orthostatic hypertension, etc.—that accompanied overly high levels of tricyclics.

But with that came an uncoupling of lab testing and depression treatment that, in retrospect, seems a bit unfortunate, Dr. Greden says. “There were some real clinical advantages in measuring plasma levels,” he says. In achieving safety and comparable efficacy—goals no one would argue with, of course—medicine may have derailed early momentum toward precision medicine.

“Now it’s going to take some work to get the mental health delivery system, at least, to start thinking along the lines of, What lab tests should I consider before I even make my drug choice?” says Dr. Greden, who is also founding chair, National Network of Depression Centers, and research professor at Michigan’s Molecular and Behavioral Neuroscience Institute.

But it’s work worth doing, he and others say, whether that means stepping forward or finding a way back.

Not every clinical condition lugs the same historical baggage when it comes to pharmacogenomics. Philip Empey, PharmD, PhD, associate professor, University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy and Therapeutics, says, “I see more and more academic institutions starting to initiate larger, broader projects to guide us in therapy. Notwithstanding reimbursement issues—those are real—to overcome those issues, the best thing we can do is generate real-world data of clinical utility.”

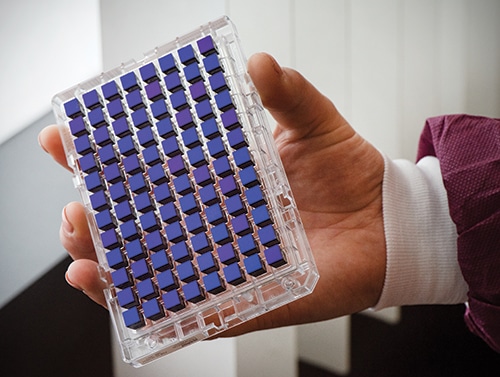

Each assay on the Thermo Fisher PharmacoScan array can test more than 4,600 markers in nearly 1,200 genes for a single sample, including copy number for targeted genes. The plate allows for testing of up to 96 patients simultaneously. (Photo: Scott Goldsmith)

His institution continues to charge ahead, building on earlier work. In 2015, Pitt/UPMC began a clinical implementation program focused on the role of CYP2C19 in clopidogrel (patients who are classified as CYP2C19 intermediate or poor metabolizers are unlikely to benefit from the antiplatelet drug), with about 3,000 patients assessed so far. Dr. Empey, who is also associate director of the Pitt/UPMC Institute for Precision Medicine, makes a rosy report: “That’s worked well, with strong payer reimbursement and great feedback from clinicians and patients.” Dr. Empey spoke about their work and PGx testing at the Association for Molecular Pathology annual meeting in November.

More recently, Dr. Empey and colleagues are deploying, through Pitt’s newly established Pharmacogenomics Center of Excellence (of which he is director) and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute, preemptive population-based screening as a part of a Pitt/UPMC research study.

This is a large biobanking project, called Pitt+Me Discovery. Enrollees have the option to receive their pharmacogenomic results (an increasingly common offering at medical centers throughout the country; see “Genetics lands in primary care inboxes,” CAP TODAY, June 2019). For those who opt in, clinically actionable pharmacogenomic variants from the panel will be entered into the medical record and, not incidentally, made available to prescribing caregivers across the UPMC system.

About 5,000 patients—of a targeted 150,000—have been enrolled so far, Dr. Empey reports. The majority of the validation work in the clinical laboratory, the UPMC Genome Center, has been completed, “but we have not yet returned results to the medical record. There’s lots to build in that process, including clinical decision support.”

Though open to any interested UPMC patient, “We believe there’s stronger value in the return of pharmacogenomic results when there’s prescribing or conditions that are likely to have clinical utility,” Dr. Empey says. In other words, they prefer to get their hits with runners already in scoring position. “We’ve started doing analysis within our electronic medical records to understand where prescribing of these medications is highest and where the strongest benefit is. We’ll target recruitment in those areas.”

That’s the dream. Reality often steers ships in other directions, however, and Dr. Empey is well aware that the views of both his colleagues and patients will shape how pharmacogenomics develops.

“When we talk to patients,” Dr. Empey says, “they often assume all drugs can be guided by these new technologies.” Obviously that’s not the case.

If patients are the sunny Maria von Trapp in this scenario, physicians are the dreary Baroness. “When we talk to clinicians in general, they have the opposite opinion,” says Dr. Empey. Their view? Pharmacogenomics is not ready, with little data to support its clinical use.

In reality, as Dr. Empey noted during his AMP talk, nearly 300 medications have some mention of pharmacogenomics in their FDA product labeling. “I don’t want to oversell that,” he says, noting that in some cases that mention might fall quite low in the labeling. “But I use that statistic to get people excited that there actually is quite a bit of data in regulatory guidance. In reality, there’s 30 to 40 medications where there’s strong guidance on how to use testing results if they are available.”

PharmVar (www.pharmvar.org) is a useful resource for laboratories trying to understand varying allele definitions. PharmGKB (www.pharmgkb.org) is another well-established site for annotations and aggregating regulatory information, among other things.

