Dr. Larsen displayed the CT scan of the patient’s lungs (Fig. 10). “Even I can recognize there’s something wrong in the right lung,” he said. “This is just diaphragm, of course, but there is some sort of patchy, ground glass infiltrate in the right lung and, looking a little more closely, there probably is even some of the same process going on in the left lung, just a lot more subtle.” The problem appears to be bilateral.

Dr. Larsen displayed the CT scan of the patient’s lungs (Fig. 10). “Even I can recognize there’s something wrong in the right lung,” he said. “This is just diaphragm, of course, but there is some sort of patchy, ground glass infiltrate in the right lung and, looking a little more closely, there probably is even some of the same process going on in the left lung, just a lot more subtle.” The problem appears to be bilateral.

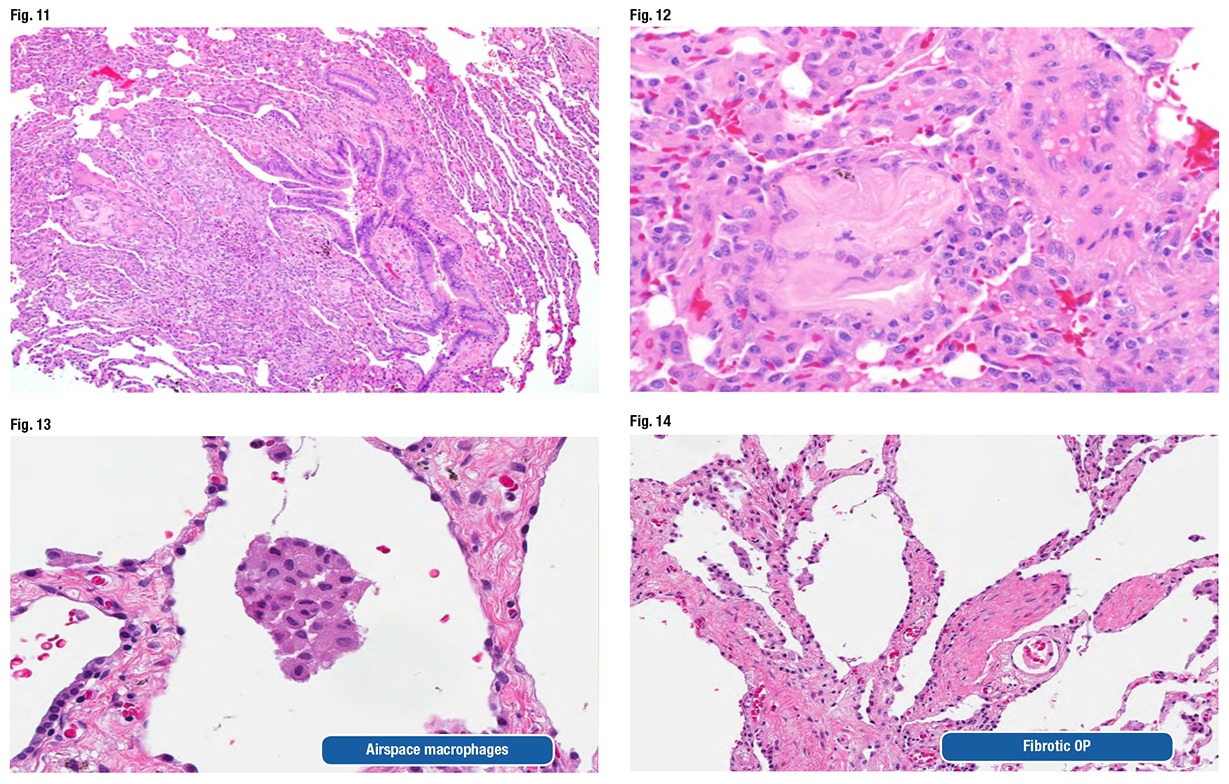

He also looked at the biopsy and confirmed everything the original pathologist found. Then he recognized the culprit. One of the fragments of aspirated food looks “almost like a light pink letter S that has a little dark purple eye in the middle of it,” at about nine o’clock in the periphery of the biopsy at low power, Dr. Larsen told CAP TODAY (Fig. 11). Another fragment shown at high power is the “irregular pink blob that’s just to the left of center.” (Fig. 12).

