Sherrie Rice

March 2021—If you see vascular changes, report them.

That is the advice Kristen L. Veraldi, MD, PhD, pulmonary critical care physician, University of Pittsburgh Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Disease, gave last fall in a CAP20 virtual session on vascular changes in lung biopsies—when and what to report.

She and co-presenter Frank Schneider, MD, associate professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University, talked back and forth about vasculitis—what it means, what it does clinically, whether it matters.

“Is it true,” Dr. Schneider asks Dr. Veraldi, “that most patient biopsies have vascular changes that don’t matter to the patient? How often would I see a biopsy that is done for an abnormal vessel?”

Depending on the patient and clinical context, the pulmonologist will have a pretest probability for different observed findings. “If someone has a picture of significant pulmonary hypertension,” Dr. Veraldi says, “hopefully we’ve determined that already based upon exam, on diagnostic testing—for example, cardiac echo, right heart catheterization. We really aren’t sending those patients for lung biopsy. In other patients, we may be expecting to confirm a clinical suspicion of a vasculitis, in which case we should be communicating that with our pathologist in advance of the biopsy.”

The gray area, she says, is when unexpected findings are seen that the pulmonologist must explain with additional history or diagnostic testing. “We need to understand if the vascular changes are out of proportion to other findings in the biopsy, details about what the vessels look like to you, how pervasive the abnormality is.” The analogy would be understanding whether there is one tiny incidental granuloma versus sufficiently profound granulomatous change to support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis, Dr. Veraldi says.

“So we don’t necessarily need a firm diagnosis as much as a robust description of what you’re seeing so we can include that piece of the puzzle in the larger picture and develop a management plan for the patient. For example, we’ll want to make an assessment about whether these changes may herald the evolution of future clinically significant vascular disease that will impact not only our immediate diagnostics, but also inform our plan for routine monitoring and future testing.”

If pathologists see vascular changes, she says, clinicians want to know about it. “And then it’s up to us to figure out what it means.”

“I’d rather know it now than go back and identify it in retrospect in a few years when we re-review,” Dr. Veraldi says. The comment “uncertain significance—correlate clinically” is always acceptable, she adds.

Vasculitis is an inflammation of the blood vessels that, for some, means inflammation will be seen in the media, Dr. Schneider says. In reality, the intima is sometimes inflamed in blood vessels, he says. “The adventitia is also a component of the blood vessel. If you have only cuffing of the blood vessel in the adventitia by inflammatory cells, it’s probably the most tricky to decide whether there is vasculitis or not, but let’s just go with inflammation of the blood vessels,” and based on Dr. Veraldi’s advice, there should be a low threshold of noticing it and reporting it.The small vessel vasculitides are associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), with immune complexes, or with an autoimmune disease. The secondary vasculitides are caused by autoimmune diseases or malignancy or are drug induced. “And I must say that of all vasculitides I see in the lung, all comers, I see it in infections. They are very common around infections,” Dr. Schneider says.

What should pathologists look for in the medical record that would help them determine whether the vasculitis they see is significant versus an innocent bystander in another disease process? Dr. Schneider asks Dr. Veraldi.

“This is playing the ‘guess what I’m thinking’ game with your clinician,” she says. Start by looking for what serologies they’ve ordered, she advises, even if they’re not resulted yet, because that’s a clue about what the clinician is thinking. Also helpful are the data from the cardiac echo or right heart catheterization. “And if we’ve done a good job of documenting our thought process, then we may have discussed in our clinical differential what we’re thinking about, what’s highest on the list, what’s lower on the list, why we’ve decided to pursue biopsy,” Dr. Veraldi says.

If that’s not clearly expressed in the clinical notes, talk to the clinician. Time doesn’t always permit, but even a quick email sometimes can help fill in some of the blanks, she says. “Hopefully, we’ve done a pretty good job of leaving that bread crumb trail in our documentation and with the studies that we’ve ordered leading up to that biopsy for you to figure out what we’re thinking about.”

The 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides (Fig. 1) divides vasculitides into three categories, and its purpose, Dr. Schneider says, is to lead everyone, when a set of changes is seen in the vessels, to call it the same thing. “None of these changes are necessarily specific for any particular disease. Many are defined by the presence or absence of necrotizing vasculitis and the presence or absence of immune complexes or of ANCAs. But the point is that the main disease process with the large vessel vasculitis will be in a large vessel.”

That doesn’t mean it can’t involve an intraparenchymal vessel, Dr. Schneider says. “Sometimes you wonder if you see transient arteritis in a larger pulmonary artery. Hopefully you won’t see those in a peripheral wedge biopsy, but it’s a possibility. As with polyarteritis nodosa, it is more of a medium vessel vasculitis.” But what is usually seen in the lung, he says, is a full spectrum of ANCA-associated vasculitides, which, in this classification, are divided into three types.