But the real mother lode is the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (https://cpicpgx.org), a resource he mentions repeatedly, like a slogan at a rally. “Everyone should be aware that there are peer-reviewed consensus guidelines on the appropriate use of pharmacogenetic data to guide prescribing and of all the great work that CPIC does,” Dr. Empey says. “The more people are aware of these freely available guidelines, the better we all are as a field about knowing how to use the information appropriately in clinical care.”

Dr. Empey uses the chicken-or-egg reality to describe the current conundrum in the field. One approach is to build evidence-based arguments to justify PGx testing using current costs and projections of value of these data. But in reality, he says, “The guidelines are ahead of that, and imagine a time when these data are ubiquitous—saying that when the data is available, this is how you should use it.”

Institutions will need to decide for themselves when it makes sense to start building the infrastructure to support PGx testing. UPMC, obviously, has reached that tipping point—hence its large population-based study.

He calls himself an optimist—clearly, those hills are alive—and says he likes where the field is heading. Without ignoring the need for more real-world data, he says, “If the data’s available, I’m definitely on the we-should-be-using-it side of things.”

That physician-patient fissure is an interesting place to pause.Patients’ experiences with their medications can resemble encounters with the law—supportive for many, bruising for others. Patients who are frustrated by side effects, costs, etc., may look for other solutions. Pharmacogenomics will not provide answers in every case, Dr. Empey acknowledges, but for someone who’s paying hundreds of dollars or more a month for an antidepressant, say, or antiplatelet medication that might not be working, the allure is appreciable. “You can imagine someone saying, Well, this is a pretty logical solution. Why wouldn’t we do this?”

For Pitt+Me Discovery, the majority of the validation work in the clinical lab, the UPMC Genome Center, has been completed, “but we have not yet returned results to the medical record,” Dr. Empey says, adding, “There’s lots to build in that process, including clinical decision support.” Above, a multidisciplinary team of the UPMC Genome Center and the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy. Clockwise from left: Dr. Empey; Keito Hoshitsuki, PharmD; Lindsey Kelly, PhD; Karryn Crisamore, PharmD; Dara Kozak; and Annerose Berndt, DVM, PhD. (Photo: Scott Goldsmith)

Some clinicians and payers launch from a different angle. Their starting point, Dr. Empey suggests, is, When is it something that I need to do in everybody?

In between lies an opportunity. Dr. Empey’s own institution has joined the slowly growing ranks of sites that offer pharmacogenomics clinics, where patients who are seeking PGx-guided care can talk with a pharmacist and physician familiar with the data—and who will order testing if warranted.

Patient interest is also growing thanks to DNA ancestry testing, a business that has been eyeing health-related testing of late. Health care in general has become much more consumer directed, Dr. Empey observes. “But sometimes our field is critical of direct-to-consumer companies for being outside the clinical environments. In many ways, though, they’re helping to stimulate an important consumer mindset—activating patients to be more and more active in their own health—and that’s a good thing.” For patients, it makes sense to take available genetic information and seek a caregiver and laboratory that will help them understand it, rather than await “a more paternalistic push down from a clinician.”

Dr. Empey sees a chance to seize on that momentum and create an educated audience. His Test2Learn program wrestles with what he calls “the biggest bear” in moving pharmacogenomics forward: How to train the clinicians already in practice?

Interested learners can optionally undergo the genotyping process themselves, and then consider using their own data in their coursework. The program has been deployed in the Pitt School of Pharmacy curriculum for six years and is now offered in nationally deployed certificate and continuing education programs for practicing pharmacists and physicians as well. Dr. Empey’s team has reported strong learning outcomes from this approach.

It’s also possible that patients’ encounters with personalized, PGx-driven medicine will result in more patient satisfaction—a success metric in and of itself. It could also be cost-effective in a more traditional sense. And it could improve patient adherence if it connects patients to a drug that works better, has fewer side effects, or both.

In the midst of all this, Dr. Empey sees an opening for laboratories. “There’s a great role for labs,” he says. In addition to providing high-quality testing and interpretation, “labs can be front and center in emphasizing that these services exist.”

Putting pharmacogenomics testing to work remains an uphill journey—prepare to climb a lot of mountains, if not every one. Dr. Empey and others reported on 12 early adopters of CYP2C19 genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy (Empey PE, et al. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018[4];104:664–674). Their experiences provide useful insight into what can make a PGx endeavor sink or swim, he says.Foremost, “You need a clinician champion to be able to start programs. If you have a great lab or a great research group and you don’t have that [clinical] champion to spearhead implementation, they’re a lot harder to get off the ground.”

Education, as noted, is also critical. Those involved need to know about CPIC and other available resources. As knowledge expands, so will the field. Just as there’s no need to explain to anyone that a poor renal function may require changes in dosing of some medications, he foresees a day when knowing that someone is a CYP2C19 intermediate metabolizer will automatically drive downstream action.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management