Charna Albert

March 2023—With endometrial carcinomas and other gynecologic tumors, molecular testing matters, and not only at the diagnostic stage. “We’re rapidly evolving,” said Leslie M. Randall, MD, MAS, division director of gynecologic oncology, Virginia Commonwealth University Health, speaking at CAP22. “These molecular results are already starting to affect our treatment choices.”

In a session titled “Beyond the Correct Diagnosis: Ancillary Testing in Gyn Pathology—Things Your Gyn Onc Doesn’t Want You to Miss,” Dr. Randall, who is also Dianne Harris Wright professor at VCU, and Sadia Sayeed, MD, assistant professor of pathology and director of cytopathology, VCU Health, discussed the molecular classification of endometrial, ovarian, and cervical cancer and used their cases to illustrate emerging practices in testing and treatment. One topic discussed: Mismatch repair deficiency, once used primarily to test for Lynch syndrome, has other potential downstream effects in a patient with endometrial cancer, Dr. Sayeed said. “And that’s the part that the pathologist might not be as well informed about.”

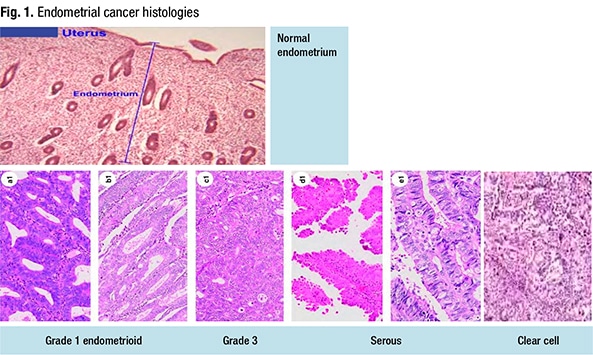

There are five histologic types of endometrial carcinoma, Dr. Randall said (Fig. 1). The three endometrioid tumors range from grade one to grade three, with grade two “an architectural distinction that probably doesn’t have any molecular biological bearing.” The serous tumors are more aggressive and “more p53-mutated.” And the clear cell endometrial carcinomas have the same characteristics as ovarian clear cell tumors but originate in the endometrium. Patients with clear cell endometrial carcinomas have a good prognosis in the early stages and a poorer prognosis at the advanced stages, “probably because we haven’t picked up the right treatments for those patients yet.”

The Cancer Genome Atlas isolated four molecular subtypes of endometrial cancer, Dr. Randall said: POLE ultramutated; MSI hypermutated; copy-number low, or endometrioids (“which are probably our hormonally driven cancers—those grade one tumors”); and copy-number high, or serous-like tumors (Levine D, et al. Nature. 2013;497:67–73). “But there are a group of endometrioid tumors that are in the serous-like group, and they’re mostly the p53-mutated tumors,” she said.

“There’s a practical reason that we’re looking at these tumor types,” Dr. Sayeed said—overall survival and progression-free survival differ by molecular subtype, with POLE ultramutated having the best survival and serous-like morphology the worst, and mismatch-repair deficient in between. Talhouk, et al., in 2015 reported their use of the TCGA data set to develop surrogate assays that could replicate the TCGA classification. They used mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry instead of microsatellite instability testing and used p53 IHC as a surrogate for copy-number status (Talhouk A, et al. Br J Cancer. 2015;113[2]:299–310). They could not find a surrogate for POLE mutation status. “You have to do next-generation sequencing to find that mutation,” Dr. Sayeed said. The World Health Organization in 2020 discussed a new classification based on the TCGA, grouping the four molecular subtypes into mismatch-repair deficient, p53 mutant, POLE ultramutated, and a fourth group with no specific mutation.

Testing for molecular subtype, Dr. Randall said, “can be particularly helpful if you have a grade two and you want to know how aggressive this tumor is, because it’s on the line. Stage is going to matter, but so will knowing which molecular subtype it falls into.” At VCU, the testing is performed in-house, and she and colleagues know the MSI, POLE, and p53 findings for their patients.

The subtype now has bearing on treatment outcomes, she said. This was illustrated by the European prospective clinical trial PORTEC-3, which investigated the benefit of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for patients with high-risk endometrial cancer (de Boer SM, et al. Lancet Oncol. 018;19[3]:295–309). “The point of the study was to see if chemotherapy provided an overall survival advantage,” she said. “What they found was for the intent-to-treat population, there was no difference in survival with the addition of chemotherapy.” But in the U.S., “we had this evolving paradigm where chemo was better than radiation,” she said. “So things were inconsistent, and it turns out it was the molecular subtype that was making the results inconsistent.”

A follow-up study investigated prognosis and impact of chemotherapy for each molecular subgroup using tissue samples from PORTEC-3 trial participants (León-Castillo A, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38[29]:3388–3397). In that study, patients with p53-abnormal endometrial cancer had a highly significant benefit from combined adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy (CTRT) compared with radiotherapy (RT) alone. The p53-abnormal group had an absolute difference of 22.4 percent for relapse-free survival (five-year RFS: 58.6 percent with CTRT versus 36.2 percent with RT; HR, 0.52; 95 percent CI, 0.30–0.91), and an absolute difference of 23.1 percent for overall survival (five-year OS: 64.9 percent [CTRT] versus 41.8 percent [RT]; HR, 0.55; 95 percent CI, 0.30–1.00).

