Karen Lusky

July 2022—Gut pathogens, their histologic features, and a GI pathology and microbiology team approach to diagnosis were the focus of a CAP21 session, “What’s Bugging the Gut?”

Maryam Zenali, MD, Alina Iuga, MD, and Christina Wojewoda, MD, presented a series of cases and highlighted the features, the differential diagnoses, and the integrated workups. Three of their cases follow here, with others to be reported in an upcoming issue.

The patient in the first case is a 14-year-old boy who presented with fever, bloody diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Endoscopic evaluation revealed mucosal edema of the right colon extending to the ileocecal valve and scattered ileocecal ulcers. Due to the severity of symptomatology, a laparotomy was performed shortly thereafter.

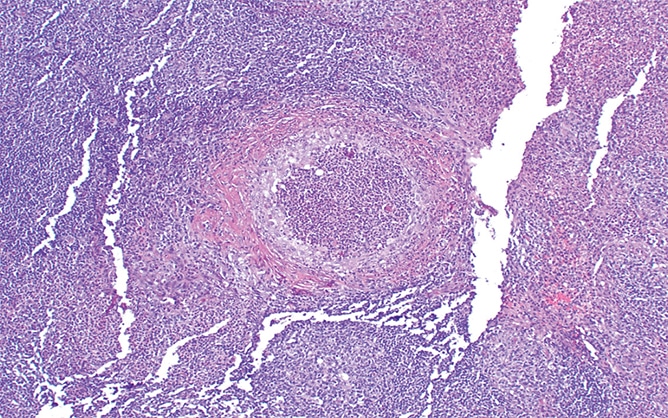

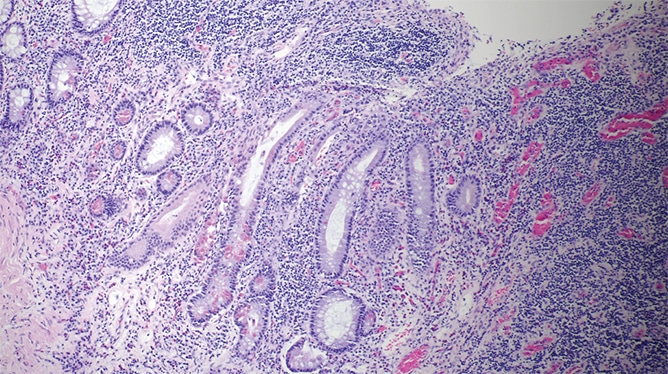

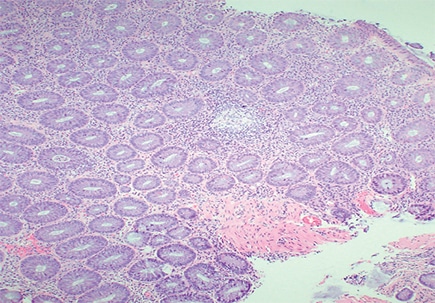

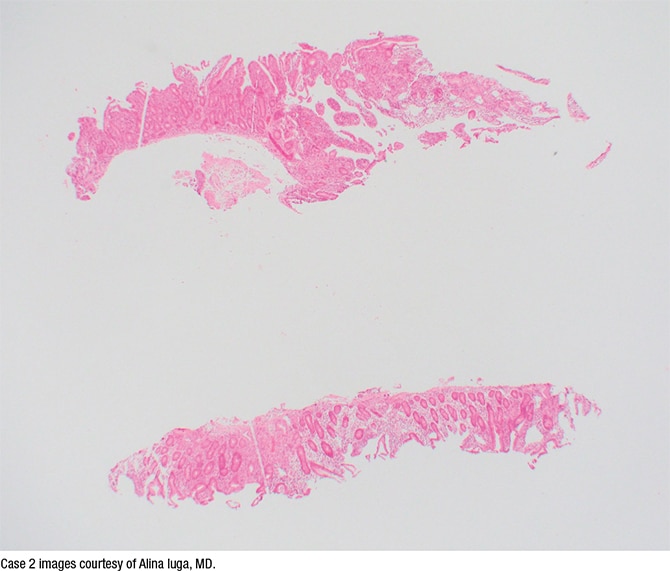

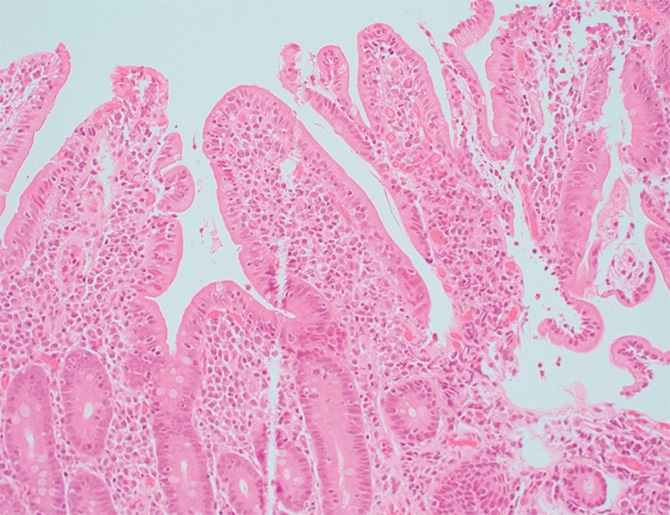

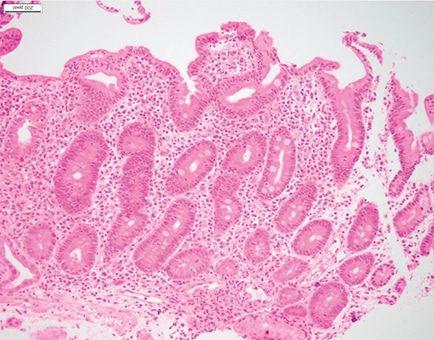

The resection specimen contained suppurative granulomatous appendicitis and active chronic enterocolitis (Figs. 1–3). Granulomatous inflammation was also noted in the endoscopic biopsies of the right colon (Fig. 4), explained Dr. Zenali, assistant professor of pathology, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, UConn Health.

