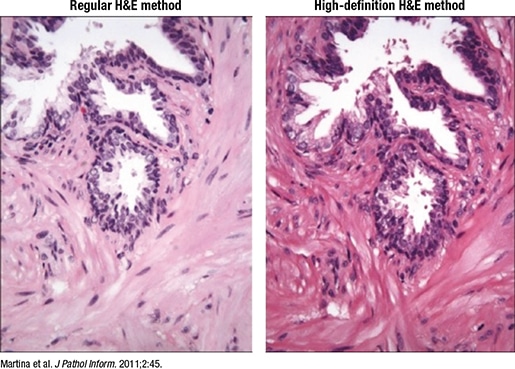

Fig. 3. High-definition H&E

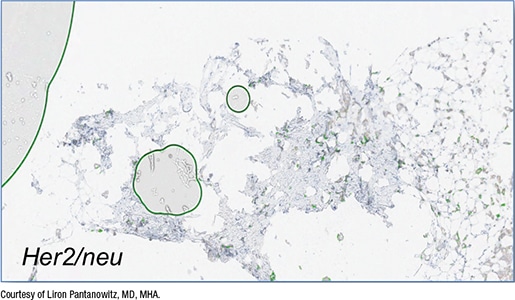

Fig. 4. False-positive QIA

Orienting the tissue on the slide the way it will be viewed digitally is preferable to using software tools that rotate the image after scanning. “It makes for a better end user experience,” he said. Tissue samples should be placed close together for minimal white space and away from the edge, and skin epidermis should be placed on top. Another consideration: “If you’re doing immunohistochemistry work and there are tissue controls, think about how the tissue controls are placed on the slide.” If the controls are on one side, with tissue on the opposite end, “all you’re doing is scanning a lot of white space in between those controls.”

Section thickness should be consistent, he said, and ideally around 4 to 5 microns. Thick sections can affect image resolution quality, and varying section thickness can affect image analysis, with thick sections increasing stain intensity and thin sections causing greater stain variability.

- H&E, special stains, and IHC should be of the highest quality. One option is to use a “digital quality” or high-definition H&E (Martina JD, et al. J Pathol Inform. 2011;2:45), he said, which enhances the contrast “so you can see beautiful cellular detail, and when you do that, you end up with awesome whole slide images” (Fig. 3).

Low-quality coverslipping with overhanging edges can cause the slides or even the robotics inside the scanner to break, he said. “You need the coverslips to be appropriately placed,” and completely dry before scanning. For primary diagnosis, when all slides must be scanned, “you can’t load wet slides into the scanner because that sticky mounting medium over time can cause havoc. So you may need to dry your slides.” One option is to heat them in an oven at 55° to 60°C before scanning. They also should be free of bubbles, dirt, and other defects.

In Fig. 4 is a core needle biopsy of an invasive breast carcinoma stained with HER2 but with bubbles, which the image algorithm read incorrectly as positive membranous staining for HER2. In fact, the breast cancer infiltrating the core did not stain strongly with HER2, Dr. Pantanowitz said. “Yet the algorithm falsely read this as HER2 3+ because of the air bubbles being counted as having membranous staining.”

Excess mounting medium should be avoided “because that can leak and end up on top of the coverslip.” Though it may not be a problem in an automated histology lab, “this is a problem if you’re making slides by hand in a small operation, or you’re using frozen section slides that you may need to scan at the time of intraoperative consultation or later when you get back to the histology lab and scan them into the case.” Excess mounting medium can cause the image to be out of focus or affect the mechanics inside the scanner.

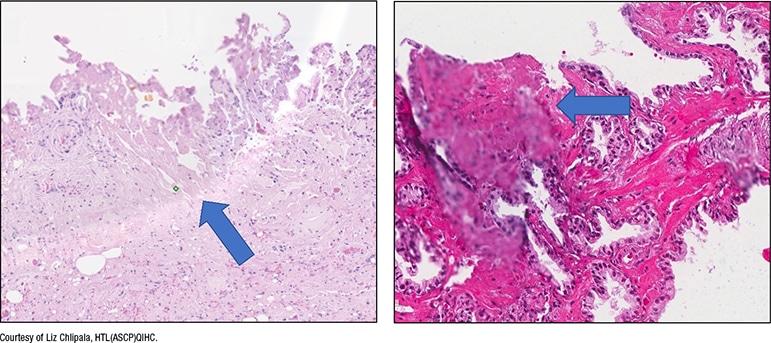

In Fig. 5 is a slide with excess mounting medium. In the digital image (right), “there’s mounting medium on the coverslip and the area’s slightly out of focus.”