“If you see a vasculitis that involves one of these vessels or one certain caliber vessel, should I as a pathologist be able to put that name on it and diagnose it? And I think the answer to that is no.”

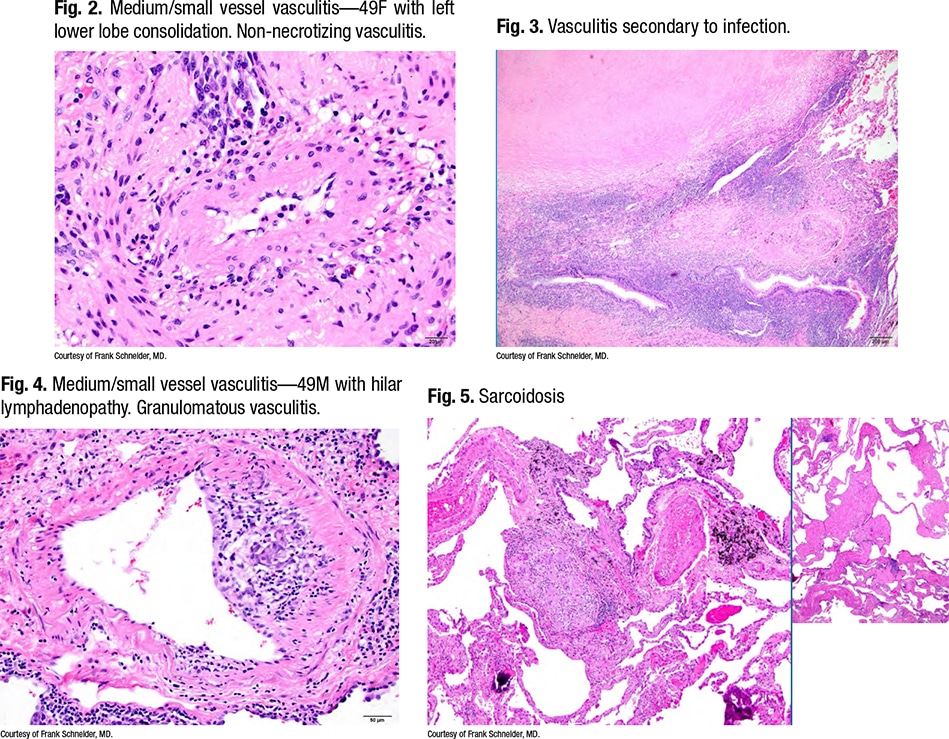

Dr. Schneider points to an image of a medium/small vessel vasculitis (Fig. 2) taken from a 49-year-old woman who had a left lower lobe consolidation. Seen on the slide was a non-necrotizing vasculitis. “What you notice is that this vasculitis is set in a bronchovascular bundle that is immediately adjacent to a very large necrotizing granuloma which, to me, looks like an infectious granuloma. It has a very pale pink, fine granular necrosis, and indeed this ended up having Histoplasma organisms in it.” (Fig. 3).

There is vasculitis next to a granuloma, he says, noting it’s common for infectious disease lung biopsies to have secondary vasculitis, “as an innocent bystander.”

“As a pathologist, I always wonder: Could this patient have two diseases—both fleas and lice, as it’s often said?”

“As a pathologist, I always wonder: Could this patient have two diseases—both fleas and lice, as it’s often said?”

He asks Dr. Veraldi: How often do you see patients who have a necrotizing granuloma and then coincidentally have a coexisting systemic vasculitis syndrome that would have been missed had it not been reported?

“It’s not common,” Dr. Veraldi says, and the hope is that this possibility would have been considered in advance. “On rare occasions we’re surprised by microbiology results from surgical tissue if our history didn’t suggest risk factors for more uncommon infections.” She recalls a case in which she and colleagues had difficulty deciding whether a patient had granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, Wegener’s) or if the lung abnormalities were entirely driven by infection. “Our patients are always allowed to have both. Ultimately, in this case, we ended up making the diagnosis of, yes, fleas and lice. This is someone who was treated for her Histoplasma and then ended up with persistent abnormalities that supported a true diagnosis of GPA.”

Before considering immunosuppression, she and colleagues will always err on the side of treating infection and collaboration with infectious disease colleagues if there’s any doubt. “So, overall, relatively uncommon as a new diagnosis from a surgical biopsy, and if we’re hunting for infection on transbronchial biopsies, hopefully we’ve communicated this with you in advance,” she says of the pathologist. Dr. Schneider says he therefore would report this as a necrotizing granuloma “and say there is focally a little bit of vasculitis that I presume is secondary to the infection.”

Before considering immunosuppression, she and colleagues will always err on the side of treating infection and collaboration with infectious disease colleagues if there’s any doubt. “So, overall, relatively uncommon as a new diagnosis from a surgical biopsy, and if we’re hunting for infection on transbronchial biopsies, hopefully we’ve communicated this with you in advance,” she says of the pathologist. Dr. Schneider says he therefore would report this as a necrotizing granuloma “and say there is focally a little bit of vasculitis that I presume is secondary to the infection.”