He also looked at the biopsy and confirmed everything the original pathologist found. Then he recognized the culprit. One of the fragments of aspirated food looks “almost like a light pink letter S that has a little dark purple eye in the middle of it,” at about nine o’clock in the periphery of the biopsy at low power, Dr. Larsen told CAP TODAY (Fig. 11). Another fragment shown at high power is the “irregular pink blob that’s just to the left of center.” (Fig. 12).

“This amorphous eosinophilic stuff is not really recognizable as food anymore, but this, in our experience at least, tends to be one of the most common types of fragments encountered with people who aspirated,” Dr. Larsen said. The fragments “can be really tricky, and if you are going quickly, you will gloss over this, thinking it’s just some sort of fibrous tissue that is sort of a little weird in the interstitium, but in fact that is aspirated foreign material.”

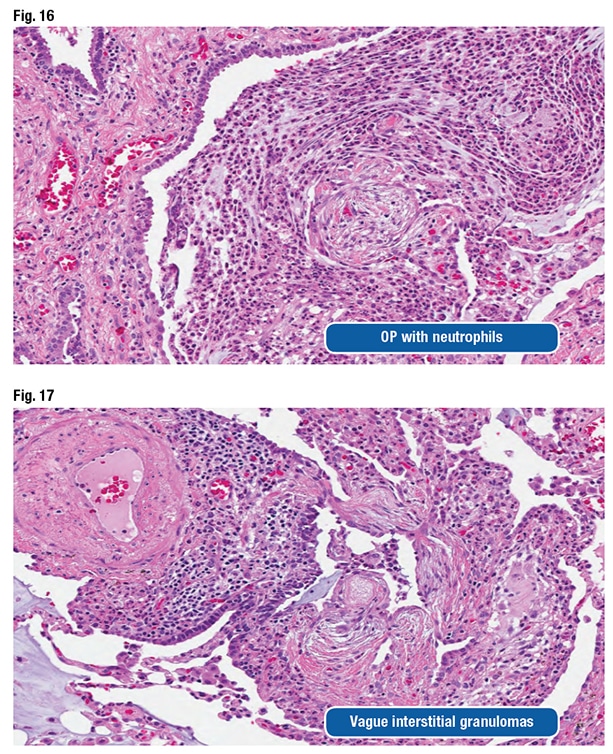

The patient’s consult diagnosis was diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis and pneumonitis. Dr. Larsen presented Table 1 from an article by a Mayo Clinic pulmonologist and colleagues (Hu X, et al. Chest. 2015;147[3]:815–823). The syndromes include problems of the airways, Dr. Larsen said, pointing out diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis, which chronically can lead to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

The patient’s consult diagnosis was diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis and pneumonitis. Dr. Larsen presented Table 1 from an article by a Mayo Clinic pulmonologist and colleagues (Hu X, et al. Chest. 2015;147[3]:815–823). The syndromes include problems of the airways, Dr. Larsen said, pointing out diffuse aspiration bronchiolitis, which chronically can lead to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

All of the risk factors listed in Table 2 (Hu X, et al. Chest. 2015;147[3]:815–823) should be apparent, Dr. Larsen said: dysphagia, altered mental status owing to excessive alcohol, neurologic disorders, esophageal disorders, vomiting, GERD, etc. “Lots of things can lead to aspiration,” he said. “So always include aspiration in your differential for airway-centered inflammatory or fibrotic processes.”

The Chest article says “the presence of foreign material on the lung biopsy can be easily overlooked by pathologists, resulting in misdiagnosis.”

“This is a clinician’s statement,” Dr. Larsen said. “A little presumptive, right? We are pathologists. How can you tell us that we have missed food in our biopsies?” But he said the statement is completely accurate. Some of the food fragments actually polarize. “So tossing your polarizing filter on your scope and taking a second look sometimes can be helpful not to miss stuff, although not everything that is aspirated polarizes.”