Unlike glass coverslips, film and tape do not require mounting medium and dry quickly. The tape sticks to the slide via a chemical reaction, Dr. Pantanowitz said, and the slides can be scanned immediately. But plastic is more easily damaged than glass, so the slides may get scratched when being removed from or returned to the slide archive. “And if someone is dotting or marking your slides and you want to then clean them with alcohol, you may damage the plastic.” Some have reported that if the tape isn’t high quality, or if the taping isn’t done well, it can peel. Warping over time is of less concern with today’s technology, he said.

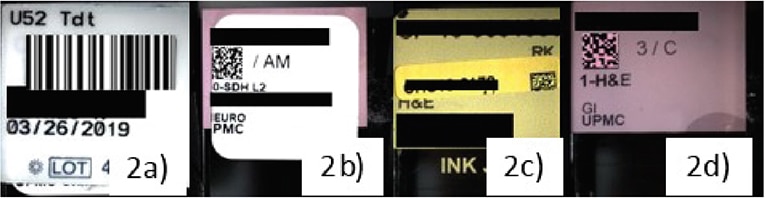

Slide labeling, Dr. Pantanowitz said, is the “Achilles’ heel” of digital pathology. Imperfect barcodes are a frequent cause of scanning failure (Fig. 6). “Linear barcodes tend to get damaged more easily, and they can be stretched, so they’re not as robust as 2D barcodes.” And because the barcode readers on some scanners are overly sensitive, it’s critical to ensure that the labels do not overhang the slides and that they aren’t covered in wax or other debris. Label printer maintenance should be performed regularly, he said, lest the printer “be the cause of a failed digital pathology operation.”

Consult slides also pose challenges. “Foreign slides come with their own set of problems, including their own barcodes,” he said. Multiple barcodes on one slide can confuse the scanner barcode reader. “Putting your own barcode on is recommended so that it links the newly accessioned case to your lab information system, and that may require double labeling, or a piggyback label to cover the outside foreign label.” And because pathologists want to be able to read the foreign label, one solution is to place a new label with a transparent top and its own barcode over the outside label. The clear portion obscures the foreign barcode so it isn’t read by the scanner, he said, but a pathologist can still review the consult slide details. And the slide then can be returned without damaging the client’s original label. “There are vendors who supply such labels to deal with consult slides.”

Fig. 5. Excess mounting medium

In a manual workflow, the quality check (QC) for slides is completed in the histology lab. “What happens in the digital system?” The question, he said, is whether the QC work should be done before or after scanning. “Everyone has a different solution, and some people have no solution,” he said. If the QC is completed before scanning, that involves having someone check each slide. “It’s manual, and it’s highly subjective and laborious,” and isn’t feasible for an operation in which all slides are scanned. “It actually goes against trying to automate this process.”

Fig. 6. Barcode-related scan failures

a. Scanners that read only 2D codes result in failure to read 1D barcodes. b. 2D labels printed out of alignment resulted in scanner failures. c. Misaligned added labels for consultation cases cause scan failures. d. Etched labels were found to be the most successful.

Dietz R, O’Leary M, Duboy J, Piccoli A, Hartman D, Pantanowitz L: Using Microsoft Power BI for real-time analysis of a distributed whole slide scanning operation, Pathology Visions Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, 2019. Published in Journal of Pathology Informatics, 11, 1, S36-S37, 2020.

Another option is to QC slides post-scan, and have technologists pan only select digital slides at low magnification to assess for imaging artifacts. “There are some labs doing that, but it still takes time and they don’t look at everything.” Or slides can be sent to the pathologist without any QC, and if the pathologist finds an area of concern, they can request a rescan. Artificial intelligence tools that can perform this QC work are being developed, he said. Thus far, researchers have reported developing machine learning tools that can detect blur factor in images, create heatmaps that show where slides may be out of focus, detect tissue folds, perform stain normalization and correction, and even create “fake” sections. HistoQC, an open-source QC tool, is one tool that has gained popularity (available on Github—go to github.com/choosehappy/histoQC).

The CAP and the National Society for Histotechnology offer HistoQIP, in which an expert panel of histotechnologists and pathologists evaluate submitted slides for histology and scanning technique plus quality using grading criteria. Dr. Pantanowitz’s laboratory is a new enrollee. Their experience so far: “Scoring is quite harsh, but it has allowed us to improve the quality of our slides,” which he calls “perfect for a good, successful digital pathology operation.”

“AI developers are looking at using greater heterogeneous data for training models and trying to make sure they accommodate for artifacts. I don’t think it’s possible to do that for every case and every type of artifact,” he said. “So I think it’s time we also started standardizing our preimaging steps.”

Charna Albert is CAP TODAY associate contributing editor.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management