“The differential diagnoses include infectious disease such as Yersinia, salmonella, or mycobacteria enterocolitis and Crohn’s disease,” she said.

This is where the microbiology laboratory can be of help, said Dr. Wojewoda, director of microbiology at the University of Vermont Medical Center and associate professor, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine. If the patient had submitted a stool culture before returning for further surgery, she said, they could have diagnosed Yersinia enterocolitica. “Ideally we would incubate the stool at 25 degrees [Celsius] because Yersinia likes to grow at cooler temperatures.” Not every laboratory will automatically culture for Yersinia enterocolitica, “so this is where the pathologist can interact with the GI clinician or surgeon to ensure we know what we are supposed to be looking for.”

If they were to culture for Yersinia, Dr. Wojewoda said, they would look for lactose-negative colonies on the MacConkey agar. “There is a selective and differential agar for Yersinia enterocolitica called CIN agar,” on which red bull’s-eye colonies form. It can take about 48 hours to grow, and then two to 24 hours to identify the organism. PCR studies on stool are available for Yersinia enterocolitica, “although these are usually incorporated into large multiplex panels, which usually are overkill,” she said, “unless you are looking for something rare.”

Yersinia enterocolitica is a Gram-negative rod in the order Enterobacterales (previously Enterobacteriaceae). Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis can be found in meats (most commonly pork), dairy products, and water. The CDC estimates it causes almost 117,000 illnesses, 640 hospitalizations, and 35 deaths in the U.S. yearly, with children infected more often than adults.

Fig. 1. Appendix H&E 40×

Yersiniosis often involves the terminal ileum/ileocecal region and mesenteric lymph nodes; it may also affect the appendix. Suppurative and granulomatous patterns are common in Yersinia enterocolitica and in particular in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, Dr. Zenali said. “Patients can have concurrent mesenteric lymphadenitis. The organism accesses the bowel wall through the microfold [M] cells of the Peyer’s patches, so the inflammatory reaction often initiates from the terminal ileum and ileocecal valve and can further spread to the right colon.”

In immunocompromised patients Yersinia is a severe disease, as it is in patients with iron overload. “We don’t know the exact mechanism for that,” Dr. Zenali said of overload, but “we know the organism needs iron for growth, and its growth is hindered when iron is scant.”

The histology, although suggestive, is not entirely specific for Yersinia infection, and culture and/or PCR are the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

“Mycobacteria would have caseating granulomas, and you can identify acid-fast bacterium in some of the cases, if not all,” Dr. Zenali said. Mycobacteria also favor the ileocecal valve region, as does salmonella. With salmonella, small, loose to well-formed granulomas, with neutrophilic microabscess, can be seen.

Similar to inflammatory bowel disease/Crohn’s disease, chronic bacterial infection can lead to mucosal architectural distortion. With Crohn’s disease, confluent granulomas are less likely and perianal disease or fistula more common.

Fig. 2. Appendix H&E 100×

Most cases of Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis are self-limited. If treatment is needed, supportive care might be sufficient. Antibiotics are prescribed for those with more severe disease or intractable symptoms. Severe disease may lead to intestinal perforation.

Fig. 3. Resected bowel H&E 100×

Studies report identification of Yersinia by PCR in the normal colon of asymptomatic patients and also in patients with Crohn’s disease. “So the question is what is the bacterial load,” Dr. Zenali said. “We also have to interpret the results in the context of the clinical presentation.”

Fig. 4. Right colon biopsy H&E 40×

Seen in Fig. 7 is active inflammation consisting of neutrophils in lamina propria and focally in the epithelium. “Active inflammation may be seen in celiac disease as a marker of active disease, in particular in pediatric cases,” said Dr. Iuga, director of gastrointestinal pathology and associate professor, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Medicine. “However, when we see it, we should keep in mind the differential diagnosis that includes peptic injury, a drug effect such as NSAIDs, infectious etiology, and even inflammatory bowel disease.”

Fig. 5. H&E stain, 2×

In Fig. 8 small basophilic bodies are seen on the luminal surface of the enterocytes, and thus the differential diagnosis includes infectious parasitic organisms such as Cyclospora cayetanensis, Cystoisospora (Isospora) belli, Cryptosporidium, and Microsporidium. “The first three are members of Coccidia, which is a subclass of microscopic spore-forming, single-celled, obligate intracellular parasites that can infect epithelial cells lining the digestive tract of humans and animals,” Dr. Iuga explained. On histology, they are usually distinguished by size and location. Cryptosporidium (4–6 µm) is usually located at the luminal surface of the enterocytes. Cystoisospora is larger, averaging 20 to 30 µm in size, and Cyclospora measures 8 to 10 µm. They are usually observed inside the enterocytes. “Microsporidia, which average 1.5 to 2 µm, were formerly considered spore-forming protozoa and have been reclassified as intracellular fungi.”

Fig. 6. H&E stain, 20×

In Fig. 9 is a Giemsa stain highlighting the organisms. “Based on the morphologic appearance and the location at the surface of the enterocytes, these are compatible with Cryptosporidium,” Dr. Iuga said.

Here, too, the clinical laboratory can be of help, Dr. Wojewoda added. “If this patient had submitted a stool sample, immunofluorescent microscopy could have been performed. We can do an antigen assay for Cryptosporidium or PCR.”

Fig. 7. H&E stain, 20×

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management