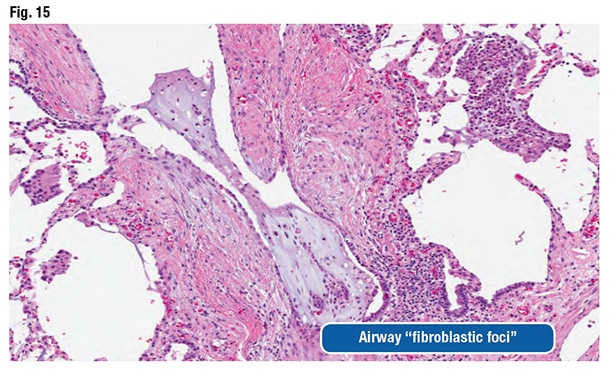

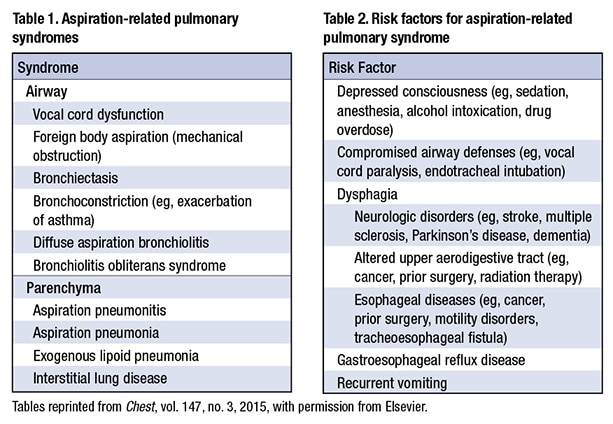

The pathologic features can be nonspecific and variable, as they were in this case, Dr. Larsen said. Airspace macrophages can appear foamy and even resemble drug-reaction macrophages (Fig. 13). “You can see organizing pneumonia” and sometimes fibrosing organizing pneumonia (Fig. 14). Fibroblast foci might be observed around the airways. “They look like fibroblast foci in a fibrotic ILD like a UIP [usual interstitial pneumonia] pattern-type fibroblast focus, but they are in the wrong spot,” he said. “They are around the airways.” (Fig. 15).

The pathologist could also see acute and chronic bronchiolitis, vasculopathy, vague interstitial granulomas, and organizing pneumonia with neutrophils. “You sort of wonder if that has secondary infection related to aspiration,” he said (Figs. 16 and 17).

The pathologist could also see acute and chronic bronchiolitis, vasculopathy, vague interstitial granulomas, and organizing pneumonia with neutrophils. “You sort of wonder if that has secondary infection related to aspiration,” he said (Figs. 16 and 17).

