Karen Lusky

August 2020—Tumor budding is a robust prognostic marker that should be reported at least in pT1 and stage II colorectal carcinomas and taken into account with other risk factors. Further evidence is needed for tumor budding assessment in specimens taken after neoadjuvant therapy, says Heather Dawson, MD, senior staff GI pathologist at the Institute of Pathology, University of Bern in Switzerland.

Dr. Dawson, whose group has studied budding in CRC for more than 15 years, made those points and others in a recent CAP TODAY interview and in a CAP19 session on prognostic factors in CRC.

Tumor budding is defined as single tumor cells or clusters of up to four tumor cells at the invasive margin of CRC. “We know from many studies they play a role in the tumor microenvironment,” Dr. Dawson says. They’re involved in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and viewed as the “morphological correlate of this process.”

Ueno H, Kajiwara Y, Shimazaki H, et al. New criteria for histologic grading of colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(2):193–201. https://journals.lww.com/ajsp/pages/default.aspx. The Creative Commons license does not apply to this content. Use of the material in any format is prohibited without written permission from the publisher, Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Please contact permissions@lww.com for further information.

Tumor buds are an independent prognostic factor in most studies, she says, but their predictive value isn’t yet known. Anything with five or more tumor cells qualifies as a poorly differentiated cluster, or PDC. “PDCs are basically tumor buds’ big brother, and they have been shown to have a prognostic value on their own. There is no consensus upper limit of the PDC. Many studies just use an arbitrary cutoff of up to 20 cells.” (Fig. 1).

If there are a lot of tumor buds, the tumor appears to act in a more malignant fashion, says Raul S. Gonzalez, MD, associate professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School, who spoke on tumor deposits in the CAP19 session (CAP TODAY, July 2020). “The tumor metastasizes more readily and has a worse prognosis,” he says.

When pathologists calculate a pT and pN classification for colorectal cancer, “the TNM classification system works very well but has one weakness,” Dr. Dawson cautions, “in that it only fits into the anatomical distribution within the body.” This is especially apparent in stage II colorectal cancers. “You have a wide span of prognosis within the same stage. And a lot of stage II patients actually do worse than their stage III counterparts. So this is why we need additional biomarkers for better risk stratification within a certain tumor stage,” she says.

Few potential biomarkers fill all of the requirements needed to be implemented into practice, Dr. Dawson says, and the REMARK guidelines were put in place to promote a higher level of quality in biomarker reporting in studies. So what can be expected from an optimal biomarker? she asks. “This would be a marker that is driven by hypothesis and backed by a considerable level of evidence in the literature. It needs to be reproducible, and it certainly has to have some sort of meaning, a prognostic effect, and ideally also predictive power. It has to be cost-effective and easy to implement. So we are looking for tumor budding as a biomarker to check all of these boxes” (Altman DG, et al. PLoS Med. 2012;9[5]:e1001216).

For tumor budding to be used in routine reporting, consensus was needed, Dr. Dawson says, and important questions needed to be addressed. Where should tumor budding be assessed within a tumor? “What will be the optimal field number and size of the field where we should be counting tumor budding? Should we even be counting tumor budding or just eyeballing it? And should this be done on H&E or immunohistochemistry?”

Different groups advocated for different methods over the years. “So there were a lot of potential scoring systems out there, and we knew that if tumor budding was ever going to make it into the clinic, we would need to have some sort of consensus scoring method,” Dr. Dawson says. That was the goal of the 2016 International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) in Bern, Switzerland (Lugli A, et al. Mod Pathol. 2017;30[9]:1299–1311). “We wanted to establish a set of guidelines that was based on the highest level of evidence in the literature.”