Only one patient with a POLE-mutated endometrial cancer (treated with RT alone) had disease recurrence, resulting in a five-year relapse-free and overall survival of 100 percent with CTRT versus 96.6 with RT. Patients with mismatch-repair deficient endometrial cancer had a five-year relapse-free survival of 68 percent with CTRT versus 75.5 percent with RT, and a five-year overall survival of 78.6 percent with CTRT versus 84 percent with RT. The lack of benefit observed from the addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy in patients with mismatch-repair deficient endometrial cancer suggests a favorable outcome with RT alone in stage one and two disease, the authors write.

“Now we’re learning,” Dr. Randall said, “not only do they [patients with mismatch-repair deficient endometrial cancer] not benefit from chemotherapy, these patients probably are better treated with immunotherapy.” In clinical trials, she said, MMR-proficient patients now are receiving chemotherapy without immunotherapy, “and if they’re deficient, we’re looking at immunotherapy versus chemotherapy. So those patients may get immunotherapy in the first line of treatment,” she said, which could be curative. Whether the mutation is germline or somatic doesn’t seem to be consequential, nor does it matter if there is hypermethylation, “or, say, true loss of MLH1 or PMS2. But mismatch repair status is extremely important. So at the bare minimum, mismatch repair status needs to be reported,” she said. Whether on the biopsy or on the final hysterectomy specimen, “at some point that tumor has to be tested for mismatch repair deficiency.”

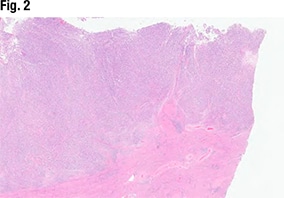

Dr. Sayeed shared the case of a 67-year-old woman who presented with postmenopausal bleeding. The hysterectomy specimen (Fig. 2) revealed a large endometrial tumor, invasive into the myometrium as well (far right). “From this view it looks solid—so not able to see any glandular lumens or glandular morphology, but it does look like a high-grade and solid tumor filling up the endometrium.”

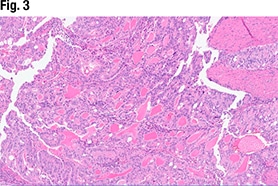

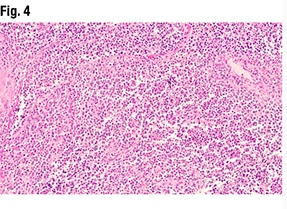

Another part of the tumor (Fig. 3) did show glandular formations, she said, noting that scattered throughout the image are glandular lumens filled with eosinophilic secretions. “The glands themselves are close to pseudostratified in appearance—variable size in the nuclei but not wildly pleomorphic,” she said, and without significant mitotic activity. “Very back-to-back, not seeing very much intervening stroma. So based on this morphology it looks like an endometrioid tumor that is pretty much all gland forming.” But in other areas (Fig. 4), “we see much more solid morphology—it’s not forming glands, it’s not forming papillary structures, it’s very monotonous in appearance,” and it has a high nucleus-to-cytoplasmic ratio. “We do get a sense that there’s mitotic activity,” she said. “So very high grade, very solid. This is not forming any glands at all.”

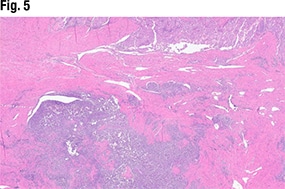

In Fig. 5 is another view of the myometrial invasion, with the myometrium shown in pink. In the purple portion of the image, “you can see these large nests of this more poorly differentiated part of the tumor infiltrating into the myometrium. So deeply invasive, solid, and some with glandular morphology,” she said.

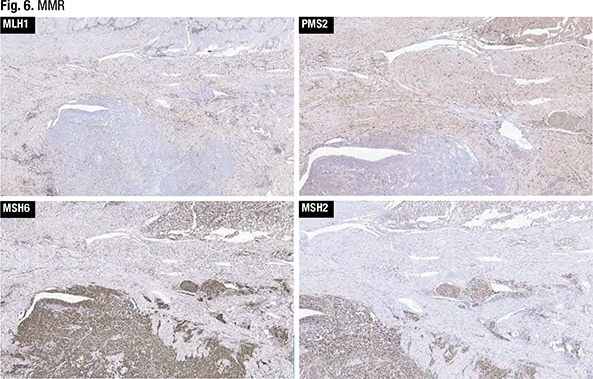

IHC for MMR was performed (Fig. 6). “With any mismatch repair testing interpretation,” Dr. Sayeed said, indicating the MLH1 testing, “you want to make sure you have some internal positive control cells. And here you can see a sprinkling of cells within the myometrium—potentially lymphocytes—that are positive.” Both the glandular-forming areas of the tumor and the more solid areas seen in the myometrial invasion had loss of mismatch repair for MLH1, she said.

IHC for MMR was performed (Fig. 6). “With any mismatch repair testing interpretation,” Dr. Sayeed said, indicating the MLH1 testing, “you want to make sure you have some internal positive control cells. And here you can see a sprinkling of cells within the myometrium—potentially lymphocytes—that are positive.” Both the glandular-forming areas of the tumor and the more solid areas seen in the myometrial invasion had loss of mismatch repair for MLH1, she said.

There was some PMS2 staining in the glandular areas of the tumor, she said, “and maybe focally lost in the solid.” MSH6 and MSH2 showed intact expression. “So based on the loss of mismatch repair in this example, we called this a FIGO grade three endometrioid adenocarcinoma,” she said. “Much more of it was solid than the well-differentiated component, and because of the loss of mismatch repair, we called it mismatch-repair deficient FIGO grade three endometrioid carcinoma.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management