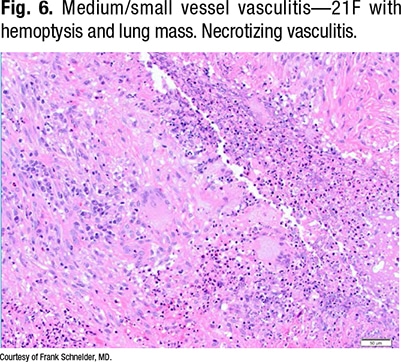

Fig. 4 is a granulomatous vasculitis in a patient with sarcoidosis (Fig. 5). “The important feature is that this kind of fibrosis and the granulomatous infection follows lymphangitic routes,” Dr. Schneider says, “so it’s a characteristic distribution. And it turns out that on wedge biopsies, probably 60, 70 percent of all sarcoid biopsies have vasculitis in them.” He generally doesn’t comment on them.

“Should I be commenting on this?” he asks Dr. Veraldi. Does she treat sarcoidosis patients with vasculitis differently than sarcoidosis patients without vasculitis?

“We don’t,” she says. “We make decisions about routine monitoring and the need for systemic immunosuppression—whether to start it and what medications to use—based on the overall clinical picture and not just the biopsy findings.”

“We don’t,” she says. “We make decisions about routine monitoring and the need for systemic immunosuppression—whether to start it and what medications to use—based on the overall clinical picture and not just the biopsy findings.”

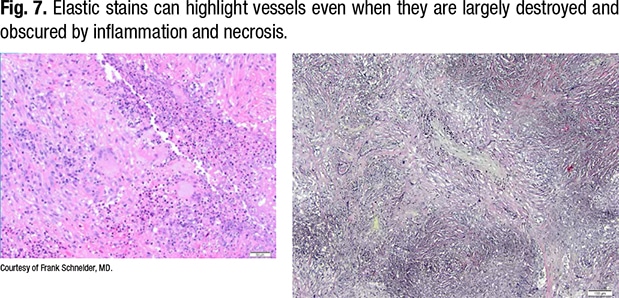

Fig. 6 is a 21-year-old with hemoptysis and a lung mass. “There’s a necrotizing vasculitis, and if someone showed that to me, I would ask them to prove to me that it’s a vasculitis,” Dr. Schneider says. “All I see is necrosis and some giant cells, so it’s something granulomatous with vasculitis, and that’s where your elastic stains come in.”

In Fig. 7, on the right of the same field (lower power), the outline of the vessel can be seen. The lumen is obliterated by organization, and the internal elastic of the vessel can be seen.

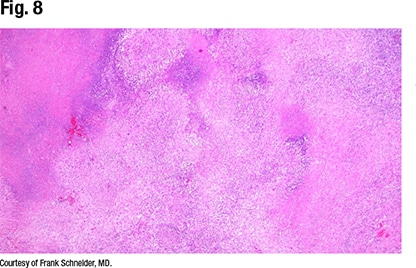

“This is a vessel completely destructed by a necrotizing vasculitis with some granulomatous features, some giant cells, around it. This is a little more necrotizing-looking than a sarcoid biopsy, and sure enough, when you look around, you see the characteristic features of GPA,” Dr. Schneider says (Fig. 8).

Fig. 9 is another occluded vessel, completely surrounded and destructed. Organizing pneumonia is seen, especially in the periphery. “There’s a pure organizing pneumonia variant of GPA, but it’s uncommon. But surrounding these masses you often have a lot of organizing pneumonia, and you have to be aware of that if you see a giant cell, maybe a little bit of vasculitis, and get a core biopsy maybe just from the periphery of a lesion like this,” Dr. Schneider says.

Features of GPA are seen in Fig. 9, so it can be diagnosed as GPA, which Dr. Schneider says he does. “I sometimes describe it as necrotizing vasculitis with parenchymal geographic necrosis and neutrophilic microabscesses and giant cells consistent with GPA . . . though it doesn’t really matter how you describe it. But sometimes, what I find a little disturbing, I see those features and there is no ANCA. If there was no ANCA testing, I don’t know how that changes the post-test probability, but if there was an ANCA test and it was negative,” that raises the question: Can GPA be diagnosed in a patient without ANCA?

Features of GPA are seen in Fig. 9, so it can be diagnosed as GPA, which Dr. Schneider says he does. “I sometimes describe it as necrotizing vasculitis with parenchymal geographic necrosis and neutrophilic microabscesses and giant cells consistent with GPA . . . though it doesn’t really matter how you describe it. But sometimes, what I find a little disturbing, I see those features and there is no ANCA. If there was no ANCA testing, I don’t know how that changes the post-test probability, but if there was an ANCA test and it was negative,” that raises the question: Can GPA be diagnosed in a patient without ANCA?

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management