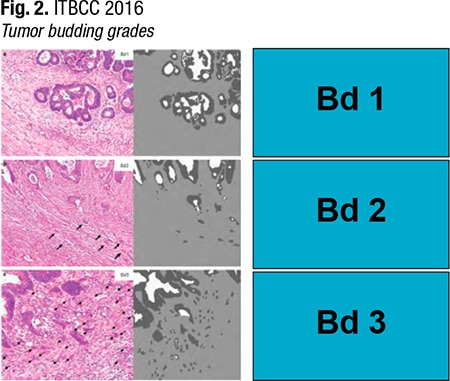

The first step in the ITBCC consensus method for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer is to define the field (specimen) area for the 20× objective lens of the microscope based on the eyepiece field number diameter. When looking at the slides and inspecting the invasive front for lymphovascular invasion, tumor grade, depth of invasion, perineural invasion, and so on, make a “mental note” of where the most buds are, Dr. Dawson says, adding, “This can really be done by eyeballing.” Then return to that slide and scan all of the invasive material. “Do that until you feel comfortable that you have identified the hotspot. At that hotspot, go up to 20× and then count the tumor buds you see. Then you will end up with a number.”The pathologist has to determine whether to normalize this number. “So what is this normalization? The ITBCC method is standardized for an area of 0.785 millimeters square,” she says. And that is the area that pathologists are seeing at 20×, if their field number diameter is 20 mm. “In Japan, a lot of pathologists use 20-millimeter field number diameter eyepieces. And unfortunately in North America and Europe, many of us use 22-millimeter field number diameter eyepieces.” The area at 20× is 0.950 mm2. “So you need to divide the number of buds by 1.21.” Next check whether the number of buds corresponds to Bd1, Bd2, or Bd3. (Bd1 is zero to four buds, Bd2, five to nine buds, and Bd3, 10 buds or more.) “This is low-, intermediate-, or high-grade tumor budding.”

Reprinted by permission from Copyright Clearance Center: Springer Nature, Modern Pathology. Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, et al. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(9):1299–1311. Copyright 2017.

Members of the ITBCC intentionally chose a three-tier system because it accommodates clinical situations that have different clinical endpoints. “So you can use a three-tier system for endoscopically resected pT1 colorectal cancers where having Bd1 is okay, but as soon as you get into Bd2 or Bd3, this is considered a risk factor for lymph node metastases.” A three-tier system can also be used for stage II patients, where the endpoint is tumor recurrence and patient survival, Dr. Dawson says. “So you have to set your threshold a bit higher. And in these cases, Bd1 and Bd2 are tolerated, and only Bd3 is considered a risk factor.” (Fig. 2).

At the consensus conference, there was also dialogue about whether pathologists should report the number of buds they see, or just the cutoffs, which would be Bd1, Bd2, and Bd3. “Cutoffs are very convenient for clinicians because it makes clinical management so much easier if something falls into a category,” she says, “but the truth is that budding lies on a biological spectrum. So cutoffs will ultimately mischaracterize the extent of risk variation within a certain group.” For example, say two patients have colorectal cancer, one with 11 tumor buds and the other with 200. “They are both high-grade budders, but which of the tumors is more aggressive?” It is the patient with 200 buds because the risk rises per bud. So pathologists should report the number of buds and the grade category, she says.

The ITBCC criteria were implemented in the 2017 version of the CAP protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. “That was a very important step toward getting tumor budding entered and into routine reporting,” Dr. Dawson says. “We report tumor budding because it has potential impact on prognosis and benefit to patients. And besides the CAP protocol, it was also important for us to get tumor budding into other major guidelines. And we were happy to see tumor budding listed as an additional prognostic factor by the Union for International Cancer Control.”

pT1 colorectal cancers are the clinical scenarios that have been best studied for tumor budding. “Here we are interested in budding as a predictor of lymph node metastases,” she says, and the clinical decision that has to be made is whether the patient needs a resection. “How high is the risk of the patient having lymph node metastases? Or can we have a good conscience and sleep well at night just leaving the patient alone?”A systematic review published in 2013 found the strongest independent predictors of lymph node metastasis to be lymphatic invasion, submucosal invasion ≥ 1 mm, tumor budding, and poor histological differentiation (Bosch SL, et al. Endoscopy. 2013;45[10]:827–834).

A meta-analysis published in 2017 found a strong association between the presence of tumor budding and risk of nodal metastasis in pT1 CRC (Cappellesso R, et al. Hum Pathol. 2017;65:62–70).

Another clinical scenario is stage II CRC where the pathologist isn’t forecasting lymph node metastasis, she says, but instead looking at tumor budding as a factor for tumor progression and patient survival. “The clinical decision that needs to be made here is can or should a patient receive adjuvant chemotherapy?”

In stage II CRC, Dr. Dawson says, “it is a real matter of debate if patients should get chemotherapy or not.” Stage II has a “huge spectrum” of patients, she says, some of whom live a long time with their disease and others who have aggressive tumors. Pathologists “are under pressure to select patients who have aggressive disease. That is where tumor budding comes in because high-grade tumor budding predicts aggressive disease.”

Numerous studies have found that “tumor budding is prognostically relevant independent of stage. That’s why you can argue that tumor budding is important information across all stages of colorectal cancer. But for treatment management decisions, tumor budding will not play a role in stage III and stage IV.” The level of evidence in the literature is sufficient to support reporting of tumor budding in pT1 and stage II colorectal cancer.

Preoperative biopsies of colon and rectal cancer are the third clinical scenario and one she describes as promising. “If we could take information from a preoperative biopsy and predict clinical response to neoadjuvant therapy, this would be very useful for patients,” she says. Intratumoral budding is associated with higher T stage, higher N stage, and other aggressive features such as lymphovascular invasion. It is also associated with peritumoral budding and with survival. Here too the increased number of tumor buds presents a greater risk. “Again this is all on a biological spectrum,” she says.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management