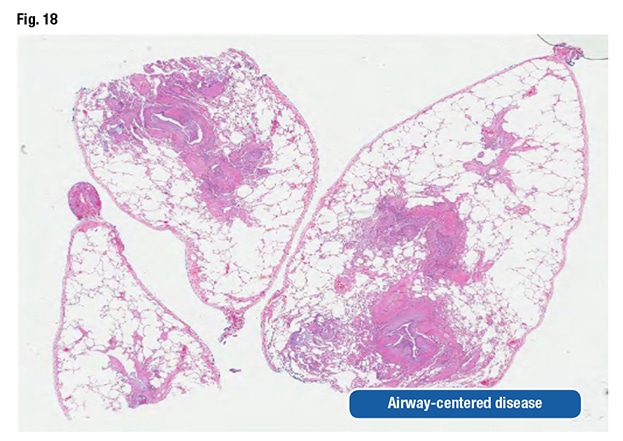

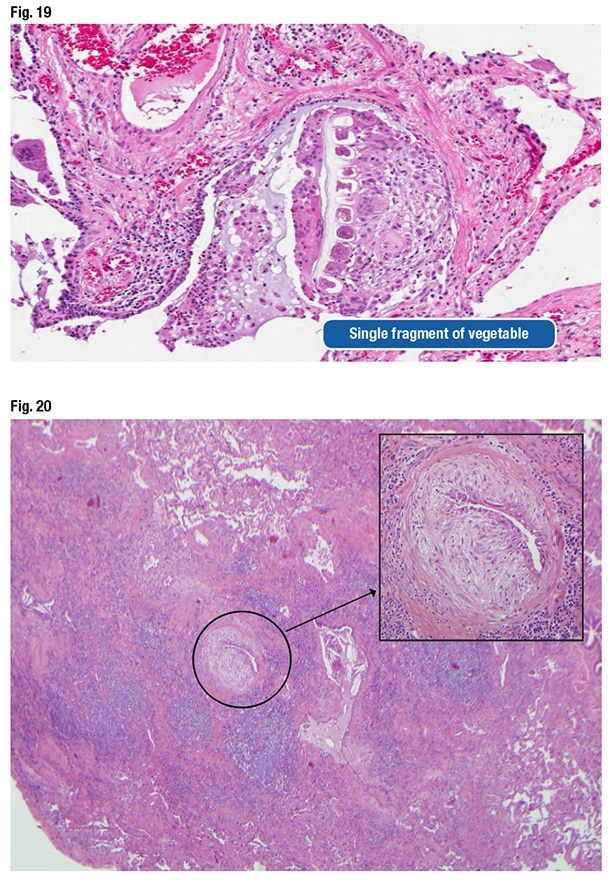

Dr. Larsen presented an image of prominent airway disease at low power (Fig. 18). “When I see abnormalities like that, aspiration gets really high on my differential. In this particular case, only a single fragment of aspirated vegetable material was seen, even though there were all those other changes,” he said, referring to a second image (Fig. 19). “You have got to search for this, but in an appropriate context, this is absolutely diagnostic of aspiration as the cause.”

With airway-centered disease, the pathologist has to consider aspiration. “Even if you can’t find food and prove it, you still need to suggest it to the clinicians because they can actually do something about it.”

With airway-centered disease, the pathologist has to consider aspiration. “Even if you can’t find food and prove it, you still need to suggest it to the clinicians because they can actually do something about it.”

Dr. Larsen also shared a case they became aware of when a Mayo Clinic clinician asked them to look at a wedge biopsy of a patient diagnosed with UIP a decade earlier. The clinician said it didn’t make sense that the patient has UIP and is still alive. “So we re-reviewed the case,” Dr. Larsen said, pointing out structures in the biopsy that look like fibroblast foci (Fig. 20). “You can see why somebody might have started to think about UIP, because there’s scar here, but also all of this centrilobular inflammatory injury.” However, “this fibroblastic proliferation is not at the front of progressive scar. It’s actually occurring within an airway. It’s submucosal fibroblastic proliferation that, in this case, demonstrated aspirated food particles that had been missed initially.” The patient had chronic aspiration pneumonia with scar formation imitating UIP. (No food fragments are in the photo, Dr. Larsen says, but they can be found elsewhere in the biopsy.)

Dr. Larsen also shared a case they became aware of when a Mayo Clinic clinician asked them to look at a wedge biopsy of a patient diagnosed with UIP a decade earlier. The clinician said it didn’t make sense that the patient has UIP and is still alive. “So we re-reviewed the case,” Dr. Larsen said, pointing out structures in the biopsy that look like fibroblast foci (Fig. 20). “You can see why somebody might have started to think about UIP, because there’s scar here, but also all of this centrilobular inflammatory injury.” However, “this fibroblastic proliferation is not at the front of progressive scar. It’s actually occurring within an airway. It’s submucosal fibroblastic proliferation that, in this case, demonstrated aspirated food particles that had been missed initially.” The patient had chronic aspiration pneumonia with scar formation imitating UIP. (No food fragments are in the photo, Dr. Larsen says, but they can be found elsewhere in the biopsy.)

Aspiration is not invariably unilateral, he cautions. “We are taught in medical school that people aspirate into the right lower lobe,” which is the quickest and easiest location for food to go when a person aspirates it into the lungs. “But remember, it sort of depends on how you sleep at night.” A person who sleeps on the left side isn’t going to aspirate into the right lower lobe; it will go into a different lobe. “And if you happen to roll in the middle of the night into a different position and then aspirate again, you are going to get aspiration involving some other spot.” Therefore, aspiration is often multifocal and can be bilateral.

Dr. Larsen reminded the audience that the patient in the case had “preferential involvement of the right side, which is interesting, and should make you think about aspiration, but there are bilateral abnormalities that should not dissuade you from suggesting that possibility.”

The pearl for the case: “Aspiration-induced injury may be more common than you think.” Dr. Larsen reported signing out a case one day earlier in which the pathologist identified the inflammatory process, the bronchiolitis, and the organizing pneumonia. “But they completely missed the fragments of aspirated food within that process that would have clinched that diagnosis had they recognized them. We see pathologists missing this almost on a daily basis in our consultation practice. It’s one of the more common problems that trip people up.”

Karen Lusky is a writer in Brentwood, Tenn. Part one was published in the June issue of CAP TODAY. Drs. Larsen and Smith will present all 10 of their cases at CAP19 in Orlando, Fla., Sept. 21–25.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management